Featuring Visionary Yarn-paintings and Beadwork from Mexico's Sierra Madre

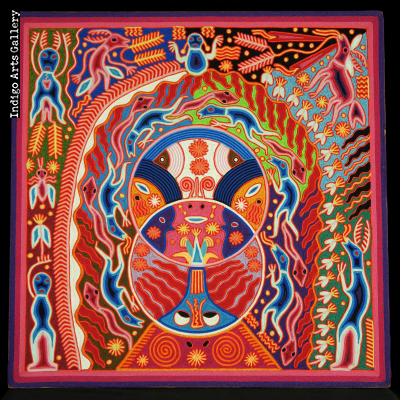

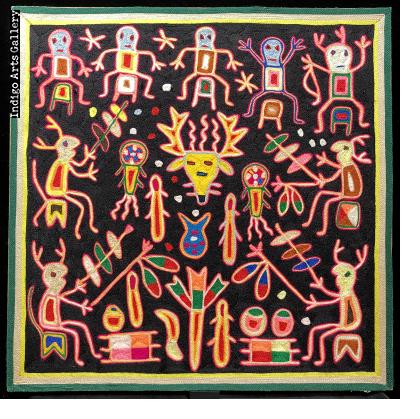

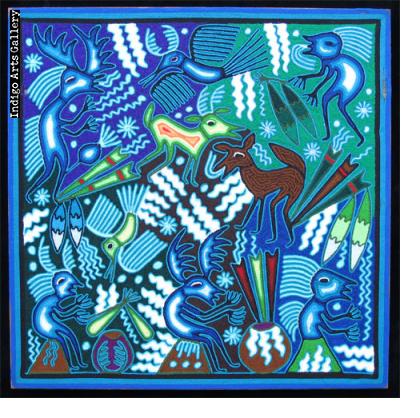

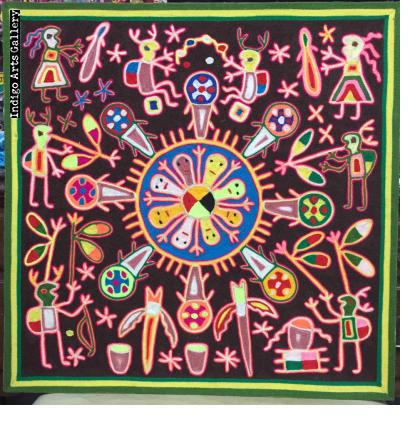

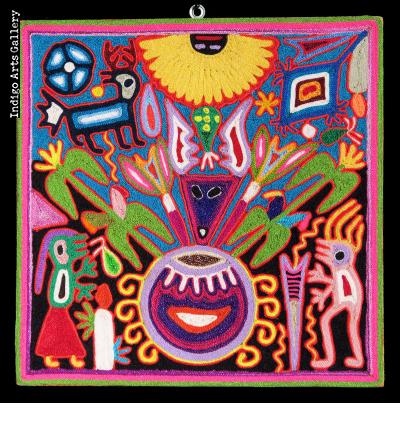

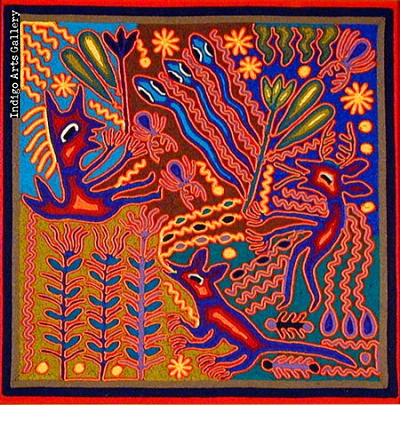

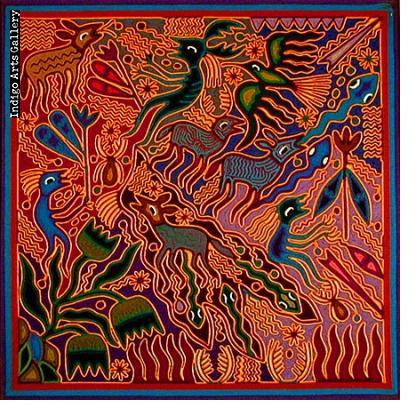

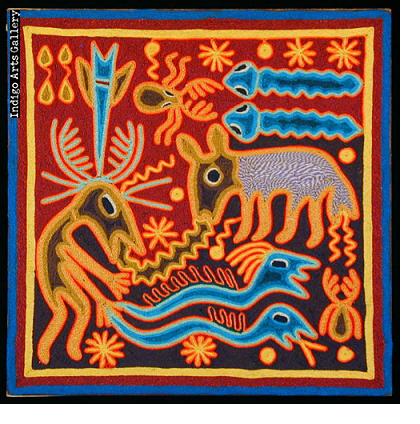

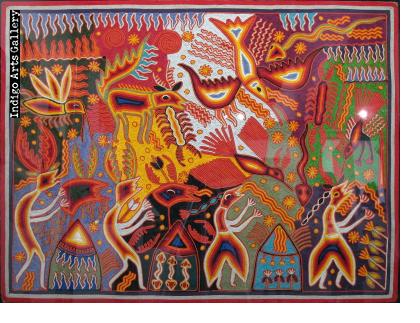

PHILADELPHIA - Visions to Heal the World, which opens at Indigo Arts Gallery on October 7th, 2005 features a collection of visionary artworks from the Huichol Indians of Mexico’s remote Sierra Madre Occidental region. It centers on the nierika yarn paintings by the celebrated shaman/artist, José Benitez Sanchez. Benitez was the subject of Mythic Visions: Yarn Paintings of a Huichol Shaman, the dazzling 2003 exhibit at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The paintings reflect the visions of Huichol shamans - Huichol history and mythology and especially the peyote-inspired visions through which they believe they can communicate with the deities to heal themselves and their world. The exhibition, which also includes yarn paintings and beaded works by several other Huichol artists, continues through November 27th. On October 15th (3 to 5pm) Indigo Arts will host a special lecture and video presentation by Michele Belluomini, who has studied with the Huichol people for nearly twenty years.

Thanks to their isolation in the mountains and canyons of the state of Nayarit, the Huichol, alone among the indigenous peoples of Mexico, were able to largely resist conversion to Christianity by the Spanish conquistadors. They have maintained their pre-conquest religion and traditions nearly intact. The Huichol practice a nature-based religion guided by shamans, which the anthropologist Peter Furst calles “a powerful everyday spirituality that seemed to owe nothing to the religion of the conquistadores.” The religion and the sacred arts which serve it are directed toward communication with a pantheon of “numberless male and female ancestor and nature deities” and in so doing finding the causes and cures of illness. 19th century ethnographer Carl Lumholtz called the Huichol a “nation of doctors”, for an extraordinary number of Huichols (an estimated third of adult men) are mara’akámes or shamans. Furst adds that an even greater number of the Huichol, male and female, are also artists.

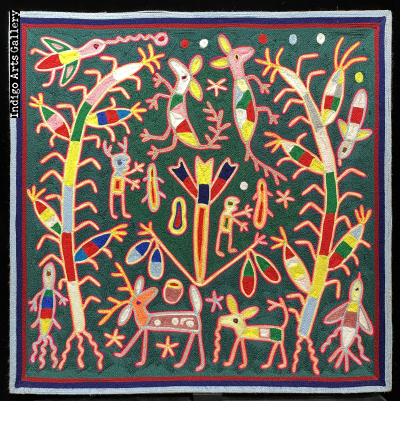

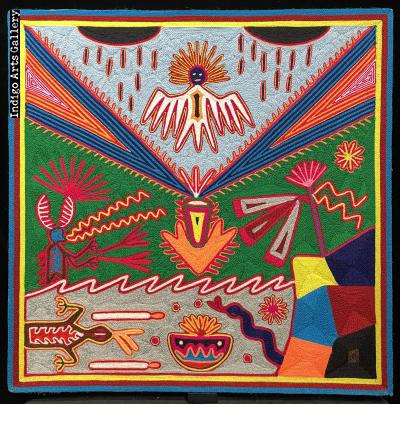

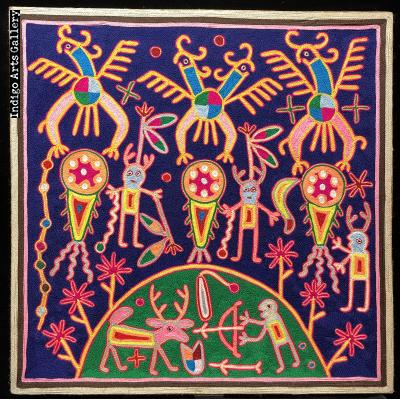

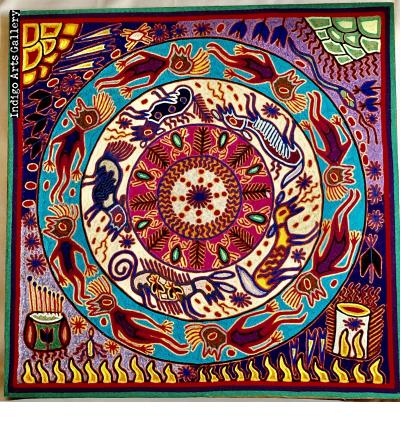

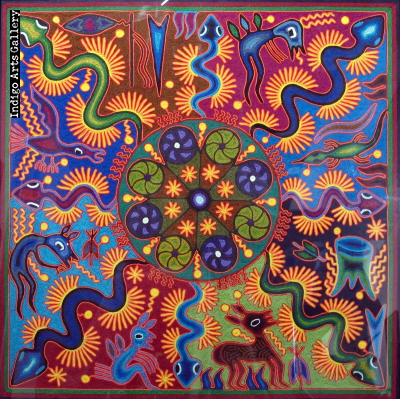

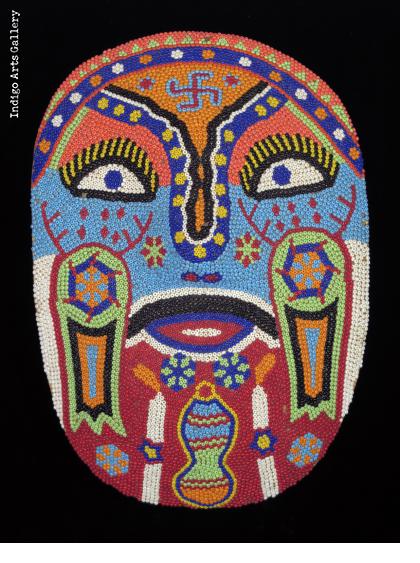

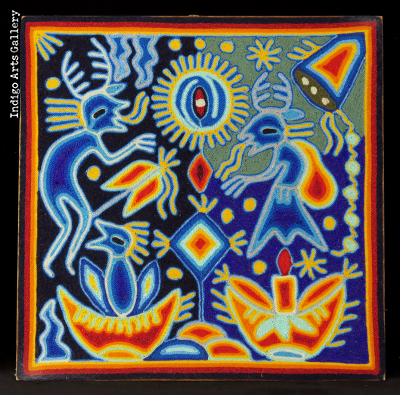

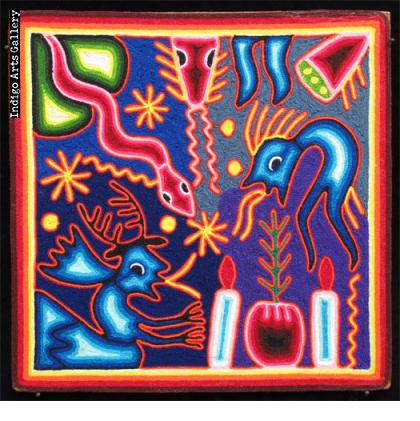

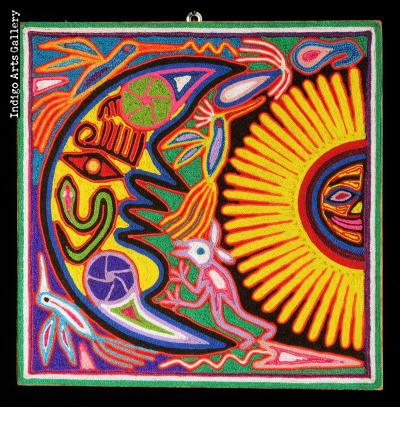

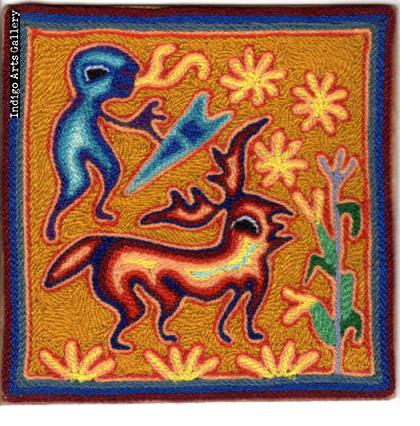

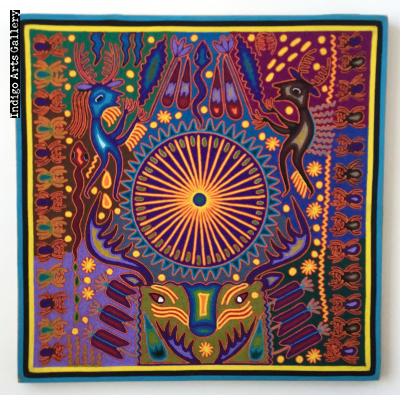

A central aspect of the religious life of the Huichol, and an essential rite of every shaman, is the peyote pilgrimage to Wirikuta, a remote desert region 300 miles away in the state of San Luis Potosi. After the twenty day walk (now sometimes shortened by a ride on a truck or bus) to Wirikuta the Huichol pilgrims “hunt” for the sacred hikuri or peyote cactus. They shoot arrows into the first peyote they find, just like the sacred deer with which it is associated. The pilgrims consume some of the peyote in rituals in Wirikuta, and the rest is brought back for the consumption of the community.

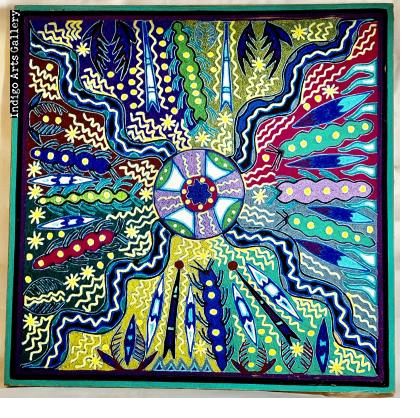

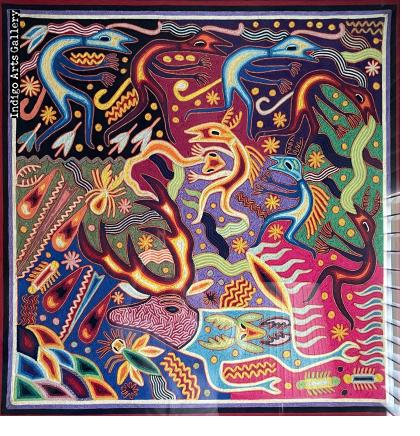

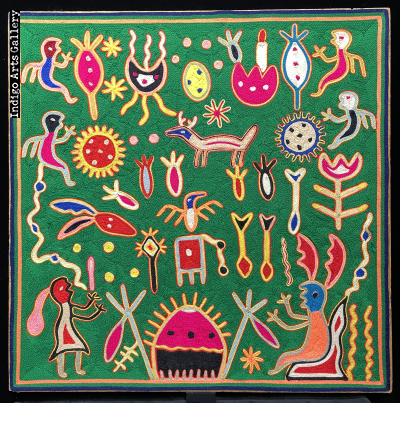

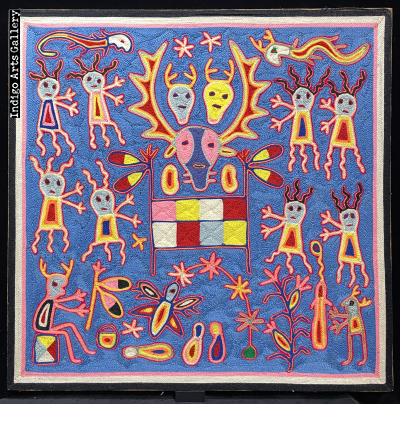

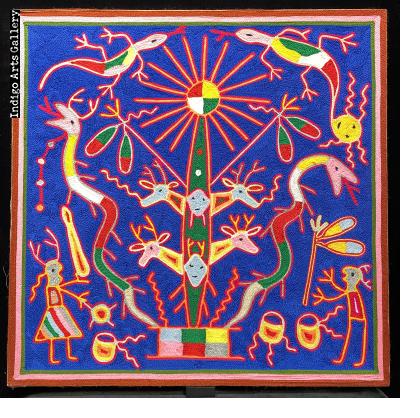

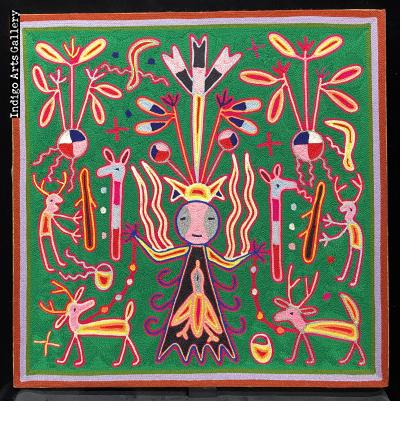

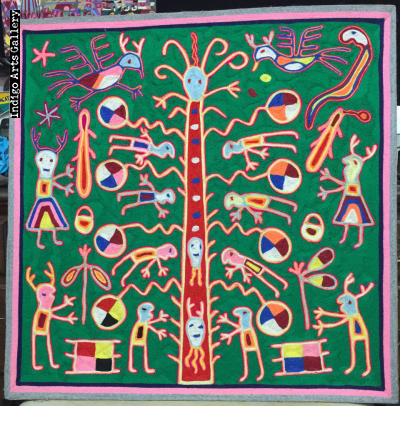

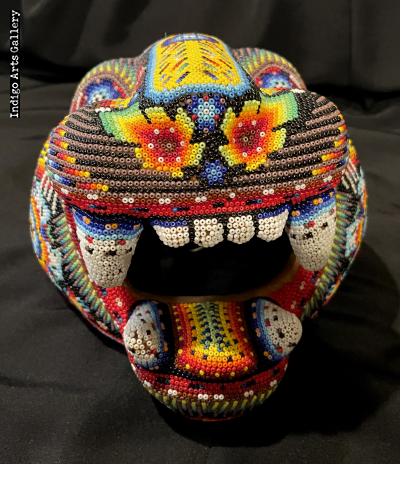

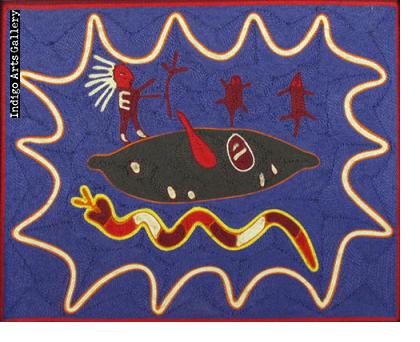

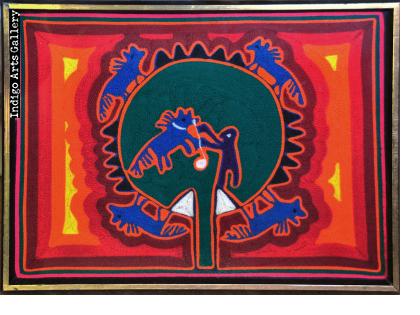

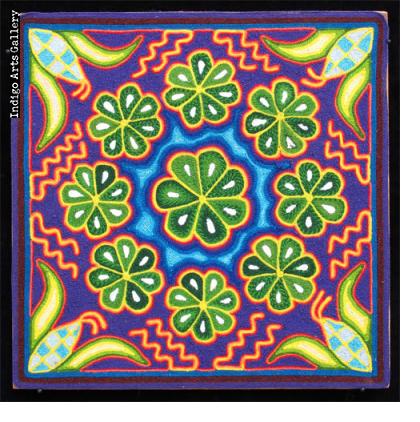

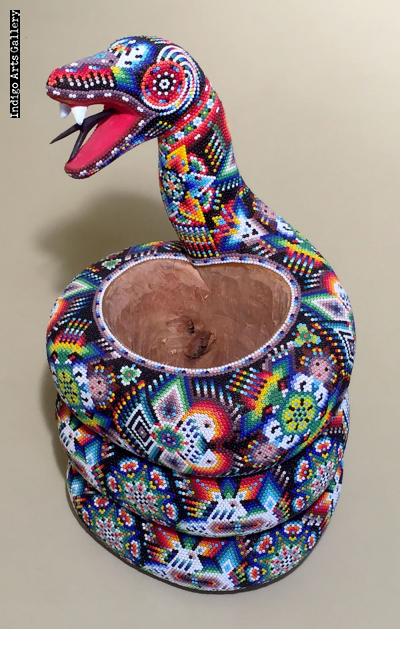

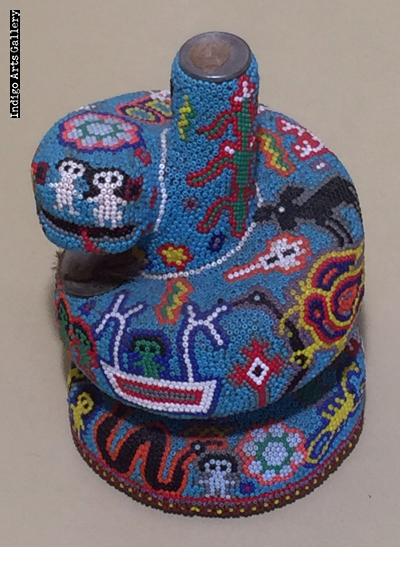

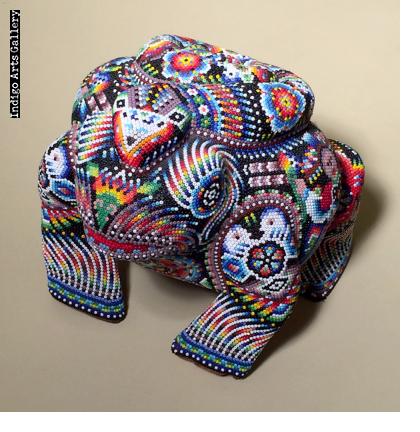

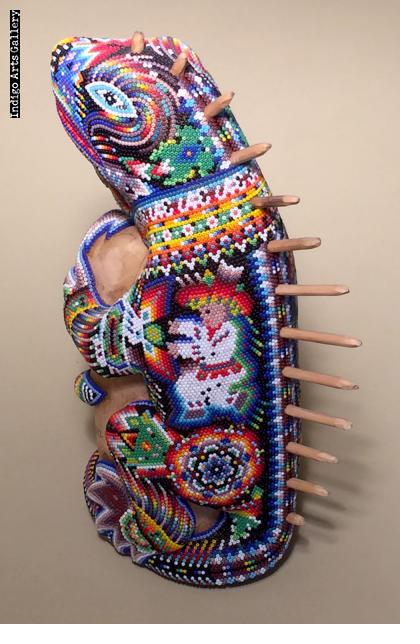

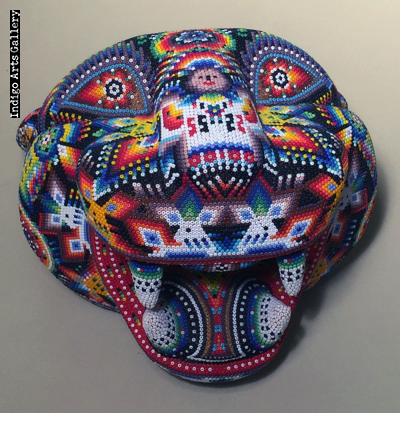

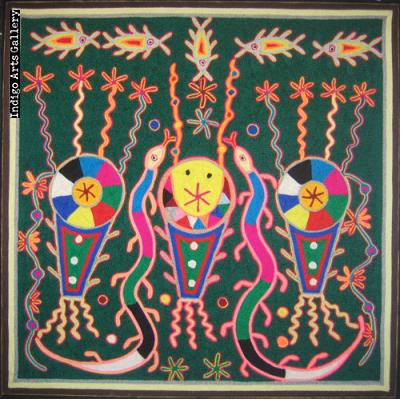

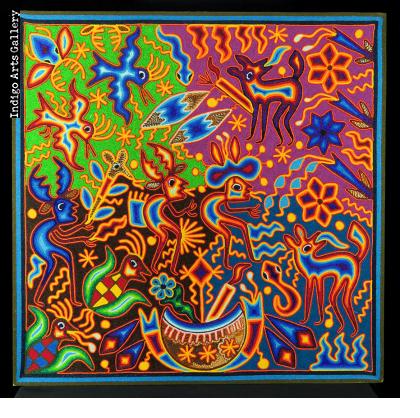

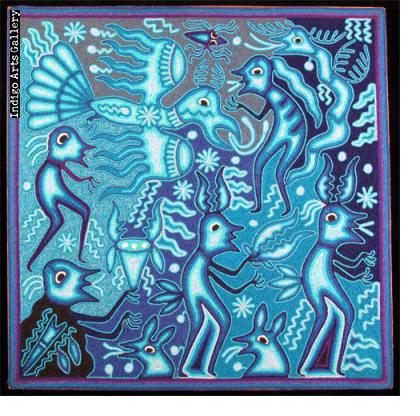

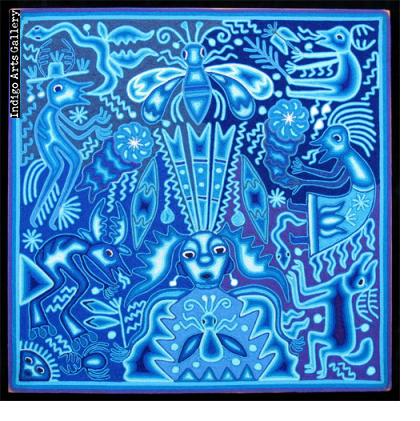

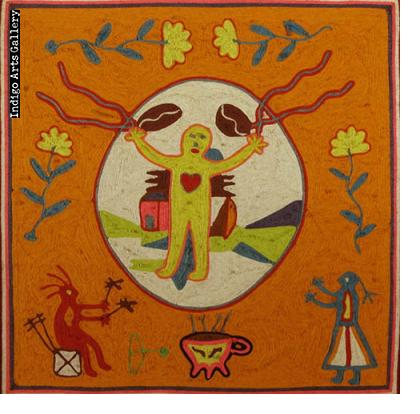

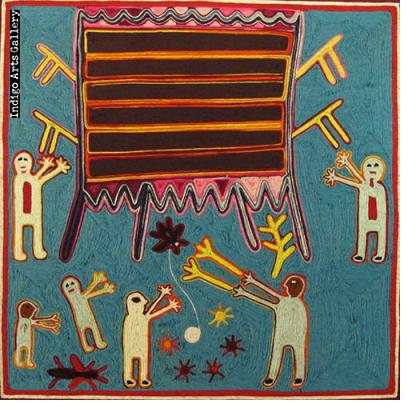

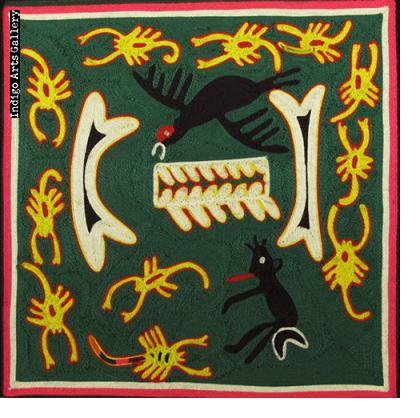

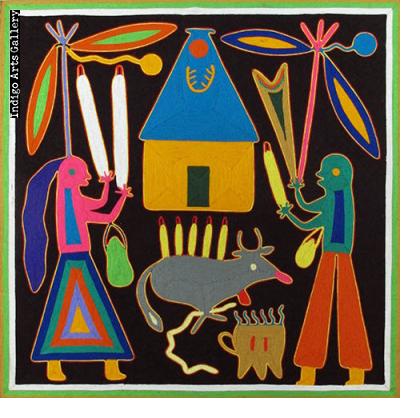

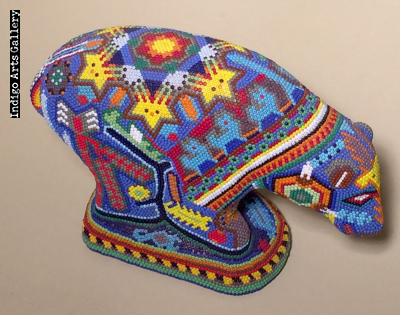

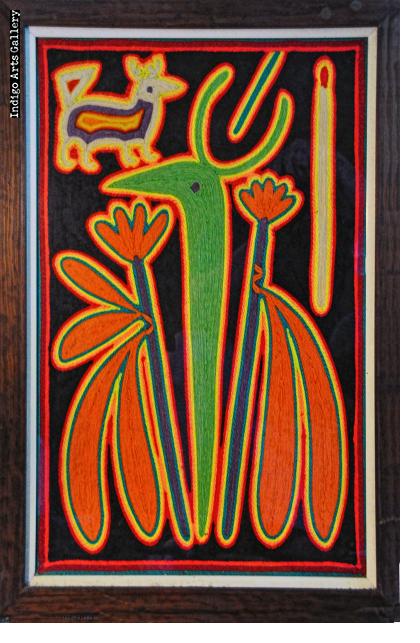

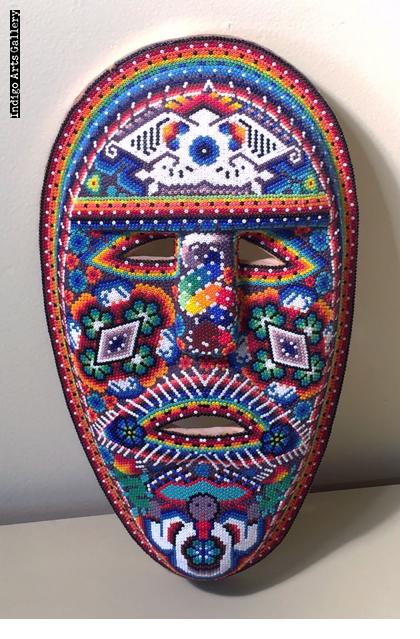

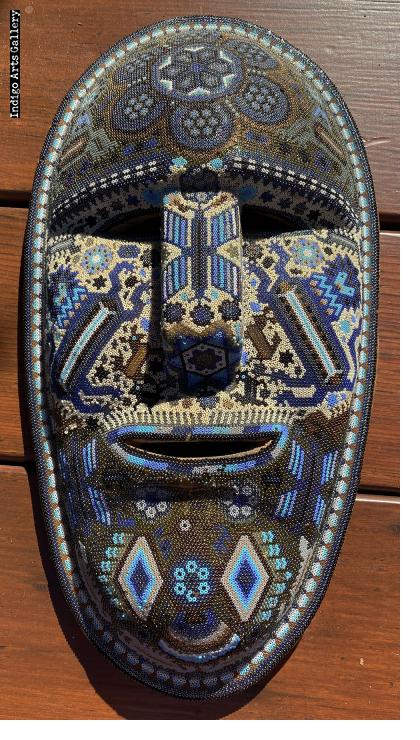

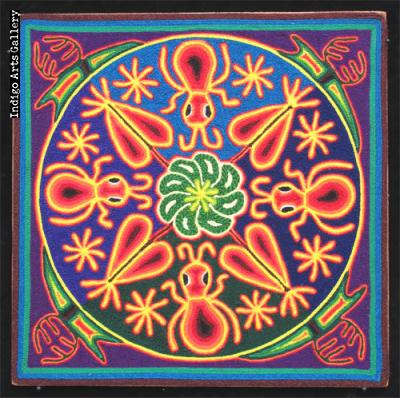

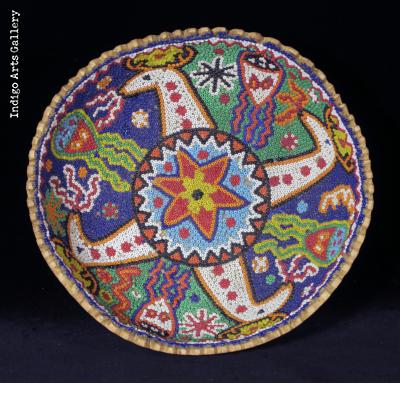

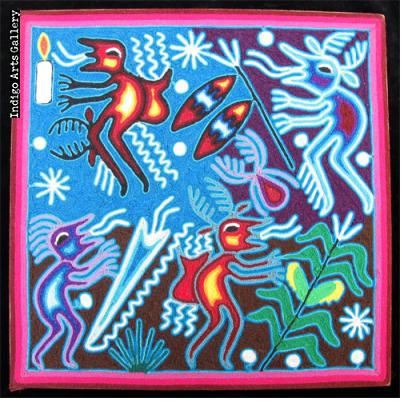

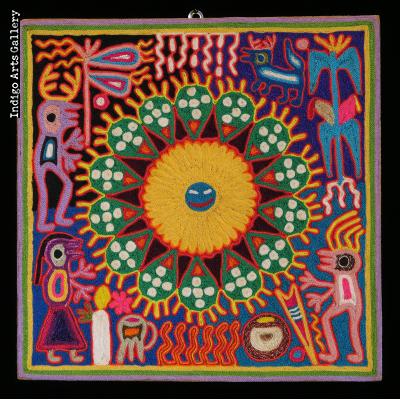

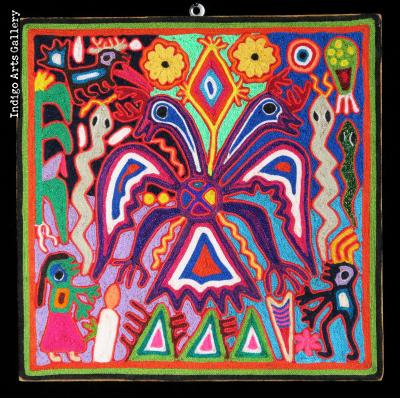

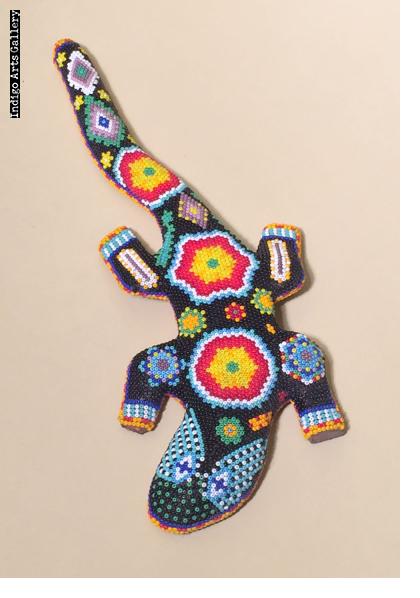

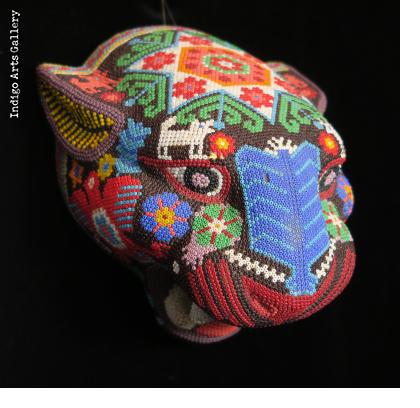

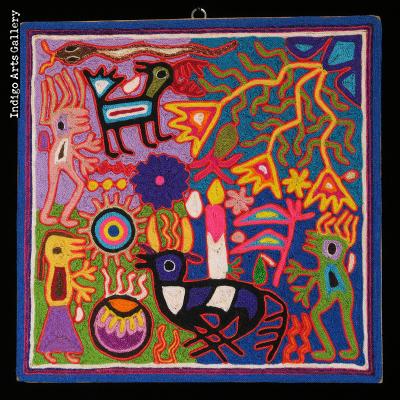

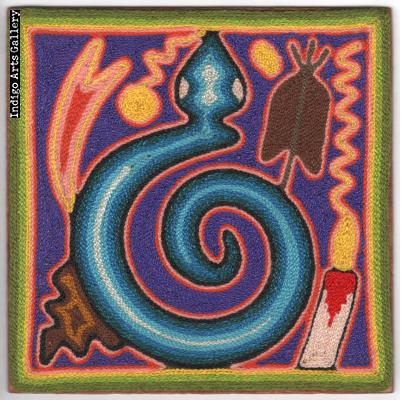

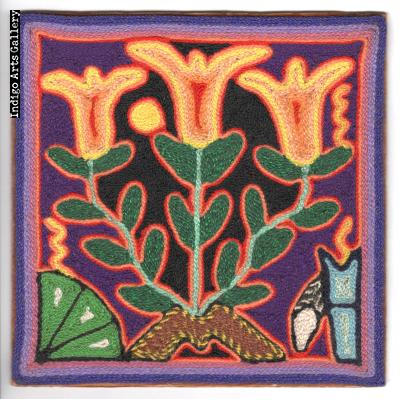

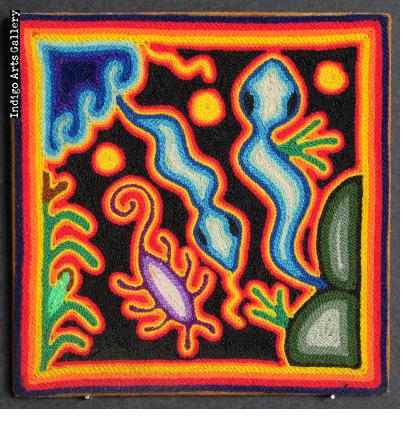

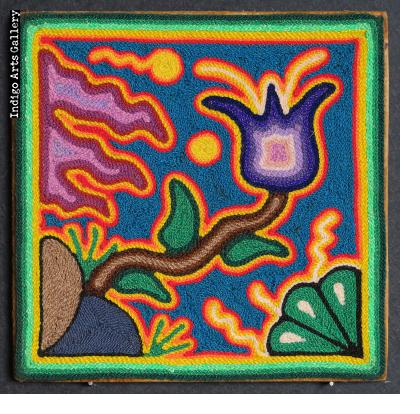

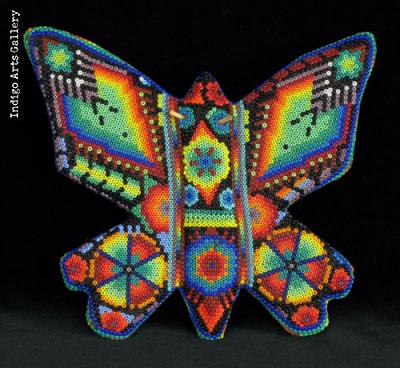

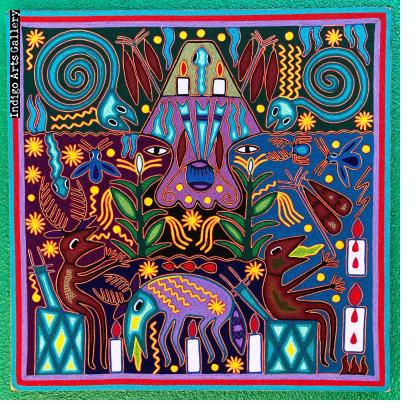

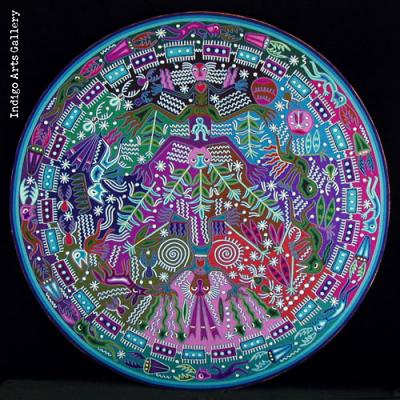

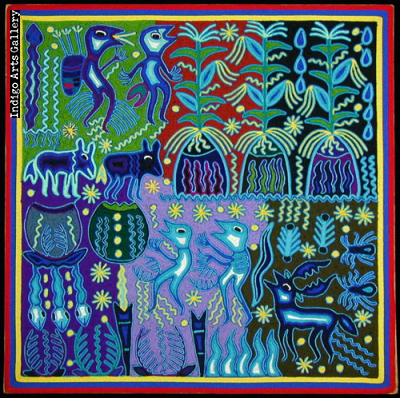

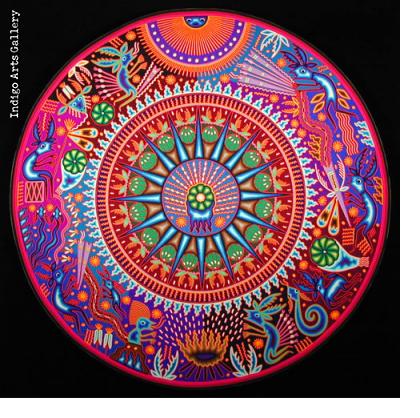

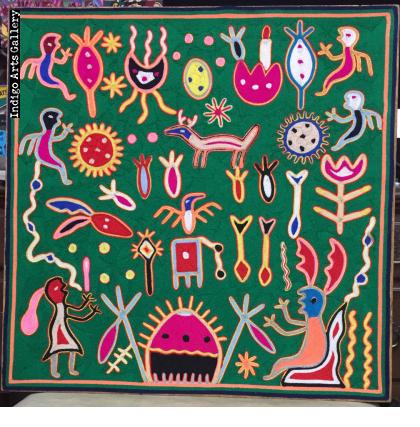

The yarn paintings shown at Indigo Arts are the continuation of a variety of ritual arts long practiced by the Huichol. The Huichol are known for the symbolic patterns of plants and animal spirits, which they lavish on their cross-stitch embroidery, xukuri beaded gourd votive bowls, and a variety of prayer objects and crosses woven of sticks, feathers, yarn and other materials, which they called nierika. What arose in the 1950’s and 1960’s was the application of many of the same rich Huichol iconography and the same materials and skills to a flat surface. To make these paintings the artist spreads beeswax on a board, sketches out a design and fills it out by carefully pressing brightly colored yarns into the wax. The first paintings were largely decorative. Sold in government crafts shops they could bring in some needed income to community. But it was not long before the shaman-artists realized the paintings’ potential to tell the stories and myths of the Huichol, and to record their sacred visions.

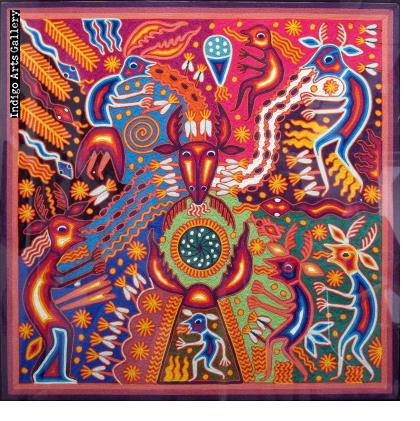

The shaman/artist who pioneered this style in the mid-1960’s was the late Ramon Medina Silva. Using this yarn ”canvas”, Medina told traditional stories of the creation, the peyote/deer hunt, the journey of the soul after death, and the origins of Father Sun and Tatewari, Grandfather fire. Stylistically these early yarn paintings now seem quite primitive, the characters often similar to the stick figures in petroglyphs, in relatively static compositions. The artist who carried this art to its current level was Medina’s cousin and one-time apprentice, José Benitez Sanchez.

José Benitez Sanchez was born in 1938 in the settlement of San Pablo, where his father was a famous mara’akáme. Benitez credits his own path as a shaman to a revelation following an illness when he was fifteen, after which he set off on his first pilgrimage to Wirikuta. Benitez pursued the dual paths of shaman and artist almost from the start, and has been recognized as a master since the 1970’s. He pioneered a style of fluid figures in compositons which are dynamic, complex, and colorful to the point of being psychedelic. His success as an artist coincided with his growing stature in his own community. He helped found the indigenous community of Tsitákua, and was elected its first tatoani, or governor. Benitez’ work has been exhibited world-wide, and is included in many private and public collections. In addition to the substantial collection which was exhibited at the University of Pennsylvania his work is included at the UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

The other artists exhibited at Indigo Arts are Benitez’ students or peers, including two of his wives, Josefina Benitez and Maria de Jesus Rivera Hernandez de la Cruz, his son Eliseo Benitez, and his compadre Maximino Renteria de la Cruz.