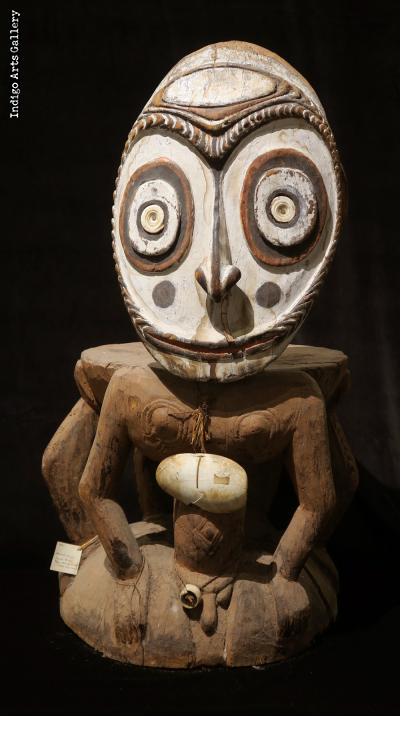

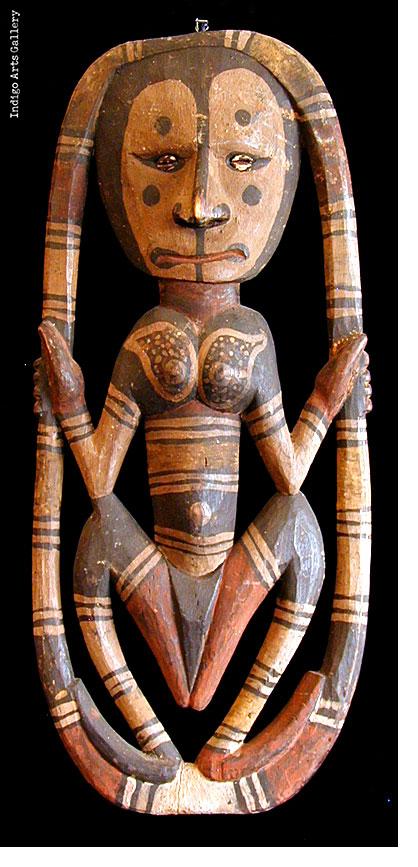

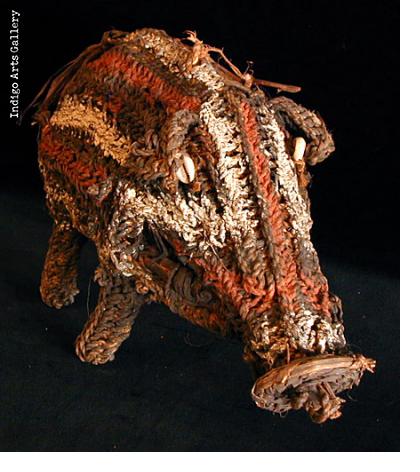

Orator's Stool (teket or kawa rigit). Iatmul people, Middle Sepik River, Papua New Guinea, mid-20th cent.

Caeved from single piece of wood, with organic pigments, shell eyes and pendants, fibre attachments.

(36 1/2" h. x 20" w. x 20" d.)

ex - collection of George Zafero, collected c.1970s.

Note: Due to size and weight, this piece will require custom art handling/packing/shipping, or direct pick-up by buyer. Please inquire for an estimate.

The latmul language group occupies the main part of the middle Sepik River. It is mainly through its prolific and varied art that the whole of the art of the Sepik River has become better known.

Generally, each main ceremonial house has a 'teket', which is used in much the same way as a lectern during formal discussions. The man speaking stands beside or behind the stool and emphasizes his points by beating the stool with three bunches of leaves which are provided. The head is set up on the shoulders, the face is rounder, the transition between brow and eyes is not clear-cut, the eyes are circular, the mouth is large, showing teeth (also found on some Yuat River figures). The nose, with its wide nostrils is emphasized by the vertical line rather than the carving. The roundness of the face at top and bottom is carried though the whole conception of the figure including such details as the pectoral muscles. The holes at the side of the head are for ties of string fibre to hold a small band of cane to which decorations were attached. There are the remains of red paint on the legs. The face itself is painted white, with red at the cheeks and mouth with the darker linear decoration being the wood itself. In Iatmul society it was the privilege of homicides only to paint their faces white and black. The 'teket' "are sacred and must not be casually touched and are not used as seats" (Gregory Bateson, 'Social structure of the Iatmul people of the Sepik River', Oceania, 2: 289, 260, plate 1, 1932).

Above text from AJ Tuckson, 'Some Sepik River art from the collection', Art Gallery New South Wales Quarterly, vol 13, no 3, 1972, pg. 671

This object was made by a member of the Iatmul [YAHT-mool] cultural group from the Middle Sepik region of Papua New Guinea (part of Melanesia). The religious life of the Sepik River was dominated by men’s societies, and wood carving of this kind was done exclusively by men. The artist who created this Orator’s Stool began by cutting the shape out of a large piece of wood. He then used sharp objects like obsidian knives or rodents’ teeth to further shape the figure and to carve details. To decorate the figure, he attached raffia around its waist, wrists, and ankles. He used feathers and shells to ornament the head. It’s possible that the artist painted the figure with charcoal, lime, or ochre.

This sculpture would have been kept inside a special house called a Men’s House, where Iatmul ceremonial activities often take place. Typically, each Iatmul community or town contains a few of these buildings, which serve as the center of community and celebration. The buildings are both visually imposing, as well as socially and spiritually influential. Women and uninitiated men are not able to enter the house.

WHAT INSPIRED IT

Every Iatmul community has its own ceremonial chair, similar to this one. This Orator’s Stool (also called a “speaking chair”) is not meant to be sat upon, but is used during village meetings, debates, and tribal ceremonies. During a discussion, the speaker stands next to the orator’s stool and hits the top of the stool with a cluster of leaves, sticks, and grass to validate important points in his argument. He also places leaves on the chair to confirm his statements. When the first speaker is finished and all the leaves lay on the chair, the next speaker can begin his address. After all of the speakers have stated their arguments, the village chief hits the chair a few more times and states a decision for all to follow. Orators also use these chairs to tell the comunity about the clan’s history and mythology while hitting the chair with a bundle of leaves to emphasize points.

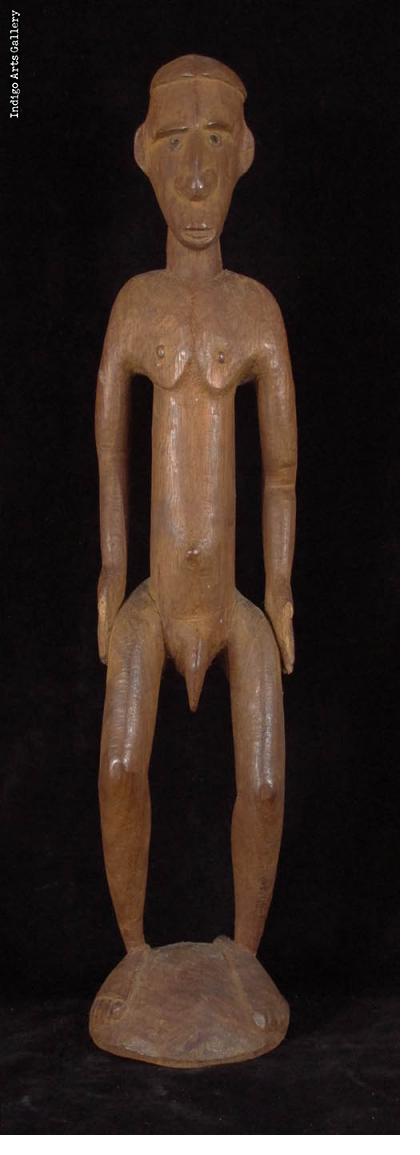

The human figure is a common form in Sepik River art. As seen in this sculpture, figures were often given an elongated head and torso and short limbs. Special emphasis was placed on the head to show that it is the most important part of the body, where the spirit resides. The artist carved an elongated nose, possibly in imitation of a bird’s beak, and the nose is pierced with ornaments made of bone or boar’s tusk, just as the Iatmul people wear. The incised patterns on the chest and arms represent scarification patterns that would be seen on many Iatmul men. Scarification is part of a young man’s initiation into the men’s secret society and the scars are considered marks of beauty and status.

Above text from description of similar piece at Denver Museum of Art.