About the Artist

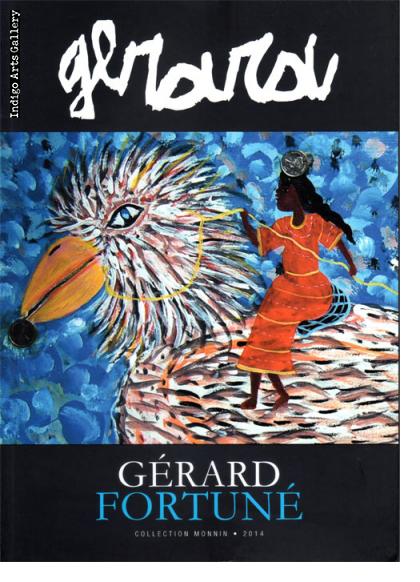

Gerard was born near where he spent the rest of his life, in Montagne Noire, above Petionville, Haiti. The date of his birth is in dispute. One biography lists it at 1933, another firmly at May 2nd, 1925, and his obituary by Le Centre d'Art lists it at 1924. He told me he did not know when he was born. He worked as a pastry chef at a hotel, before beginning to paint in 1978. Gerard’s work has been exhibited internationally, is included in the permanent collections of Ramapo College, New Jersey and the Waterloo Museum of Art in Iowa, and is published in Where Art is Joy (Rodman, 1988), Dialogue du Réel et de L’imaginaire (1990), and Island on Fire (Demme, 1997), and the recent monograph, Gerard Fortuné.

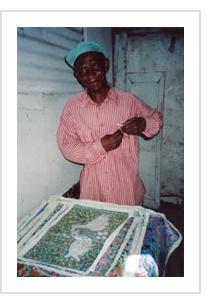

Gerard was profiled in a January 2014 article in Hand/Eye by Rebeca Schiller, with photographs by Maggie Steber, Fortune's Good Fortune: Naif painter Gerard Fortune is obliged to paint:

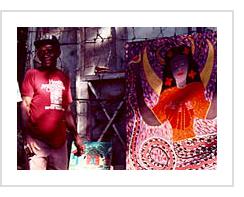

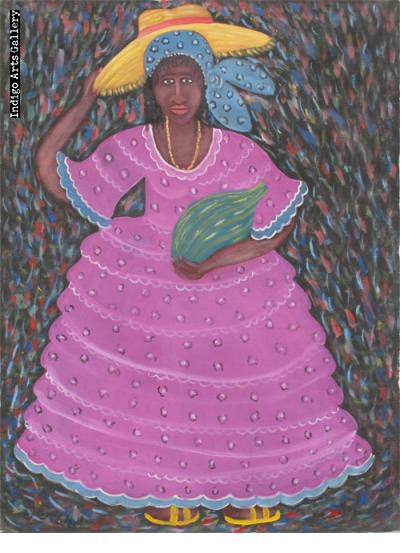

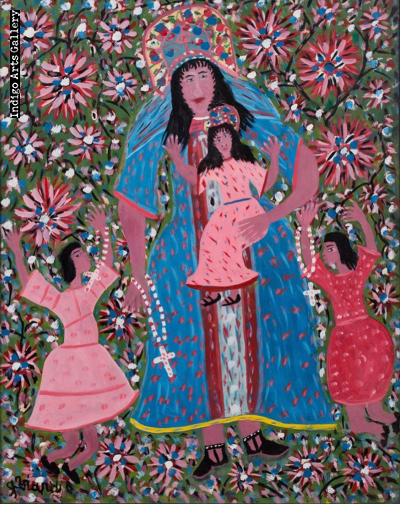

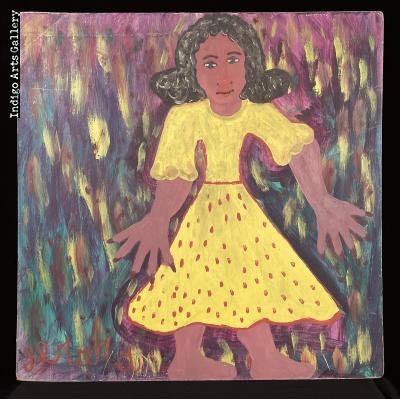

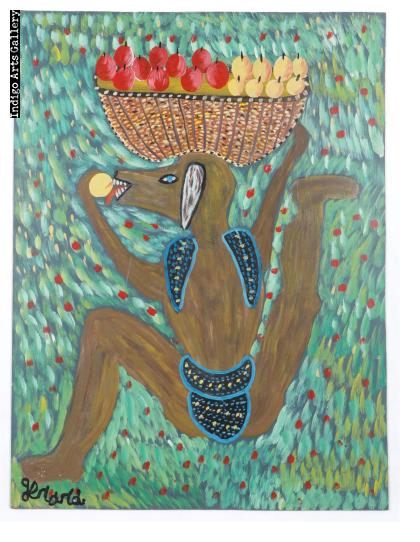

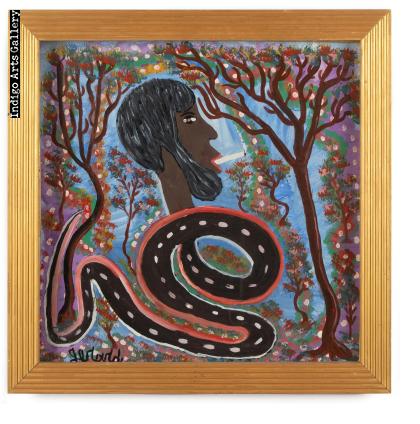

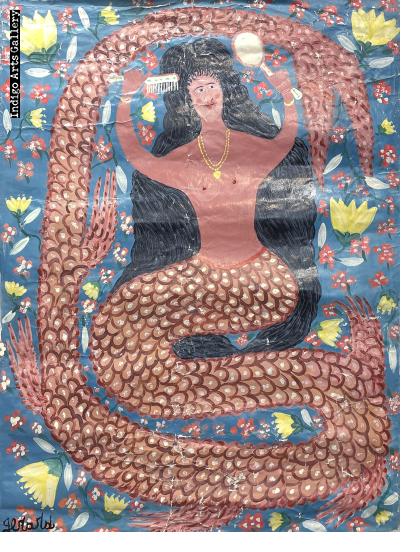

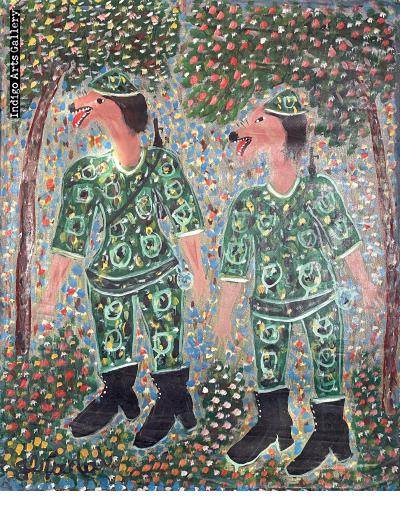

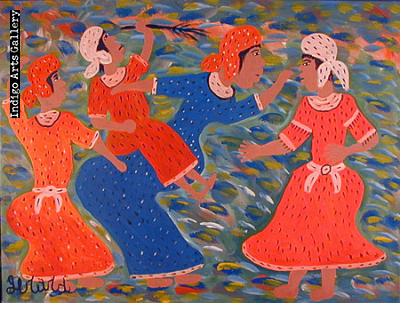

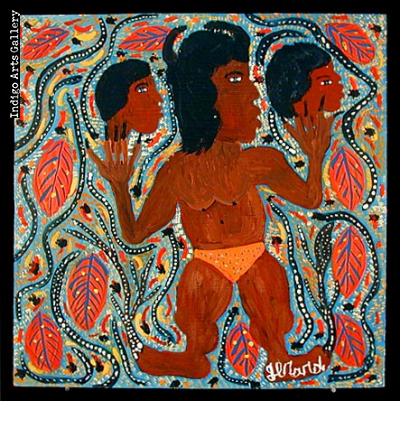

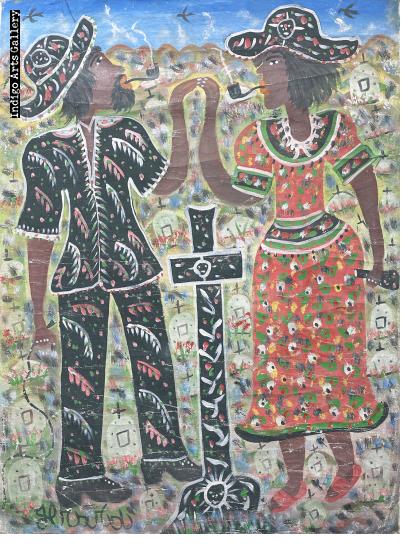

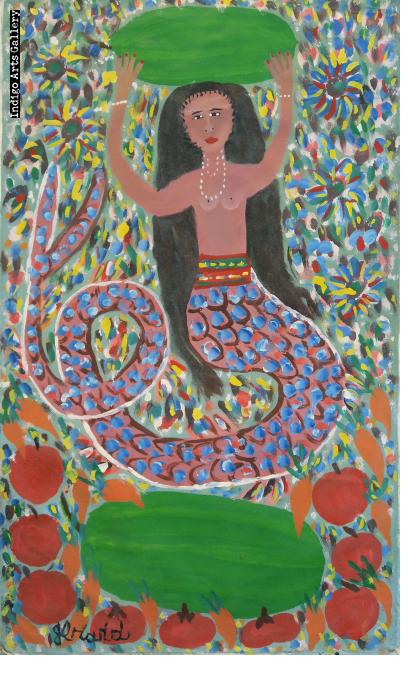

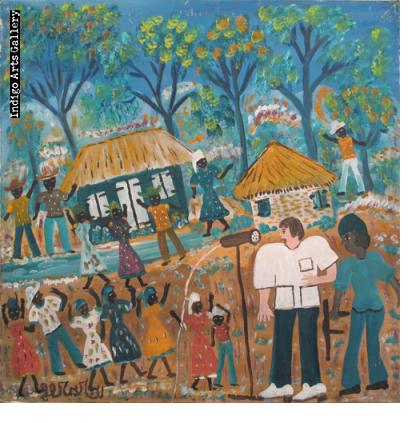

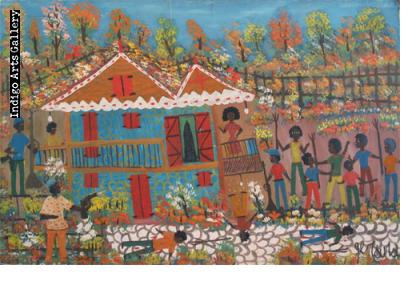

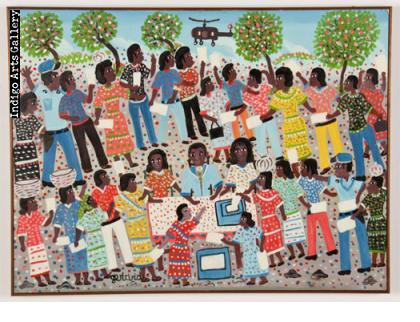

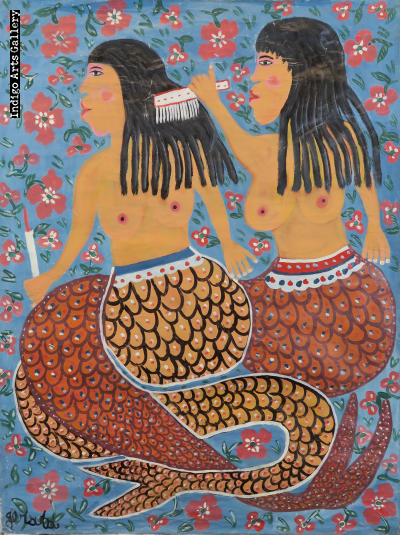

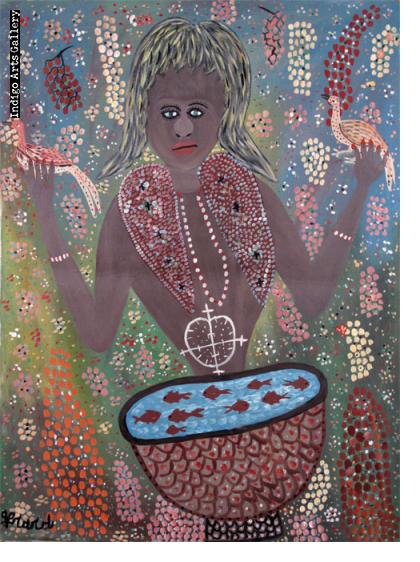

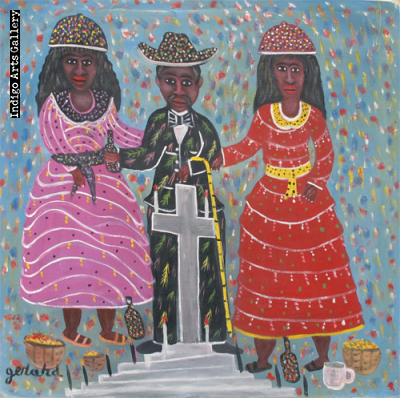

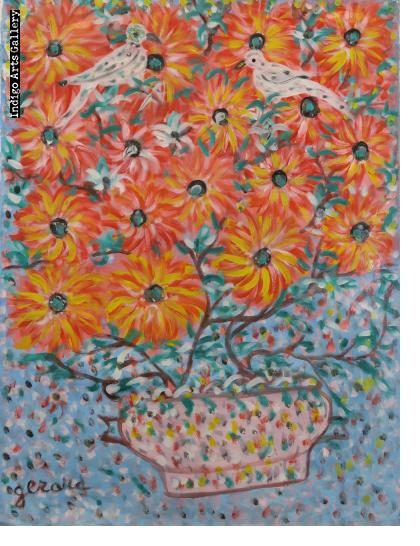

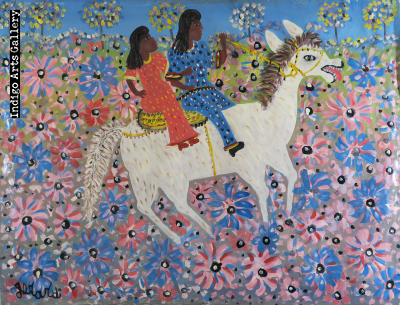

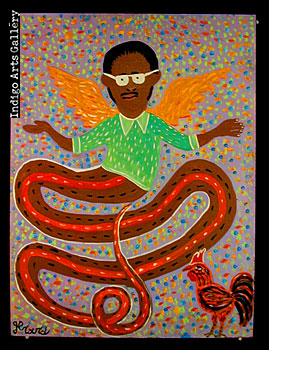

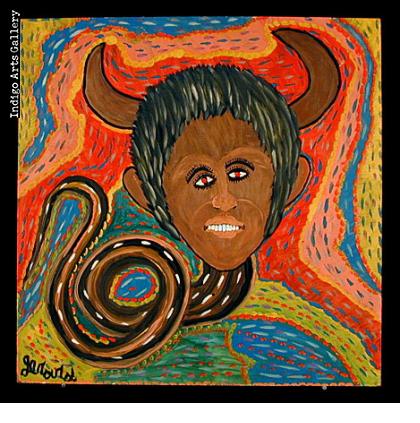

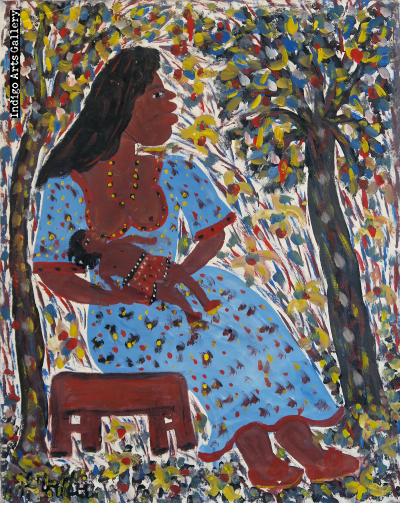

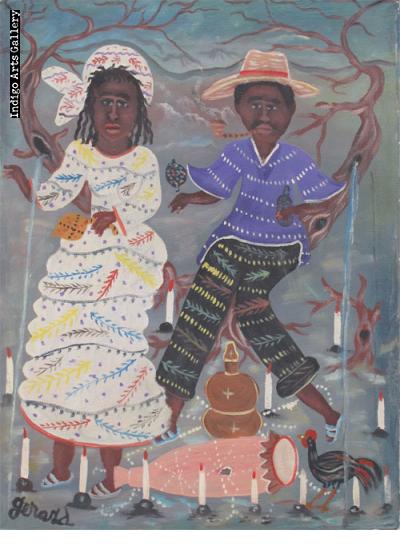

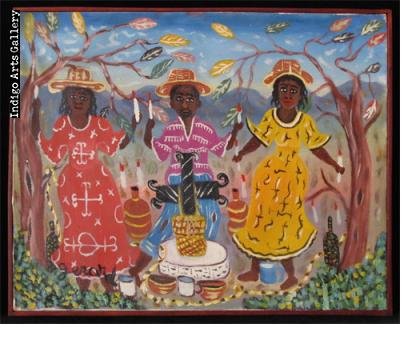

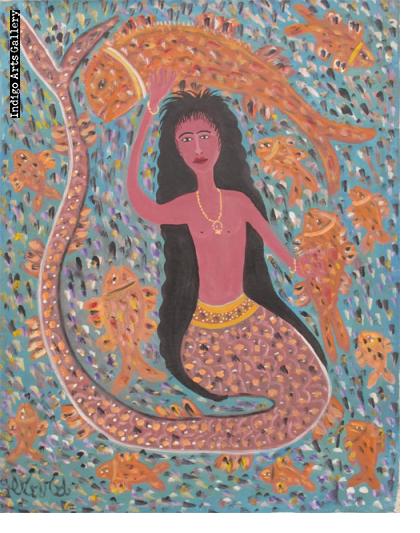

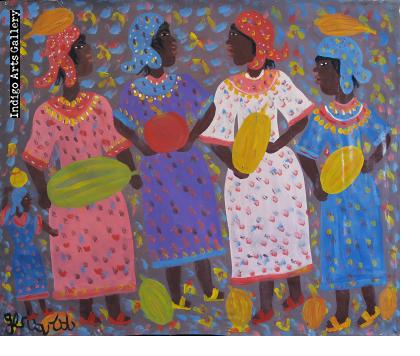

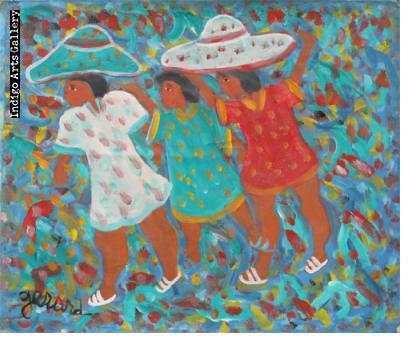

Gerard Fortune paints everything: “I’m obligated to paint vodou and Jesus and flowers and the sea. And villages and anything that comes to mind.” Fortune is one of the most prolific and collectible painters in modern Haiti – recognized by connoisseurs of Haitian art in North American and Europe and respected by his peers at home. His naïf renditions of everything from village scenes to vodou ceremonies to politics line collectors’ walls with bright renditions of daily life, including the aftermath of the January 2010 earthquake that devastated much of Haiti.

Gerard doesn’t know his age. He was born in Petionville, located on the outskirts of Haiti’s capitol. He says he has been alive since former Haitian dictator Jean Claude Duvalier was a child, which would put him between 50 and 60 years old. But his age is less important than what he creates.

Several decades ago Gerard worked in the kitchen of a private home where he saw paintings by both Haitian and international artists. He decided to try it himself. His first painting was an 8x10 inch canvas of Jesus on the cross. A Frenchman liked it and bought it. He continued to sell to the same Frenchman each time he made a new piece, always in a naïf style of painting -- very childlike, using whatever paint he could find, always in bright colors.

The Frenchman encouraged him to continue and at some point, Gerard gained confidence and began taking his work to Issa El-Saieh, a former orchestra leader in Haiti who went on to become one of Haiti’s major gallery owners. It was at Issa’s gallery in Port au Prince that I first saw Gerard’s work. Surrounded by hundreds of paintings hung on walls, piled on tables, standing on the floor, I discovered a huge painting of happy village life. There were pretty little houses, and people of all sizes, dogs fighting over a bone, and cars and trees and flowers and bright colors. It was a painting of Haiti…if Haiti were a place where things were perfect. Later, I found another of Gerard’s village scenes of the same size --and they hang across from each other in my home.

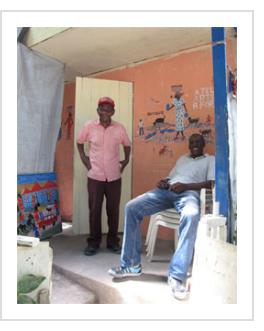

Issa made a contract with Gerard and didn’t want him to sell to other galleries. Well-known dealer Georges Nader, too, took Gerard’s paintings but also wanted to be sole representative. But such arrangements did not (and still don’t) suit Gerard. He likes to be free to do what he wants, in terms of what he paints, how many paintings he makes, and to whom he sells.

“God tells me what to paint, the feeling of each painting.” He says that God gives hope to him. “Inspiration comes from God at all hours, “ he says, and so sometimes he works all night. Anyone can come to see him working by candlelight when there is no electricity in the one-room home that he shares with a small cat.

During the earthquake, he said his tiny house shook. Walls outside toppled over. He ran out into the courtyard. Other family members living around the same courtyard ran out of their small houses as well. No one was hurt and the homes didn’t suffer too much damage. “That’s because I have a good heart. God protects me. It was the first time I saw a goudou goudou (the popular term for earthquake, meaning rumble-rumble) —and I thought it was the end of the world.”

But the world goes on, day by day. And from his Montagne Noir home, Gerard continues to paint scenes of Haitian life in the way of his choosing.

Maggie Steber has worked as a documentary photographer in 60 countries. Her work in Haiti spans 25 years. Steber has received the prestigious Alicia Patterson Foundation Grant and the Ernst Haas Grant as well as many other awards and honors. A collection of her Haiti photographs was published by Aperture as Dancing on Fire: Photographs from Haiti. Her work appears regularly in National Geographic, The New York Times, Smithsonian, The Guardian of London and many other American and European publications.

On December 11, 2019 we received the news that Gerard has passed away. Rest in peace!

You may read the obituary posted by Le Centre d'Art here.