About the Artist

Clotaire Bazile (1946 - 2012*)

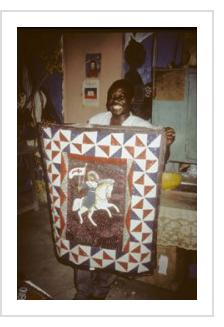

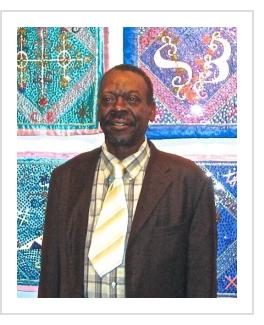

Clotaire Bazile was a Vodou priest, a healer, and one of Haiti's most famous flag makers. Bazile became a priest of Vodou in 1971, at age 25, and he made his first ritual flags two years later. He received not only his initial mandate to make flags, but also all of his artistic training, from spirits that came to him in dreams. The first flags he made were sacred ceremonial ones for use in his temple, but soon afterward he began creating non-sacred versions for sale to tourists who were beginning to demonstrate an interest in the art form. He formally opened a flag-making workshop in Port-au-Prince in 1980, and it is still in operation, providing work for members of his religious community and bringing much-needed funds into the temple.

Other Vodou priests followed his lead and established their own workshops, and over the subsequent decades, numerous artists of other religious faiths have emerged with their own distinct personal styles of flag making. The result has been a cottage industry in sequined works of art that have made their way into galleries and boutiques throughout the United States and Europe. Bazile was one of the key actors in this transition of Vodou flags from primarily ritual objects to commercial art objects. Bazile describes his work as a priest and his work as a flag maker as intertwined and mutually enabling. "Flags are unlike other kinds of art objects," he observes, "because the spirits are involved. The spirits are in the symbols of the flags. Not with all their power, because you can't reveal all their secrets, their force. If you don't reveal the power, if you don't baptize the flag, it is just an object. Neither the people who buy them nor myself have any problems. It's with the spirits' permission that I make the flags."

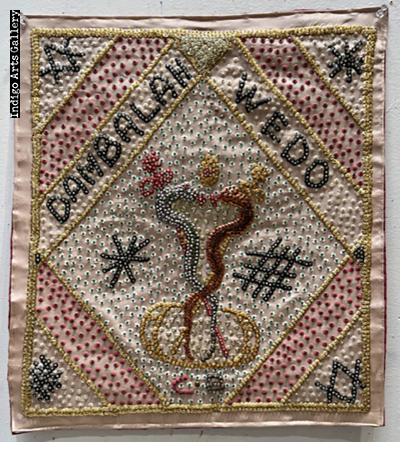

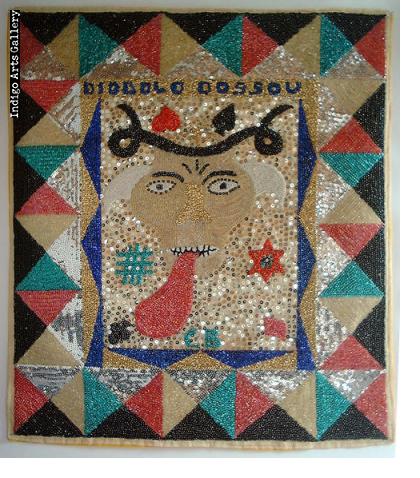

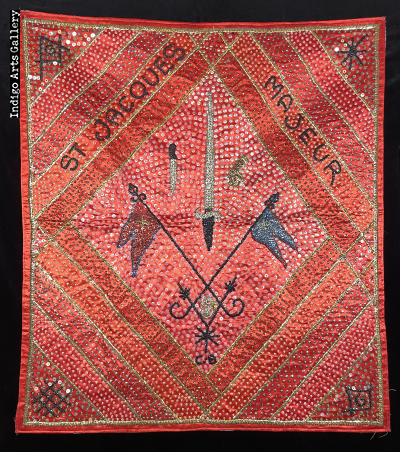

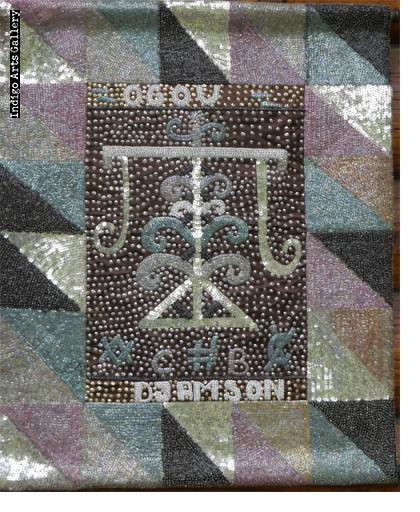

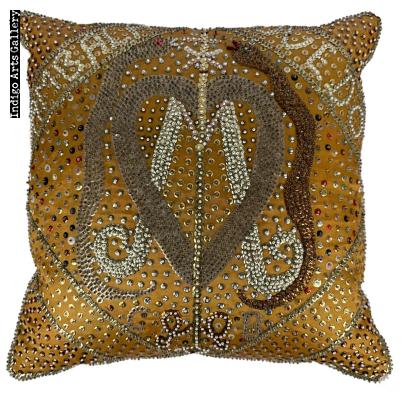

Haitian Vodou is a syncretic religion that originated during the early days of French colonialism in Haiti; it combines African tribal beliefs, Muslim influences, and 16th- and 17th-century European Catholicism. The sacred ritual flags reflect these same geographical and cultural influences, including the textile traditions of Africa and 18th-century French military flags. The flags are glittering, multicolored squares of silk, cotton, or velvet, usually about three feet square and adorned with appliqué and sequins. The designs may take the form of complex geometric diagrams or representational imagery, but each flag always depicts a Vodou spirit (of which there are dozens) and indicates his or her personality, sacred days, and associated tree or color.

Bazile's flags have been characterized as having a special clarity and boldness in their depiction of Vodou icons and emblems. According to Virgil Young, an early collector, Bazile was the first of the flag makers to achieve a "consistent level of perfection" in his work. The artist himself describes his flags as classical in style, with an aesthetic that deliberately looks back to flags made in the mid-20th century. Each Vodou temple owns at least one pair of ritual flags, among many other sacred objects. As an integral part of every Vodou ceremony, two flags are tied to poles that are held aloft and touched together. Special guests walk under the crossed flags, which offer respect to and welcome the spirits before they possess the worshippers. Prayers are offered, drums are beaten, sacred songs are sung, and participants dance as the spirits enter their bodies. The flags thus help bridge, both literally and metaphysically, the human and spiritual worlds.

Above notes by Lindsey Westbrook on the California College of the Arts website, posted March 16, 2010, courtesy of the California College of the Arts. The text was based on information provided by Susan Tselos, and writings by Anna Wexler, including interviews with Clotaire Bazile and the late collector Virgil Young (see "I Am Going to See Where My Oungan Is": The Artistry of a Haitian Vodou Flagmaker, by Anna Wexler, published in the collection Sacred Possessions (Rutgers University Press, 1997).

*Clotaire Bazile disappeared on a visit to Haiti in October, 2012, and as of this writing is presumed to be deceased.