About the Artist

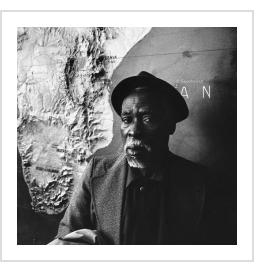

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, also known as Cheik Nadro (Zépréguhé, Ivory Coast, March 11, 1923 - January 28, 2014) following per Wikipedia:

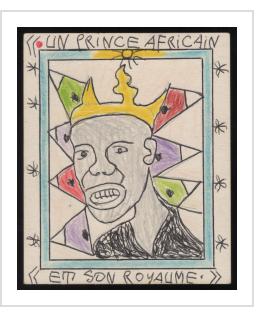

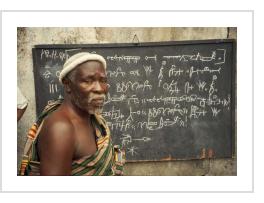

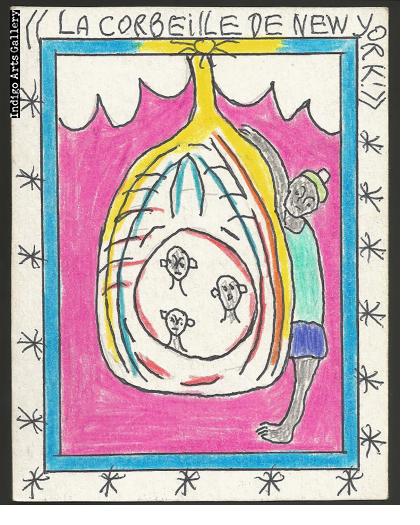

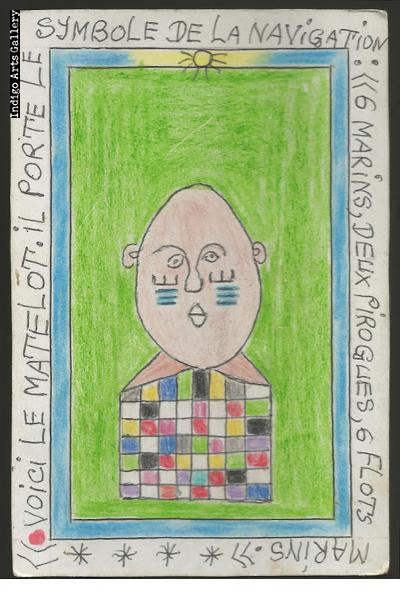

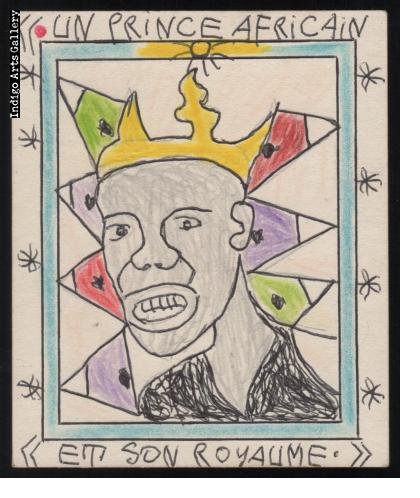

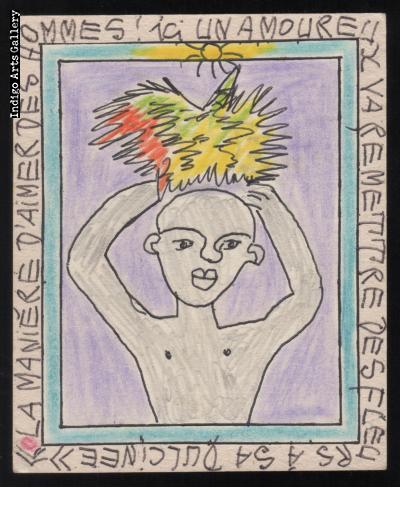

Bouabré was born in Zépréguhé, and was among the first Ivorians to be educated by the French colonial government. On March 11, 1948, he received a vision, which directly influenced much of his later work. Bouabré created many of his hundreds of small drawings while working as a clerk in various government offices. These drawings depict many different subjects, mostly drawn from local folklore; some also describe his own visions. All the drawings are part of a larger cycle, titled World Knowledge. Bouabré also created a 448-letter, universal Bété syllabary, which he used to transcribe the oral tradition of his people, the Bétés. His visual language is portrayed on some 1,000 small cards using ballpoint pens and crayons, with symbolic imagery surrounded by text, each carrying a unique divinatory message and comments on life and history.[2]

Many of Bouabré's drawings are in The Contemporary African Art Collection (CAAC) of Meshac Gaba. One of his emblematic drawings is saved in the L'appartement 22 collection on the African continent: "Une divine peinture relevée sur le corps d'une mandarine jaunie", made by Bouabré in 1994 in Abidjan.

Exhibitions

- 2013 Venice Biennale, Italy.

- 2012 Inventing the world: the artist as citizen, Biennale Bénin, Cotonou, Bénin.

- 2010-2011 Tate Modern, London, UK

- 2010 African Stories, Marrakech Art Fair, Marrakech

- 2007 Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK

- 2007 Why Africa ?, Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli, Turin, Italy

- 2006 100% Africa, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain

- 2005 Arts of Africa, Grimaldi Forum, Monaco, France

- 2004-2007 "Africa Remix", the touring show has started on 24 July 2004 at the Museum Kunst Palast in Düsseldorf (Germany), and travelled to the Hayward Gallery in London, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo.

- 2003 Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Musée Champollion, Figeac, France

- 2002 Documenta 11, Kassel, Germany

- 2001-2002 "The Short Century", was an exhibition held in Munich, Berlin, Chicago and New York and organised by a team headed by Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor

- 1996 “Neue Kunst aus Africa”, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germania

- 1995 Galerie des Cinq Continents, Musée des arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie, Paris, France

- 1995 "Dialogues de Paix ”, Palais des Nations, Geneve, Switzerland

- 1994 “Rencontres Africaines”, the touring exhibition has shown in Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, Cidade do Cabo in Sud Africa, Museum Africa in Johannesburg and in Lisbon(Portugal).

- 1994 “World Envisionned”, together with Alighiero Boetti, the exhibition has shown in DIA Center for the Arts in New York and American Center in Paris.

- 1993 “Trésor de Voyage”, Biennale di Venezia in Venice (Italy)

- 1993 “Azur”, Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain in Jouy-en-Josas (France)

- 1993 “La Grande Vérité: les Astres Africains”, Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes (France)

- 1993 “Grafolies”, Biennale d’Abidjan in Abidjan (Ivory Coast)

- 1992 “A Visage Découvert”, Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain in Jouy-en-Josas (France)

- 1992 “Oh Cet Echo!”, Centre Culturel Suisse in Paris

- 1992 “Out of Africa”, Saatchi Collection in London

- 1992 “L’Art dans la Cuisine”, St. Gallen in Sweden

- 1992 “Resistances”, Watari-Um for Contemporary Art, in Tokyo

- 1991 “Africa Hoy/Africa Now”, the touring exhibition has shown in Centro de Arte Moderno in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain), Gröninger Museum in Groningen (Netherlands), Centro de arte Contemporaneo in Mexico City

- 1989 “Magiciens de la Terre”, Centre Georges Pompidou and Grande halle de la Villette in Paris

- 1989 “Waaah! Far African Art”, Courtrai in Belgium

- 1986 “L’Afrique e la Lettre”, Centre Culturel Français, Lagos in Nigeria

From March 13 to August 13, the Museum of Modern Art mounted the exhibition:

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound

The work of the Ivorian artist Frédéric Bruly Bouabré had a single objective: to record and transmit information about the known universe. Devoting his life to a quest for knowledge, Bouabré captured and codified subjects from a range of sources, including cultural traditions, folklore, religious and spiritual belief systems, philosophy, and popular culture. “I do not work from my imagination," he once said. “I observe, and what I see delights me.”

The first survey of Bouabré’s work, and the first exhibition at MoMA devoted to an Ivorian artist, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound spans the artist’s immense production from the 1970s until his death in 2014. A highlight of the exhibition is the Alphabet Bété—Bouabré’s invention of the first writing system for the Bété people, an ethnic group in present-day Côte d’Ivoire to which the artist belonged. Also on view are hundreds of postcard-size illustrations that he drew on cardboard packages of hair products he salvaged from his neighborhood in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire’s economic capital. Tracing the arc of Bouabré’s inventiveness—from the creation of his first writings and drawings focused on the the culture of the Bété, to scenes from everyday life exploring broader themes of democracy, women’s rights, and current affairs—the exhibition celebrates his commitment to collecting, preserving, and sharing knowledge as a way of understanding the world around us.

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: Self-Taught Encyclopaedist

by Sarah Lombardi in Raw Vision #69

In Dakar, on March 11th of the year 1948, the Ivorian creator Frédéric Bruly Bouabré (b. ca. 1923) had a revelation exhorting him to spread his knowledge of the world and of his people (the Bété) as widely as possible. To that end, he invented a ‘Bété alphabet’. (1) As often occurs among creators of Art Brut, it was an outside element that incited him to create this new writing system. Not, however, in the sense of hearing a voice, like Augustin Lesage, or of having one’s hand guided by an external spirit, like Rosa Zharkikh or Raphaël Lonné, but in that of a solar vision: on his way to work one day, he suddenly saw seven differently coloured suns orbiting in the sky. So did the Heavenly Father reveal Himself to him, endowing him with the power to interpret his worldly surroundings. Adopting the name Cheik Nadro-le-Révélateur (the Revealer), he went on to devote himself to teaching the divine truths imparted to him in his dreams. (2)

Charged with this new mission, Bouabré applied himself to transcribing forms he discovered on small stones found in the Bété village of Békora that were renowned for their motifs and mysterious origins. After collecting and studying the stones as might an encyclopaedist, he concluded that they depicted the remnants of an ancient writing system. He went on to match the forms he discovered with phonemes from the Bété language, linking these to syllables from the French language and thus creating an alphabet consisting of 448 monosyllabic pictograms. The resulting syllabary can be used in all languages, much in the utopian spirit of inventing Esperanto as a universal second language.

In short, Bouabré translated the Bété language, which until then had only been handed down orally, into its written equivalent. His goal was to safeguard his culture by putting it into writing, thus ensuring it would last and be remembered. As such, he also furnished the African language with a writing system of its own and, by the same token, took his revenge on the colonialists who imposed their European alphabet on Africa. Furthermore, he set about spreading his ‘African writing’ by recording it in school notebooks to facilitate its teaching and usage. Begun in 1956, and completed during the first three months of 1958, his alphabet was published that same year by Theodore Monod, director at the time of the French Institute of Black Africa (IFAN) in Dakar. Intent on proving the usefulness and universal quality of his invention, Bouabré himself put it into practice by translating all sorts of texts into his invented written language: poems, stories, encylopedic pages and even political speeches. Subsequently, he took to researching body markings (scarifications), this time recording the bodily cuts and scratches he came across to translate them into graphic form. Grouped together, they became his Musée du visage africain (Museum of African Faces), launched in 1965...

Ivory Coast artist Frederic Bruly Bouabre dies

(BBC News 29 January 2014)

One of Africa's most celebrated visual artists, Ivorian Frederic Bruly Bouabre, has died aged 91.

Bouabre created many of his hundreds of small drawings while working as a clerk in various government offices.

He also created an alphabet of pictograms to transcribe the oral traditions of his people, the Betes.

In the last 25 years his work has been exhibited at several of the world's most important art galleries and museums.

He thinks it's easier for an African to learn, to get new knowledge, when he works inside an African writing system

Yacouba Konate, Ivorian art critic

His work was displayed at last year's Venice Biennale, both at the international exhibition, called The Encyclopaedic Palace, and at the Ivory Coast pavilion.

"Bouabre is himself a kind of builder of encyclopaedias because his personal work consists in inventing a specific African alphabet," the Ivorian curator and art critic Yacouba Konate told the BBC at the time.

"He thinks it's easier for an African to learn, to get new knowledge, when he works inside an African writing system, an African language."

Mr Konate said Bouabre also documented the scarification on people's faces in various West African countries.

According to the Venice Biennale organisers, Bouabre worked as a civil servant until 1948, when he had a vision after which he dedicated himself to art.

Jonathan Watkins, from the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham and curator of a recent an exhibition of Bouabre's in Seoul, said during the vision he saw different coloured circles in the sky.

"It lead him to the conclusion that he was put on earth as a kind of prophetic character. He called himself 'Cheikh Nadro'.... 'the one who never forgets,'" he told the BBC's Focus on Africa radio programme.

His visual alphabet language was portrayed on more than 400 small cards using ballpoint pens and crayons, with symbolic imagery surrounded by text.