About the Artist

Ishola Folorunso (1949-2021)

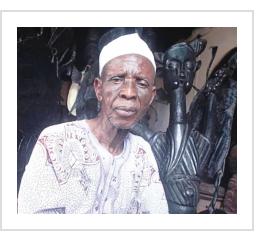

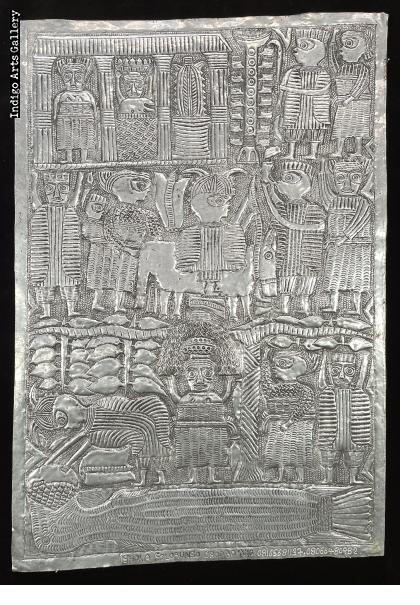

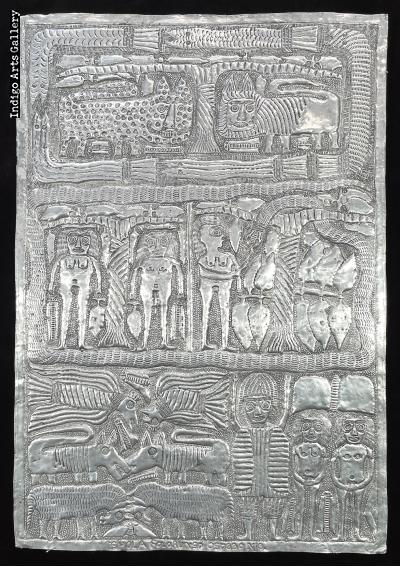

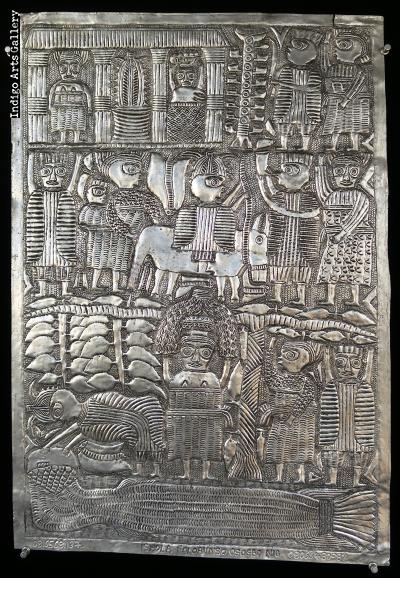

A member of the second generation of aluminum relief artists in Oshogbo, Nigeria, Ishola Folorunso (also spelled Isola Folorunso) was born c.1949. A son of Yekini Folorunso and a nephew of the great Asiru Olatunde, he was associated with the Oshogbo Art Movement and New Sacred Art, founded by Adunni Olorisha (Susanne Wenger). He passed away on May 31, 2021. His son, artist Toyin Folorunso, passed away in 2023.

Isola Folorunso: From blacksmith to global artist

Nigerian Tribune, January 24, 2021

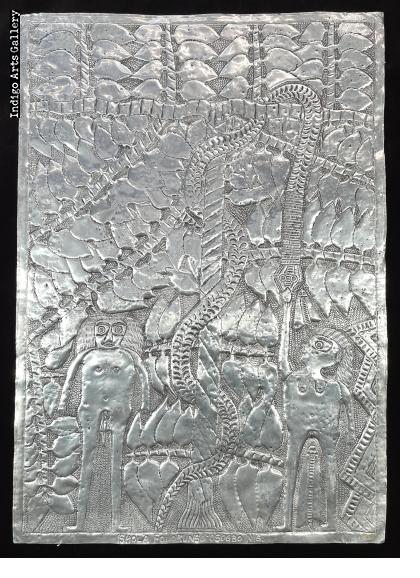

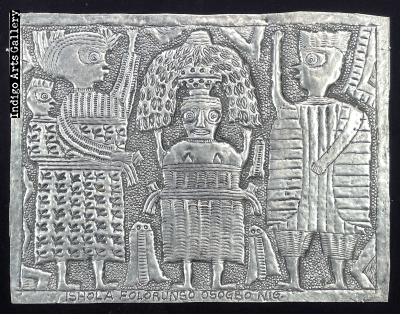

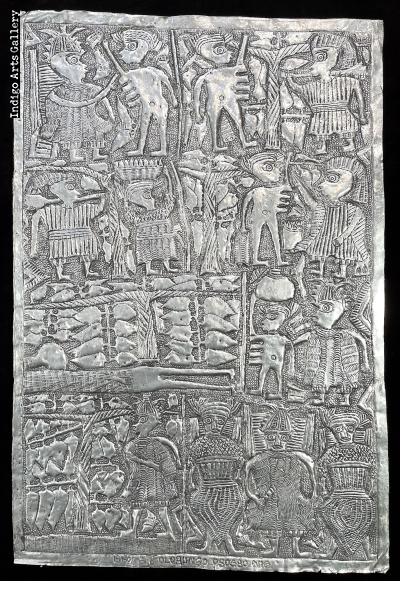

Septuagenarian artist, Isola Folorunso is renowned for beaten metal form. He makes impressive artworks from aluminium, copper and brass. The widely exhibited but reticent artist who executed the friezes at the National Theatre for the late Erhabor Emokpae, shares his journey into art in a recent encounter.

PA Isola Folorunso’s fame is bigger than his frame. Art collectors worldwide, particularly those whose preference is beaten metal works – aluminium, brass and copper – are familiar with him. His highly sought-after works have reached places that he has not been to, and would most likely never go. Slight in build, hugely skilled and soft-spoken, he is an artist whose fame rightly precedes him. After all, how many artists had the opportunity of training under the great Asiru Olatunde, inventor of the art form (beaten metal)?

Artists from Osogbo belong to two leading schools; the Osogbo Art Movement emerged from workshops the late Ulli Beier and his wife, Georgina, held in the 1960s. The New Sacred Art was founded by artist and High Priestess of Osun, Susanne Wenger, also known as Adunni Olorisha.

Like Olatunde, his master who had a close relationship with Beier and Wenger, Folorunso also worked with the duo. He, however, identifies with the Sacred artists. His exquisite art has brought him fame, if not wealth. He’s wearing Ankara buba and sokoto with a cap the afternoon we meet at Wenger’s iconic house at Ibokun Road, Osogbo.

Like Elisha who inherited Prophet Elijah’s mantle, Folorunso got that of his boss, Olatunde. He recalls how it happened.”I was born into a blacksmith family, and when Ulli Beier was in Nigeria, he used to come to the forge. Our father, Asiru Olatunde, was our boss. Whenever Beier came occasionally, he would watch how we were making ear-rings, rings and bracelets. He watched how we made drawings on them. He was surprised that we were drawing lions, tigers and human heads and snakes very clearly.

“One day, he encouraged Baba Asiru to do several works that he needed them for something. He also asked Baba if he had any wider object that he could draw on apart from the rings and ear-rings. Baba said he didn’t. Beier then travelled to Ibadan and bought aluminium, copper and brass. He told Baba Asiru to start drawing all he was doing on ear-rings, ear-rings and bracelets on the materials he purchased.

“Baba started doing so, and after an extended period, Ulli Beier came, packed everything and travelled to Lagos. Upon his return, he went to give Baba money. That it was from sales of the artworks, he advised Baba to work harder than previously. So, Baba heeded his advice. When the materials he brought were exhausted, Beier would return to buy more from his pocket.

“When Baba finished working on the materials, Ulli would sell them and bring the money to Baba. He started becoming happy and motivated. Later, Ulli Beier married Georgina, who was an artist. She also encouraged Baba and showed him other innovations he could introduce to his art. From then onwards, the work started growing broader slowly. Beier could take the art pieces to the University of Ibadan, or the University of Lagos. Later, he found a way to introduce Baba’s works abroad. They would write to commission specific pieces or that a special exhibition was about to happen. We would then post them [artworks] at Ikeja. You could only go to Ikeja then. Until Baba’s death, he would take at least the second position whenever any world exhibition happened.

“After Baba’s passing, the question then became who would supervise the works? I was the closest to Baba; I understand the art very well. All Baba could do, I can also do. When we are drawing, we won’t hold any paper or sketch it previously. We use our imagination and draw whatever we want to create.

“If you commission us for a job, once you tell us what you want. If you like, you can give us a picture. If you do not wish, don’t give us but explain what you want. By God’s grace, we would create it exactly the way you want it. After a long time, I changed some things in the way we make the works—the way we made the cuts. We previously used to make the small cuts on the stone, and it wasn’t smooth, level.”

The late artist, Erhabor Emokpae is credited with creating the elaborate frieze at the National Theatre, Iganmu Lagos entrances. Though the conception was all Emokpae’s, the execution wasn’t. He sought out Folorunso and others from Osogbo who helped him create the friezes.

“When Emokpae heard about our name and work, he came here to Osogbo,” the artist begins. “He told us he had a job for us, that it was big. Could we come to Lagos? I told him I would, and he returned to Lagos. We spent six months creating the works at the National Theatre. He lodged us at a hostel and bought a huge iron sheet. That instead of placing our materials on stone, we should be using the iron; that the works would be smoother. We saw that it was true. Emokpae was very happy with the job, and he did very well by us. He was a very good man. His death pained us because he wasn’t arrogant.

“He had no airs despite his education and wealth; the way he related with his children was the same way he did to visitors. The work we did for him was the frieze at the entrance. If you go down, you would see some copper, but we used his drawings.”

But Lagos wasn’t the only place the Septuagenarian was commissioned to work. “Ayo Odiboh in Benin City also invited us for a job. He lived at 12, Sakpoba Road, Benin. We spent nearly one year there. It was also a copper job, and we completed the job. Since then, I have been my master. People who knew Baba from the US but who had started seeing my name started commissioning me too.”

Making beautiful artworks on aluminium and copper is not easy, and Folorunso shared how he achieves results. “We temper aluminium with fire. We put it close to fire to soften, but you must be very vigilant. If you are not, it will melt. If the aluminium is not soft enough, it would be puncturing when you start working on it. Copper doesn’t need softening. Once you buy it, you work according to the size you are to make.”

Fittingly, Pa Folorunso also learnt succession planning from his master. Unlike some craftsmen who wouldn’t teach others their art for reasons best known to them, Folorunso teaches others, including his children.

“One of my children; not the firstborn, has mastered the skill and is in the US. His name is Jelili Oloruntoyin. Later, a child that I can refer to as my last; Taofeek Adebayo, also joined. The duo is also in the line and has mastered it. As I’m getting old, commissions that I now get, they are the ones that execute it. I sit and supervise them.”

It couldn’t have been any other way. This famous Osogbo artist has earned his spurs. Wealth to live his old age in comfort is all that remains. And may it come.