The following information was prepared for the award-winning exhibition, Dancing Shadows, Epic Tales: Wayang Kulit of Indonesia, which was developed by the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico and was on display from March 8, 2009 through March 14, 2010.

Wayang kulit performance of Indonesia is among the greatest story-telling traditions in the world and lies close to the heart of Javanese culture.

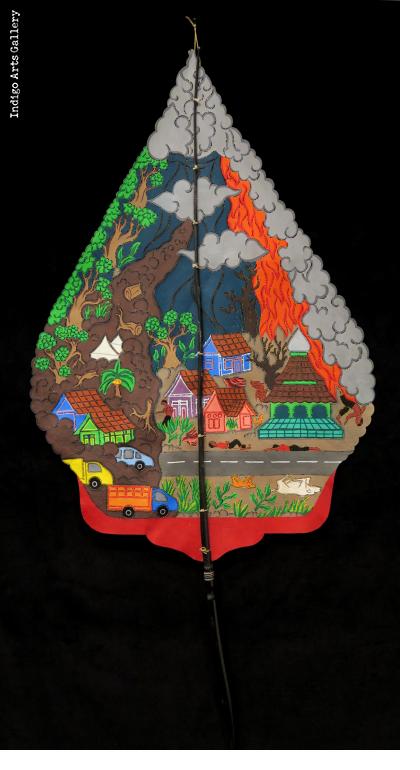

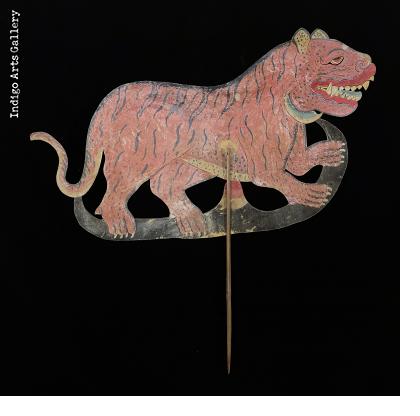

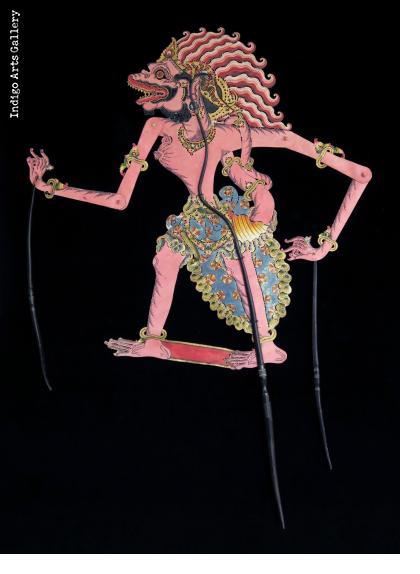

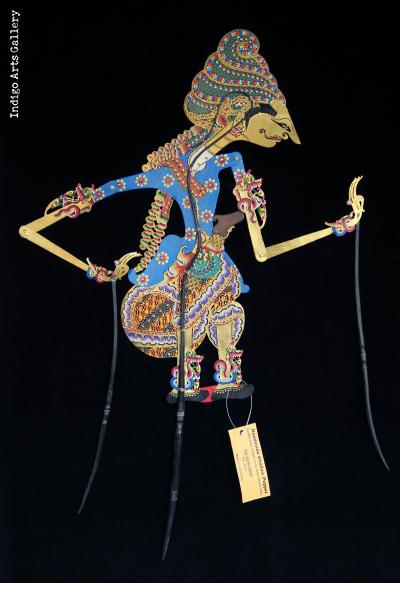

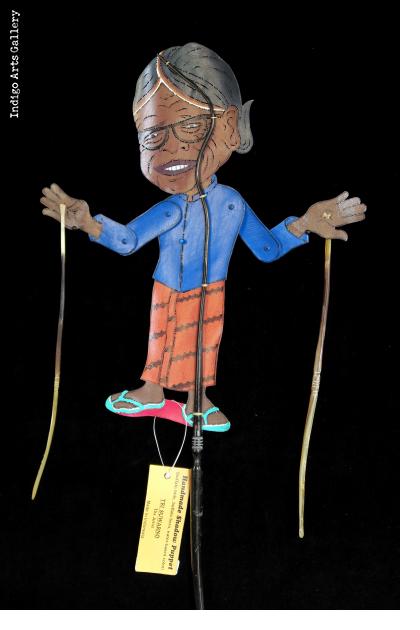

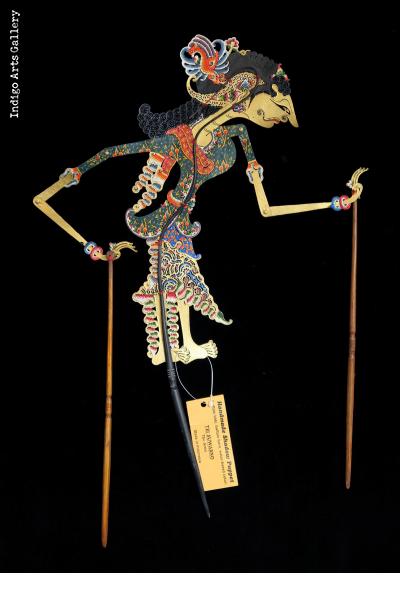

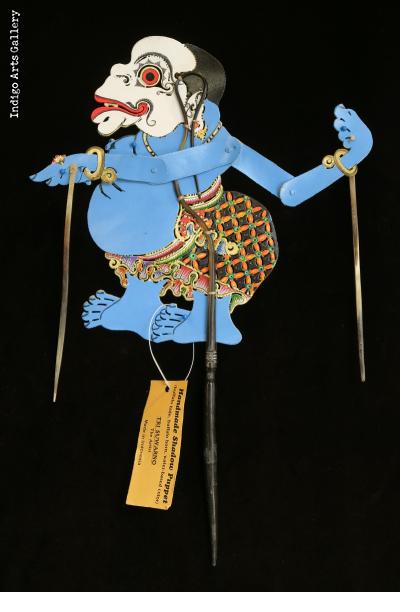

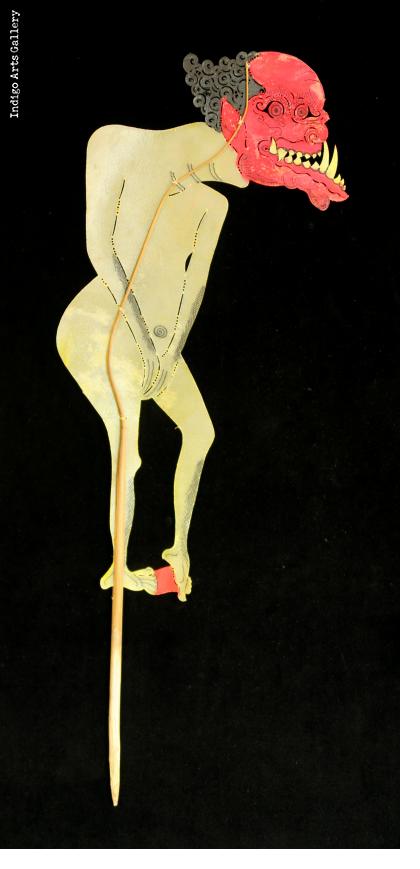

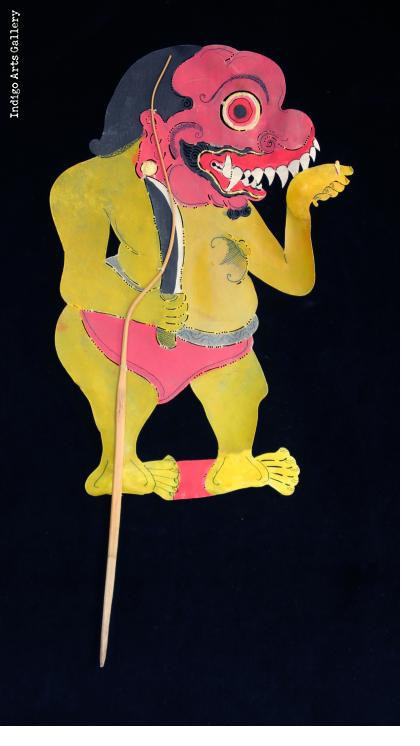

Wayang kulit are shadow puppets. Yet, more than mere puppetry, this is one of the highest forms of art in Indonesia. Traditional performances are based on classical literature. Each show teaches important morals and involves serious philosophical contemplation, while entertaining the audience at times with roaring humor and special action-packed scenes. Traditionally, performances last all night, beginning in the evening and ending at dawn and are always accompanied by a gamelan orchestra, creating a dynamic, multi-sensory experience.

The tradition of wayang kulit has been performed in villages, cities, and royal courts for hundreds of years and is very much alive today. This exhibit focuses on the style of wayang kulit from Surakarta, a Central Javanese city commonly referred to as Solo.

Wayang Purwa: Repertoire and The Cast Of Characters

The term wayang purwa refers to four cycles of epics, which began to be standardized by the royal courts of Central Java in the eighteenth century. The two most popular and commonly performed of these epics are the Mahabharata and Ramayana.

Wayang stories involve moral and ethical dilemmas faced by the characters in their journeys through life, love, and war. The stories are about good versus evil, but more than that, they contemplate the existential struggle between right and wrong. They are about the pursuit of living a virtuous, noble life and the search for meaning. The means to those ends are not always clear cut. “Good” characters may posses certain negative traits and likewise, not all the “bad” characters are entirely immoral. Whatever the circumstance, wayang stories always present philosophical ideas and poignant messages.

Historic Roots

The Hindu stories, Mahabharata and Ramayana, originated in India possibly as far back as the eighth century BCE and reached Java around the eighth century CE. For centuries, Hinduism was the predominant religion of Java. Over time, the epics became distinctly Javanese versions of the original Indian texts and by the tenth century they were recited in the form of wayang kulit as court-based theater. Most likely, the Hindu stories were applied to indigenous beliefs and local shadow puppet traditions, melding into a uniquely Javanese custom.

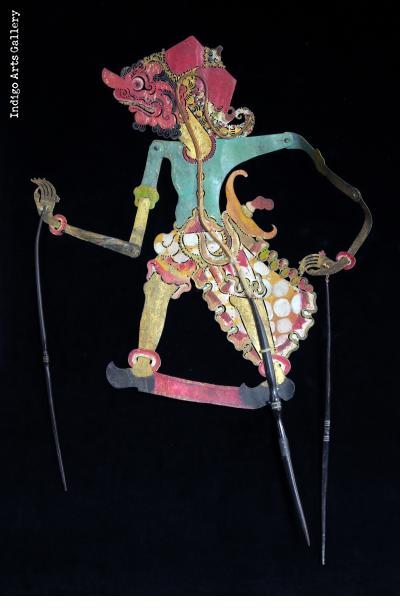

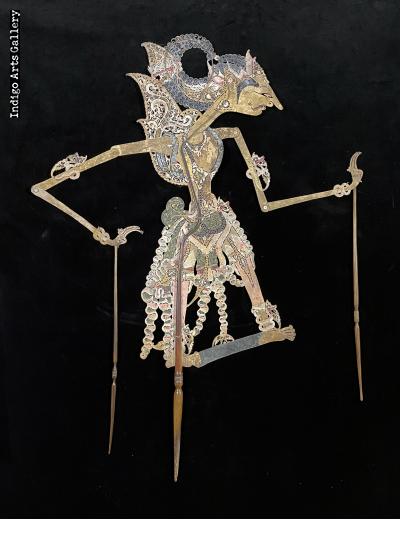

When Islam took hold in Java (1200 – 1600), the current stylized form of wayang kulit was adopted to meet cultural prohibitions on representation of the human form. The aesthetic traits of the puppets persist and Islam’s presence on Java remains strong, while the Hindu body of literature continues to be an important part of Javanese art and culture to this day.

The Epics

The epics are divided into over 200 distinct and autonomous, yet related episodes (lakon), which are the stories presented in singular, nine hour performances of classical wayang kulit in Central Java.

How Wayang Kulit Are Made

The art of creating wayang kulit is incredibly detailed. Several artists are usually involved in the different stages required to make a single puppet. These artists often learn the art from family members and apprentice with a master, and in the past they may have also studied at the kraton (palace).

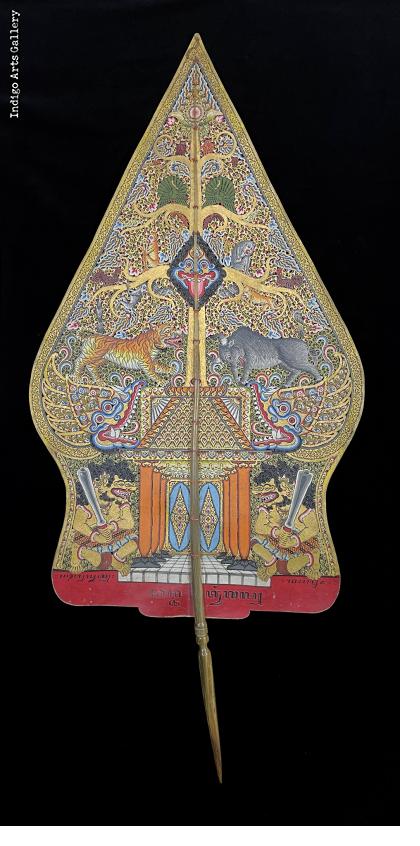

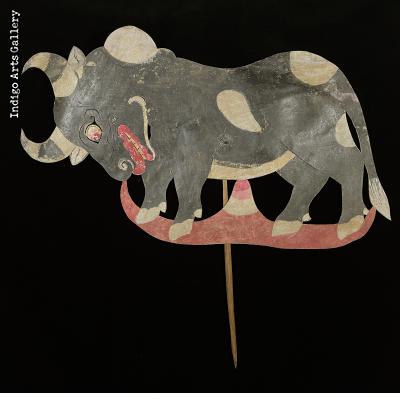

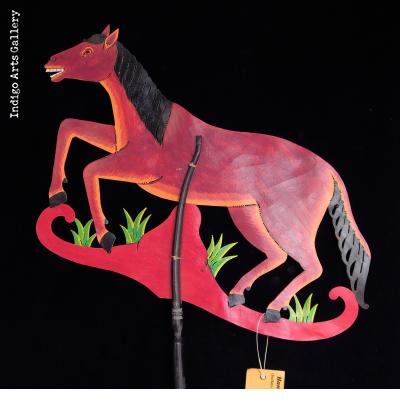

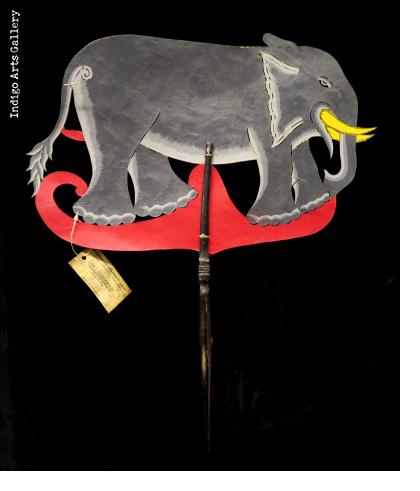

Wayang kulit are made from water buffalo hide, cut and punctured by hand, one hole at a time. The artists who carve and puncture the water buffalo hide begin by scratching the outline and details of the wayang figure onto the rawhide. The carving and punching of the rawhide, which is most responsible for the characters’ portrayal and the shadows that are cast, are guided by this sketch. A mallet is used to tap special tools, called tatah, to punch the holes through the rawhide. The tool only comes in two basic shapes, flat and curved, but they do come in a variety of sizes. Most punches require several turns of the tatah to achieve the desired detail. This is the most time-consuming stage of the puppet-making process.

Once the hole-punching is complete, the puppets are painted in layers of water-based paints, heavily decorated with extraordinarily fine details, and often finished with gold or bronze leaf.

The sticks attached to the base and articulated limbs of the wayang kulit are made from water buffalo horn and / or wood. Making the puppet sticks from horn involves a complicated process of sawing, heating, hand-molding, and sanding until the desired effect is achieved. When the rest of the puppet is ready, the artist attaches the handle by carefully and precisely molding the ends of the horn around the individual wayang figure and it is secured with a needle and thread.

A large character may take five months or more to produce.

Text courtesy of Museum of International Folk Art - Santa Fe, New Mexico