Montu and Joba Chitrakar: Life is no scroll in the park

by AFisherMINHAZZ MAJUMDAR (Craft Revival Trust, 2004)

Montu and Joba Chitrakar, young, twenty-something couple, are at a crossroad. What should they do with the rest of their lives? What should they teach their children? Should they continue with things as they have been for hundreds of years or should they make a bold decision to break with the past? It’s not an easy dilemma to resolve for anyone, more so for them because they are no ordinary couple. Yes, they are poor and lead a difficult life, like millions of rural poor in India. However, they are also special because they are Chitrakars (traditional scroll painters and story-tellers) from West Bengal with a rich legacy, carriers of cultural customs centuries old in a rapidly changing modern world

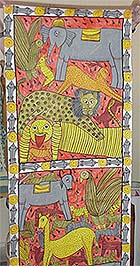

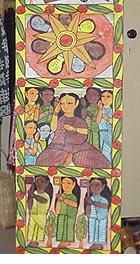

The Bengali scroll tradition is an ancient one, featuring long vertical multi paneled scrolls known as patas (paintings) or jorana patas (rolled paintings) since the scrolls are rolled up for storage and transportation. Each panel represents a particular sequence in the story and as they are unrolled for viewing, the accompanying couplet or story is recited. Painted on sheets of paper glued at the edges to form one continuous roll, these scrolls are mounted on cloth (usually old saris) for greater strength and flexibility. In most instances, the men are the painter-performers while the women make pinched clay figurines and toys. It is not essential for all the painters to be singers, with many preferring to paint and not perform. Traditionally, the performer would carry these scrolls from door to door, and depending on people’s request, particular stories would be narrated for a small fee, either in cash or kind. These scrolls were seldom sold, retained for performances and repaired occasionally till they became old and faded. Single image small paintings called chaukas were and continue to be made for sale during festivals and fairs.

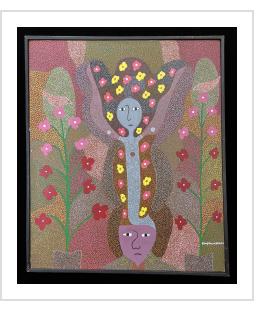

Bold swathes of colour punctuated by thick black outlines are a defining characteristic of this style of folk art. The forms are fleshed out, the lines gently undulating – the overall impact is dramatic and sensuous, with no hint of sharp angularity or rigid geometric forms. While the style of painting is consistent, the themes of the scrolls vary greatly - they can be religious or secular subjects such as the great Hindu epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, local folklore and topical social and political issues. Bengali religious practices such as the worship of the Great Goddess Durga or the Snake Goddess Manasa are highlighted in many scrolls. Episodes from the lives of popular Gods such as Krishna and Rama are also very common. Secular scrolls often deal with stories of India’s freedom struggle and major turning points in modern Indian history such as the assassinations of former Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi and her son Rajiv Gandhi. The narrative aspect of this scroll painting tradition lends itself very well to the depiction of social issues such as the need for family planning, AIDS prevention, environmental awareness, immunization, anti-dowry campaigns, etc. In fact, this art form holds great potential to be an effective tool in awareness generation.

Montu Chitrakar, born into a scroll painter’s family, has been playing with colours since he was a child, much like his own son Sanjay, who at nine turns out charming pictures. Montu began early, learning from the elders in the extended family, imbibing both consciously and unconsciously all the identity markers of his tradition. He learnt how to paint and colour, painstakingly preparing all his paints from natural elements – the black of burnt rice husk, the yellow from turmeric, mixing each colour with the sticky fluid of the bael (wood apple). He learnt how to sing the traditional Bengali songs, learning not just the words but to use his voice as a powerful instrument. He memorized stories from the holy books, folk tales and local myths, committing them to his heart. Soon, he was the painting, the song, the story – he became one with his art.

Montu’s passion for the art form he practices sets him apart, both as an artist and a person. There is no mistaking the pride he takes in his work, the soaring energy of his voice as he sings out the story in the scroll. So powerful is his involvement in his art that watching him perform is guaranteed to stun you – you may not understand the language he sings in (Bengali) but you surely can recognize the pathos, the pain, the anguish and the joy. Watching him unroll the scroll frame by frame and pour his heart out in his singing out the story, you are elated - this is truly communication without language, akin to a deeply satisfying spiritual experience, the sheer brazen power of his voice, singing with no accompanying instruments taking you on an intense journey. For a moment, you feel awkward, his deep involvement in the moment and his total lack of self-consciousness in a way drawing out your own “non-committal” stance in life. Either way, here is a performance that will not leave you untouched – for Montu, his art is not just his livelihood but also his life.

His desire to innovate with form and content has taken him far in his artistic odyssey. He is hungry all the time for fresh ideas and stories, anything to push the boundaries of his art. News on the radio, films he has watched in languages he does not understand, stories he has heard, conversations swirling around him – everything is grist to his mill. His works of art are created like a pearl in an oyster – a central idea onto which layers of meaning and imagery are added slowly to build up to an impressive finale. His repertoire of scrolls includes traditional religious and folk tales as well as topical issues such as the earthquake in Gujarat, religious riots, women’s rights, AIDS and the environment. Within the spatial confines of the scroll format, he explores new worlds and vistas, some of them million times removed from his own. He experiments with cultural barriers, telling a familiar story in an unfamiliar manner – his scroll on the French revolution depict very Indian faces and is accompanied by a song in Bengali but is painstaking in attention to historic authenticity, featuring in the last panel, a guillotine with a severed head.

Combining song and drawing to effectively tell a story requires the artist to be a master of several skills. One needs to have a highly developed sense of form and content and the ability to relate a static medium (the painted paper) with two dynamic processes (singing and story-telling). One needs to be able to compose, to emote and to convey meaning to the painted world depicted in the scroll. Montu is able to do this with great panache - the scroll on the devastating earthquake in Gujarat in 2001 begins with an uprooted tree painted hanging upside down, the roots sticking out in the air. This stark, dramatic image sets the tone for the song that is in essence, a lament for those dead and those left bereaved. One of his most powerful scrolls was the result of listening to news reports on the violent Hindu-Muslim riots in Gujarat. “The Gujarat Riot” scroll is compelling , not just in its visuals but also for the song he specially composed which has a very moving refrain “Ek Maaer Santaan “ which translates into “We are the Children of One Mother”.

Joba Chitrakar began painting after her marriage and the birth of her children. At first she was hesitant, afraid that she would spoil the paper and waste the paint. She began by filling in the blocks of colour in Montu’s larger paintings so that he could concentrate on working on the details and outlines in black. Soon, she wanted more – not content with colouring Montu’s work and not wanting to blindly copy his work, she began experimenting on small sheets of paper. She had seen many old Santhal jadupatua scrolls from eastern India, depicting the Santhal story of origin and village customs. Inspired by these, she began creating small drawings and then moved onto larger scrolls depicting Santhal village life – scenes of hunting, dancing, working in the rice fields. Her work differs from the original in that she uses colourful backgrounds and thick, bold strokes whereas in the jadupatua scrolls, the drawings are thin and delicate against a white base. She has created her own reservoir of imagery, her own style of painting in a very short while, graduating from being an understudy to a full-fledged artist. Though nowhere as prolific as her husband, she is creating a niche for herself as an individual artist, learning some of the songs and overcoming her shyness to sing in public.

Clearly, a fascinating world of art and culture, poetry and performance permeates the lives of this young couple. But life is uncertain – what social and financial guarantees does the future hold for them? Time has played a nasty trick on them – on one hand, museums, universities and private collectors abroad are keen to buy examples of their work and on the other, the spread of cable television and rapid urbanization has swallowed a large segment of their traditional audience. The collectors and institutes value the art as a “dying and disappearing art form” and have a limit on how much they can or are willing to buy. What happens when they reach their saturation point – when buying more does not make sense? Where is the new audience for Montu, Joba and others like them? Their scrolls, out of context, are “too long to hang up on the wall”, too bulky to store”. Who has the time to sit through a performance that too in a language one does not understand, at a time when email, SMS and mobile telephones wrap you in one continuous thread of connectivity? Where do Montu and Joba go from here? Life is no scroll in the park