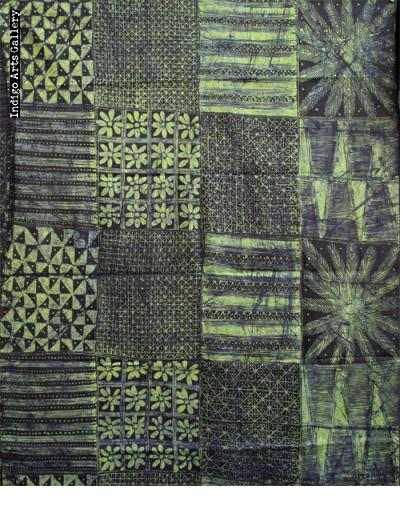

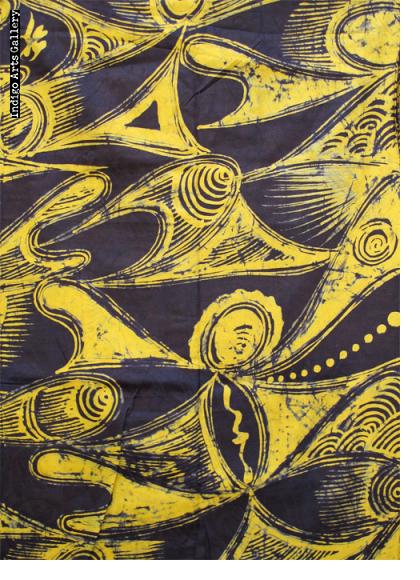

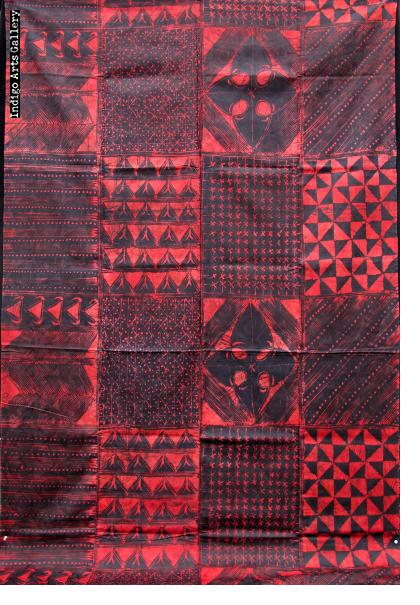

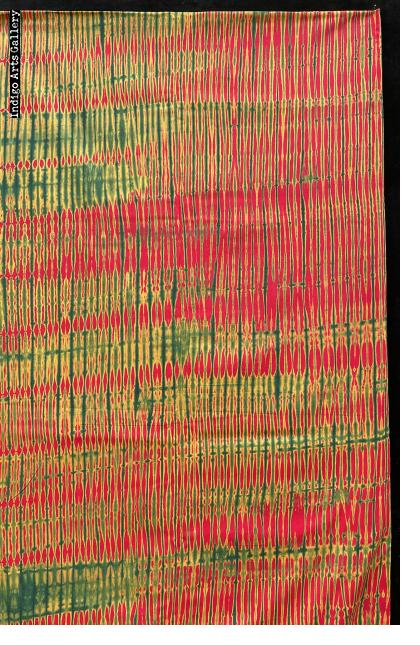

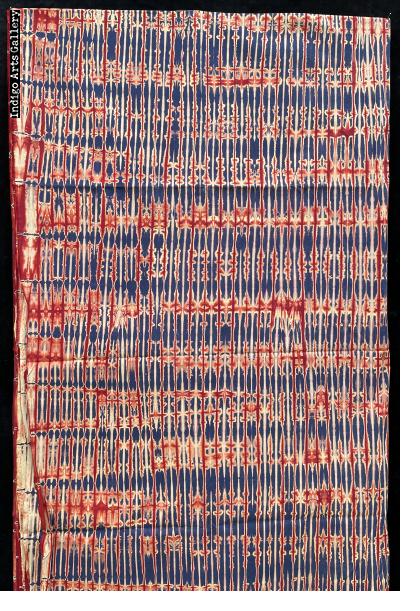

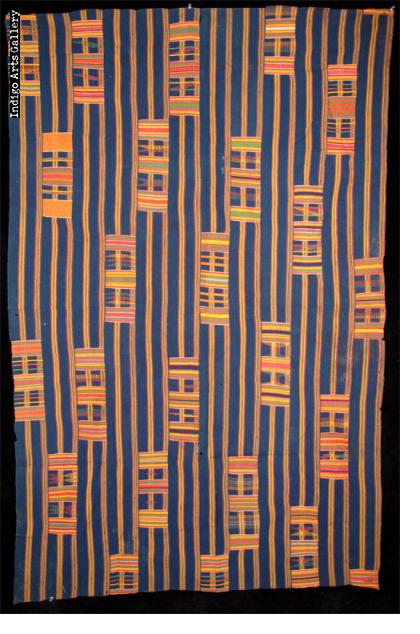

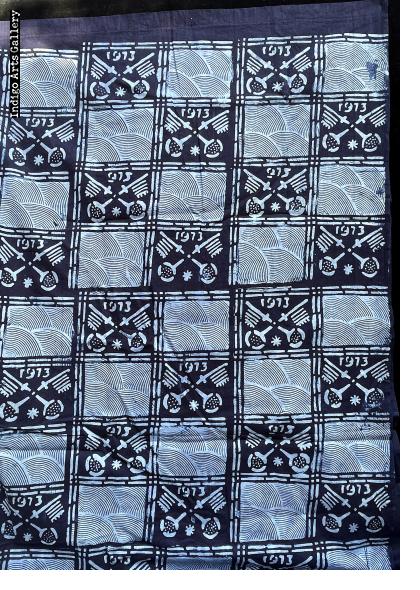

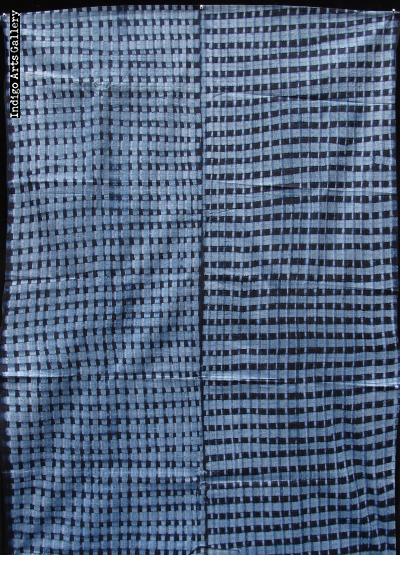

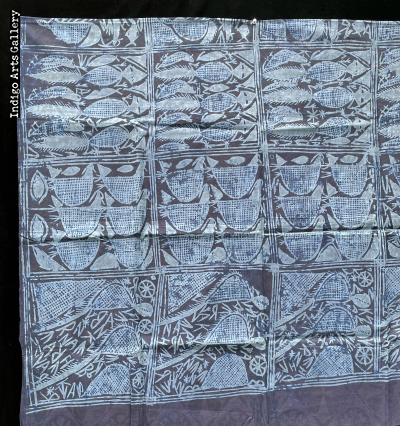

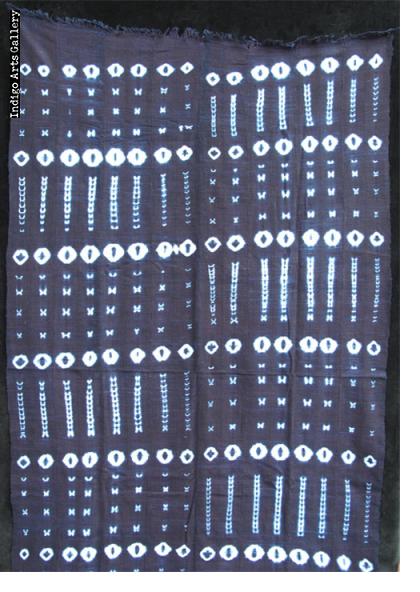

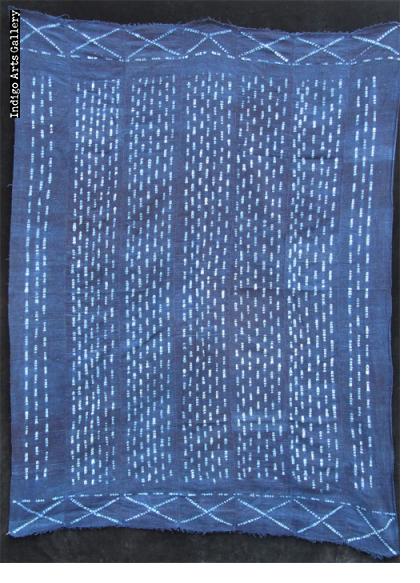

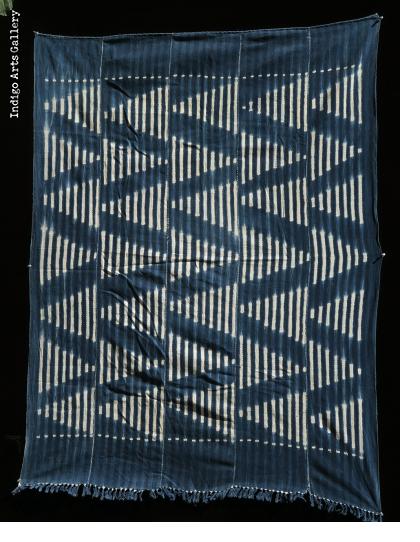

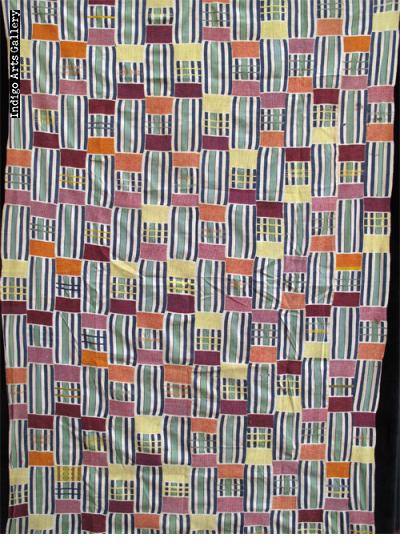

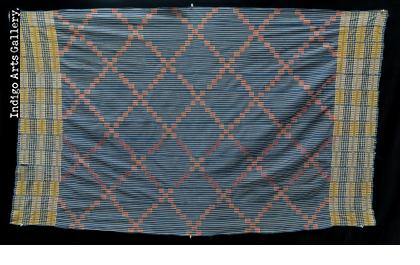

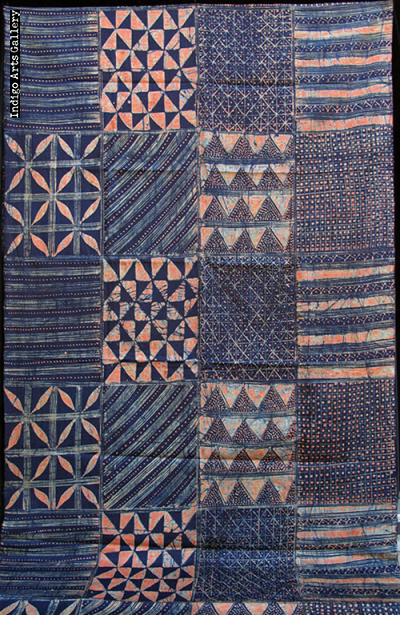

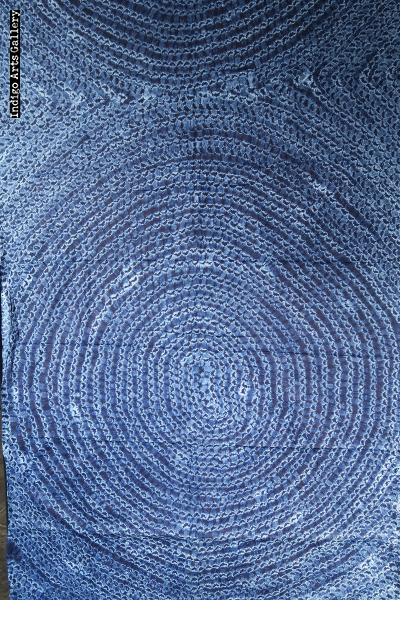

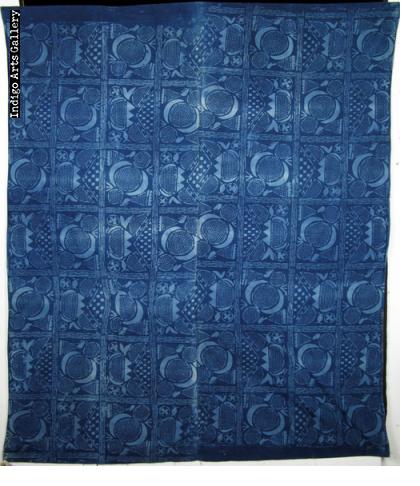

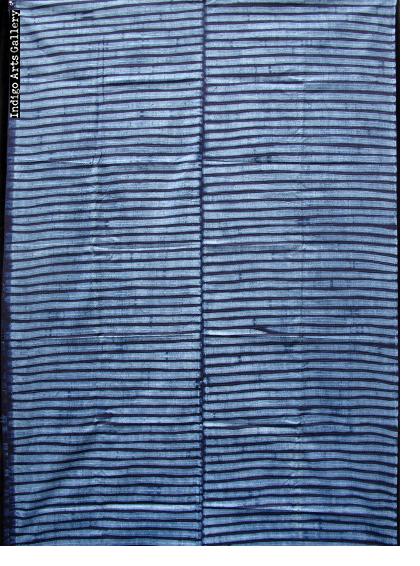

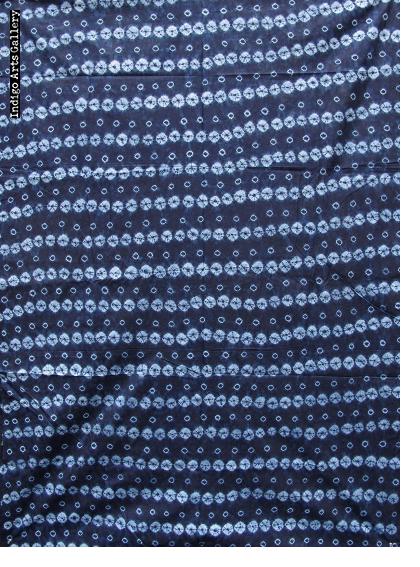

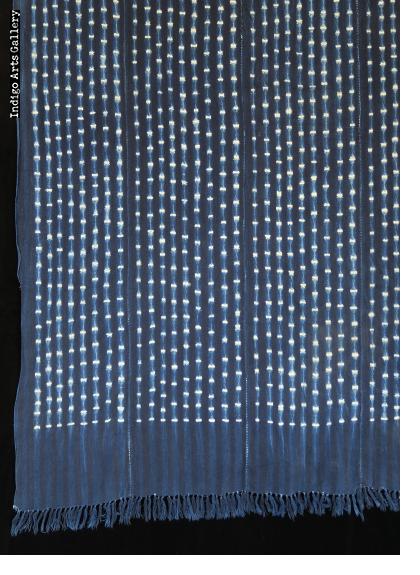

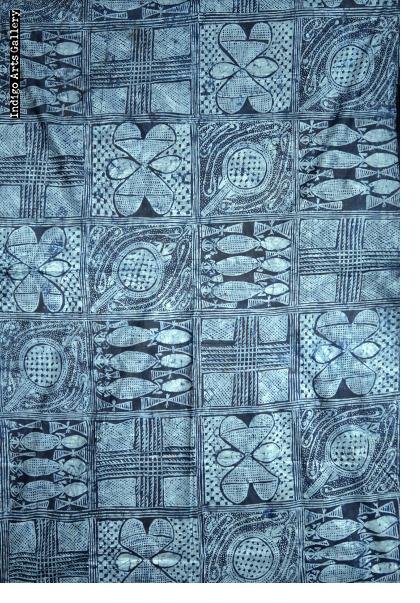

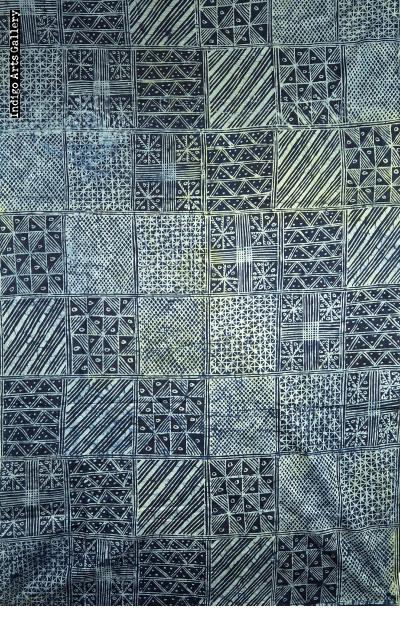

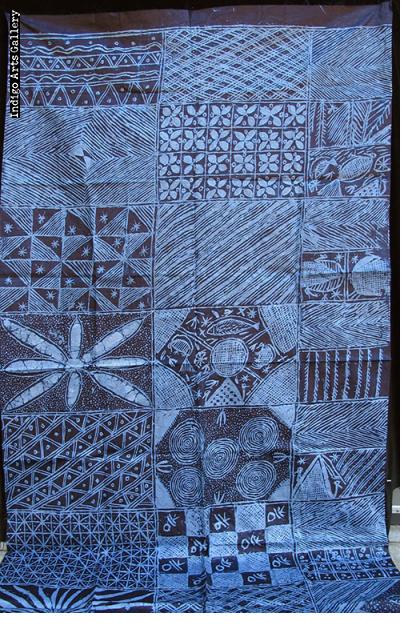

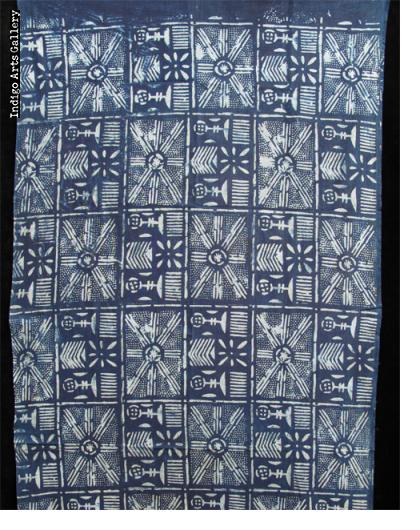

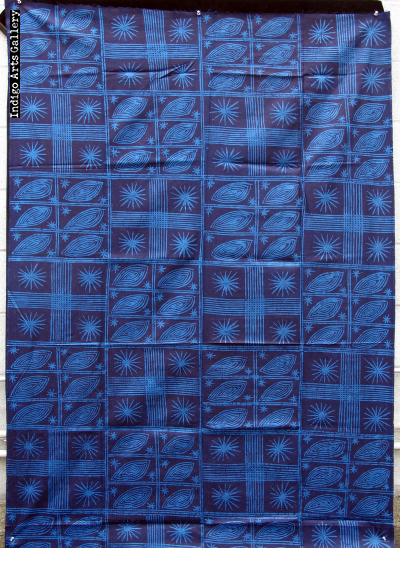

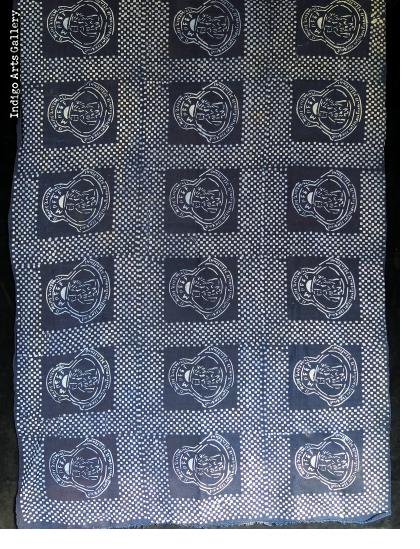

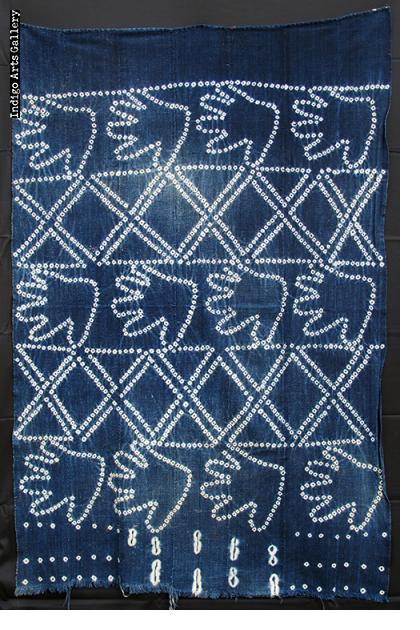

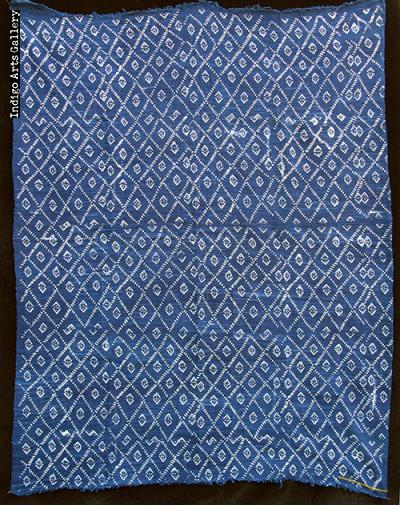

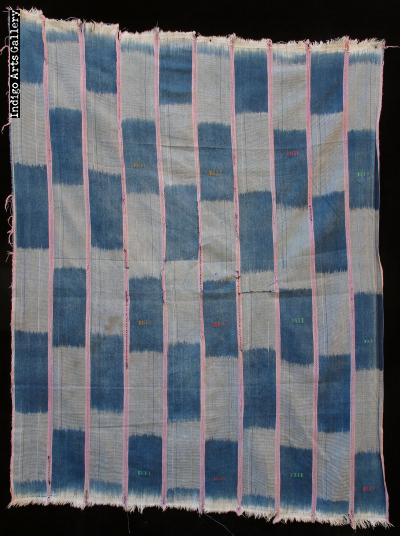

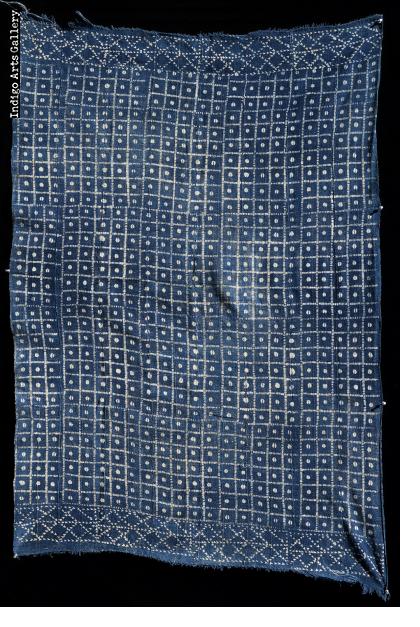

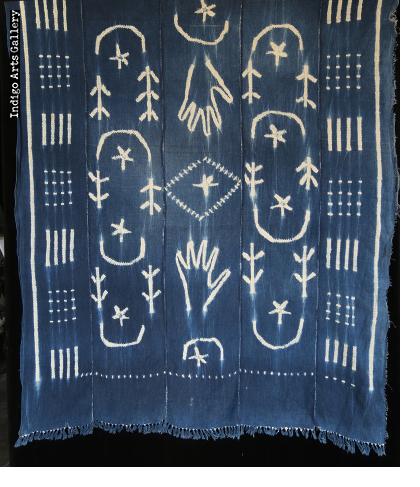

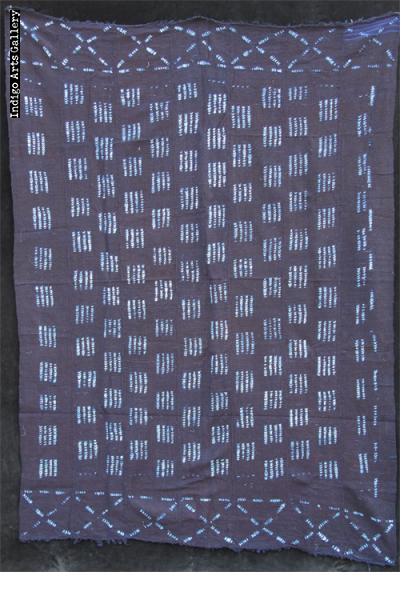

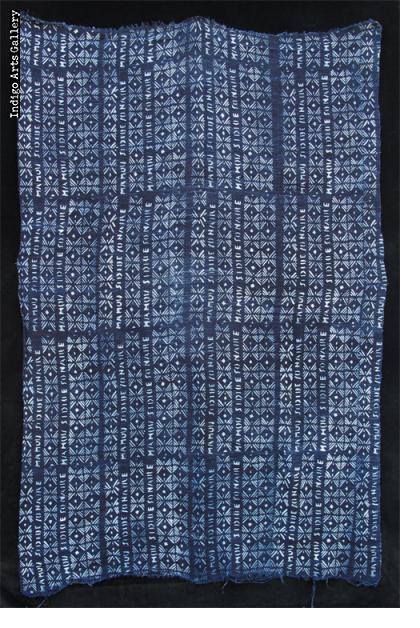

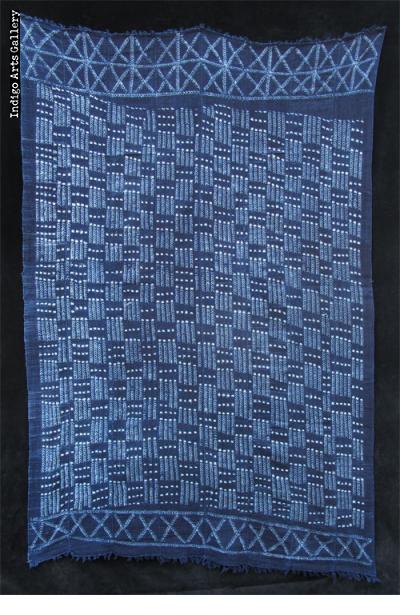

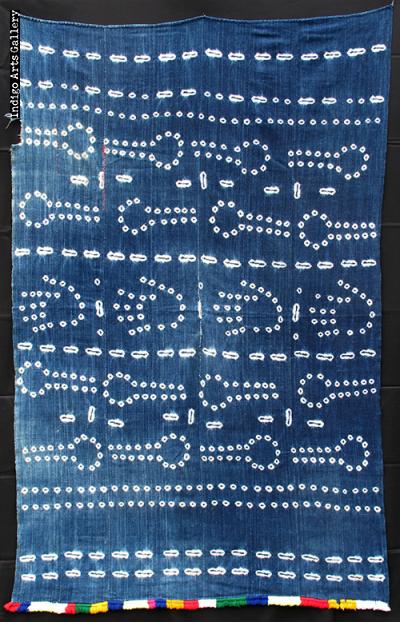

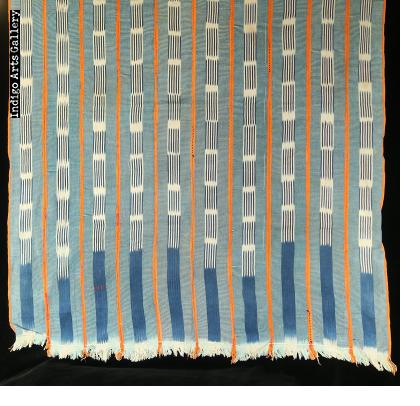

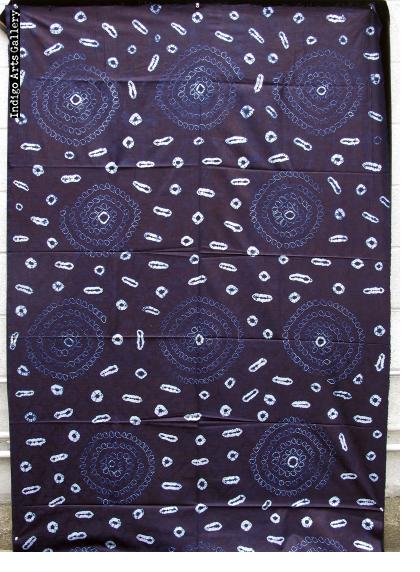

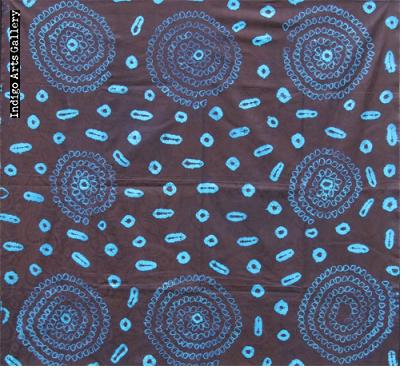

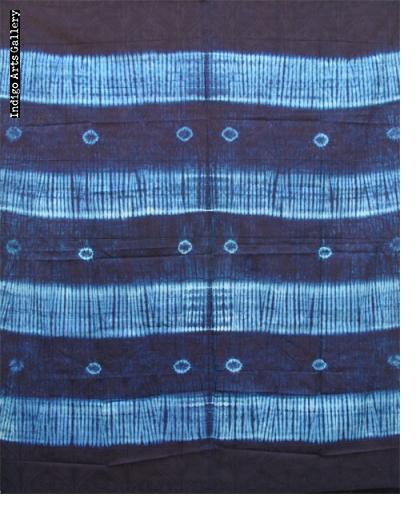

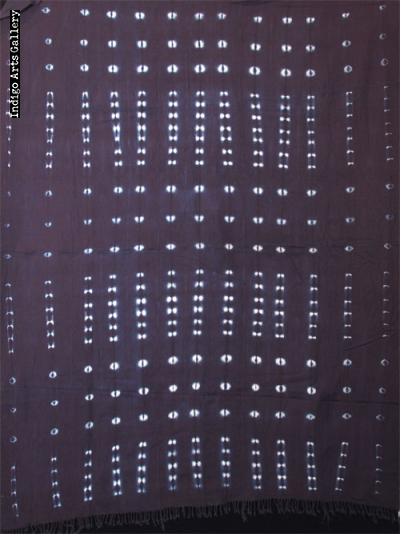

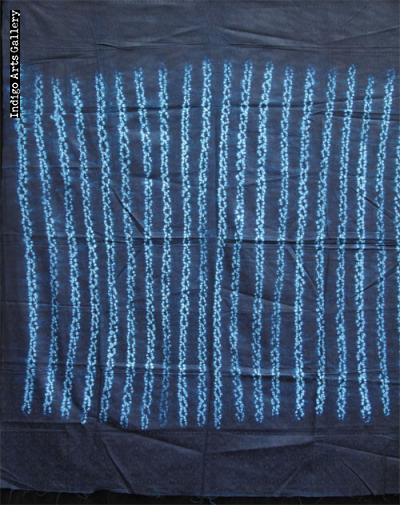

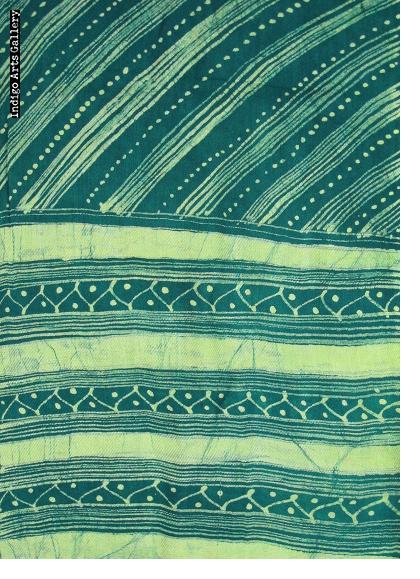

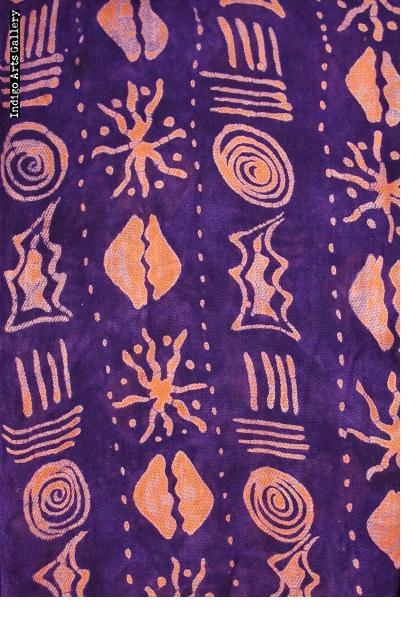

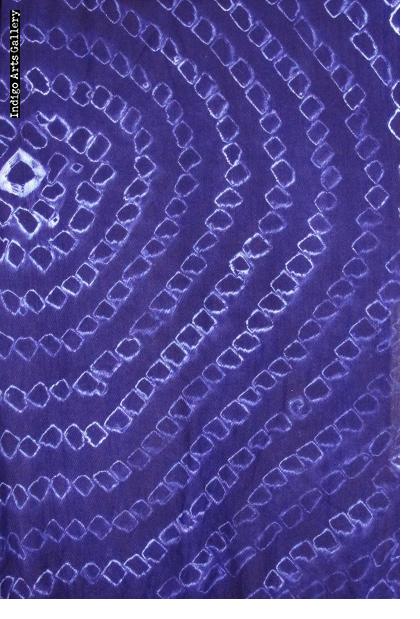

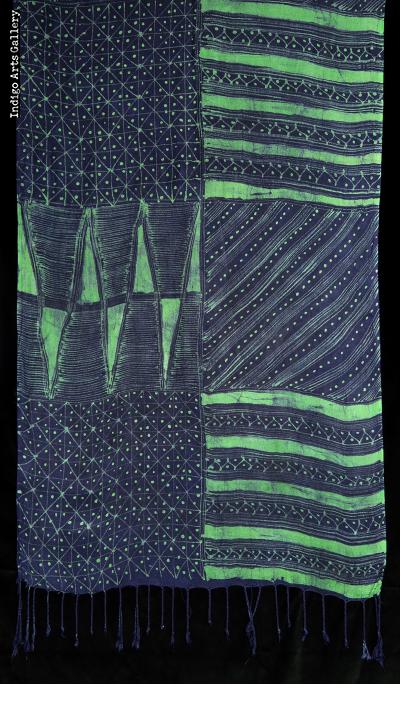

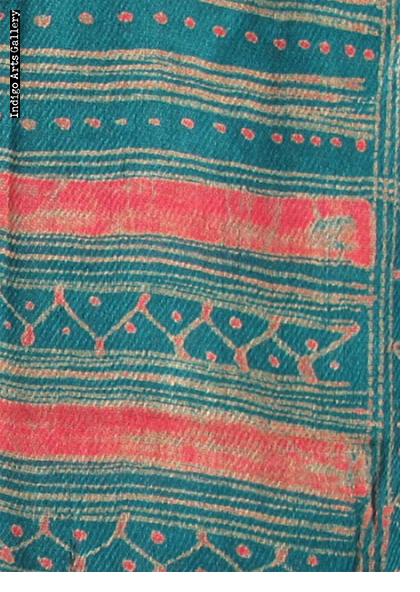

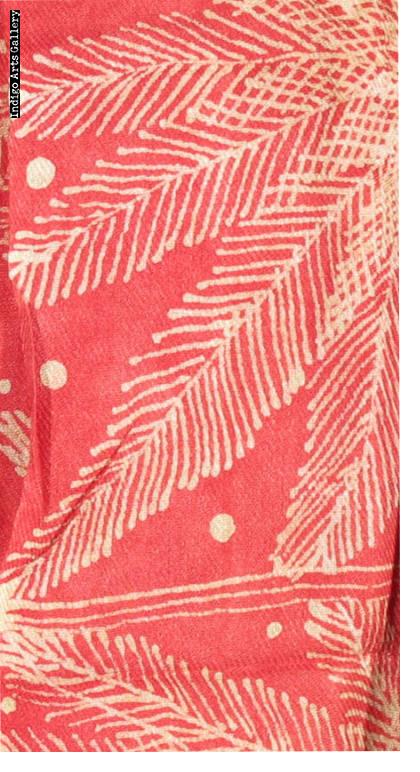

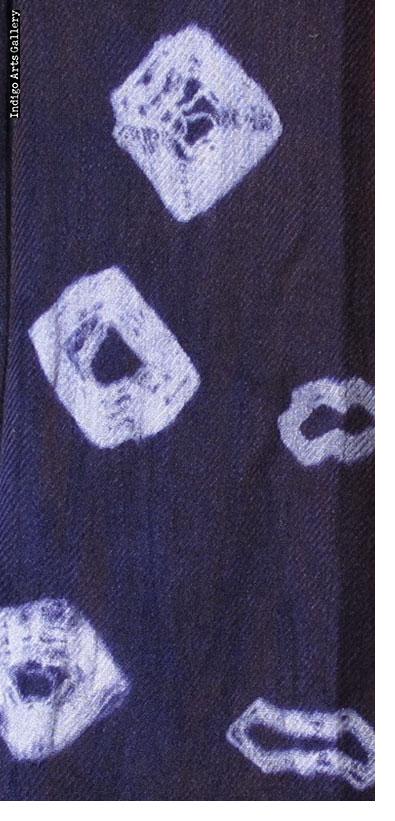

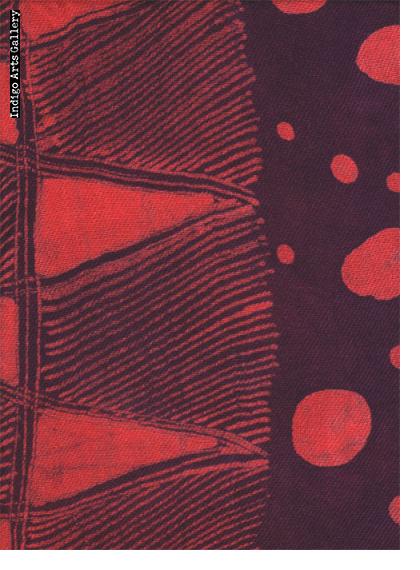

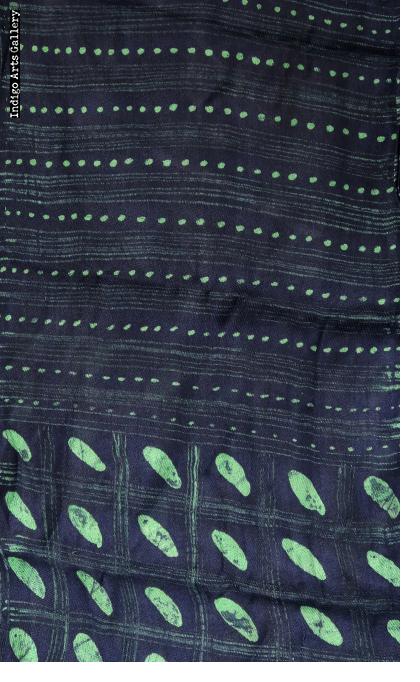

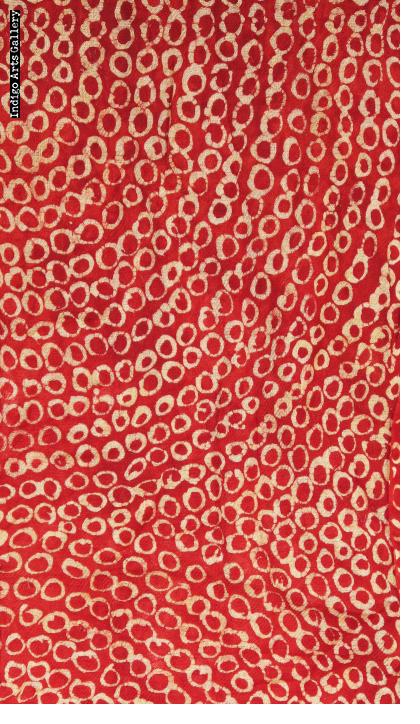

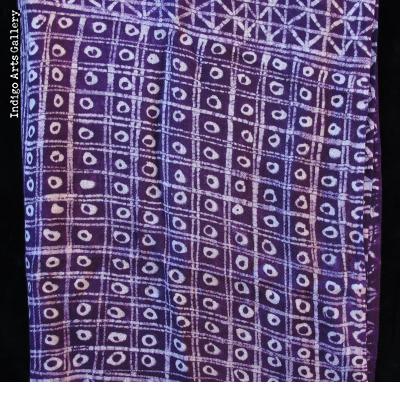

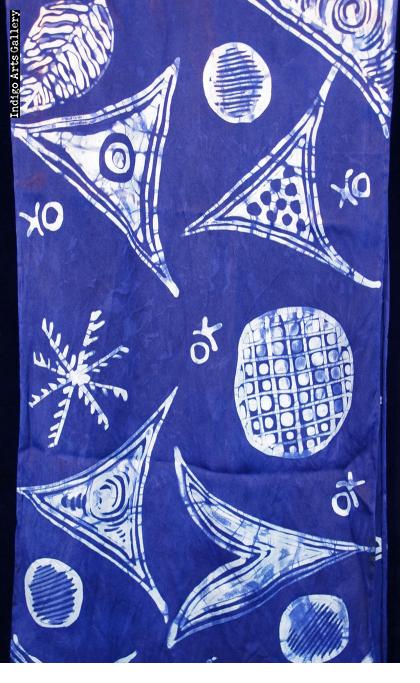

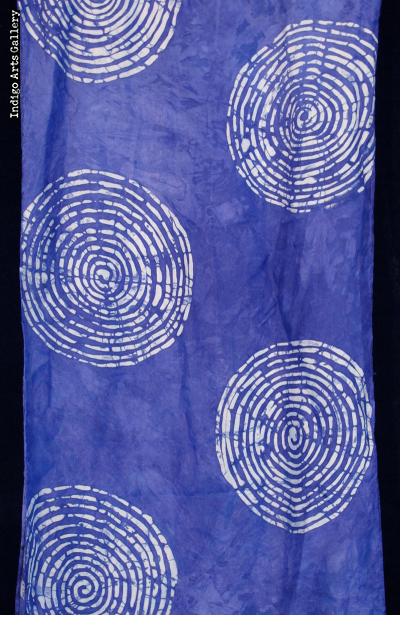

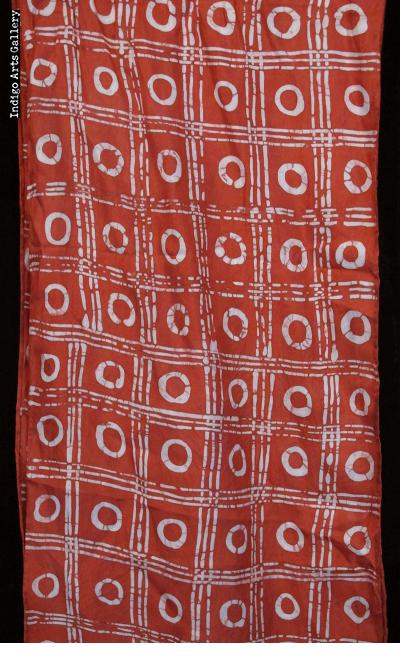

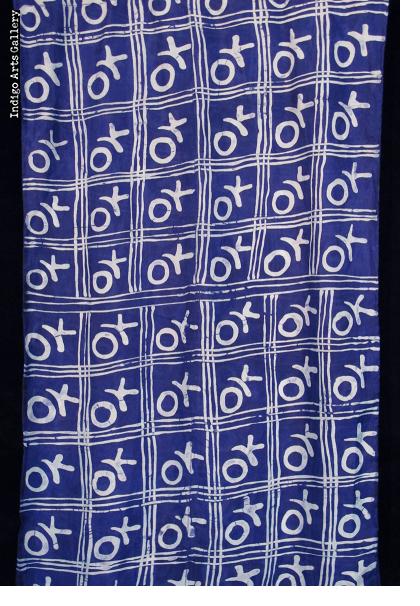

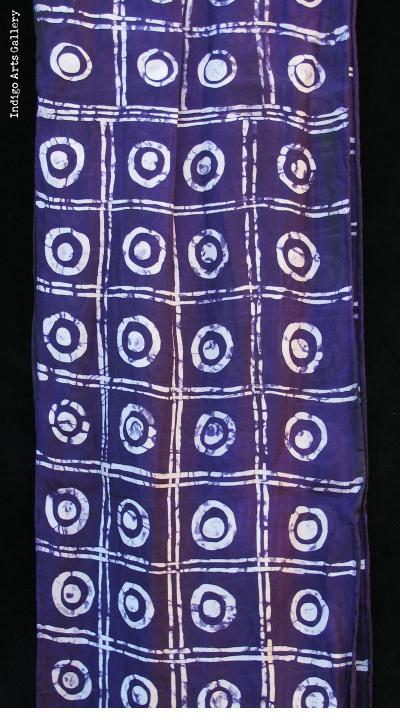

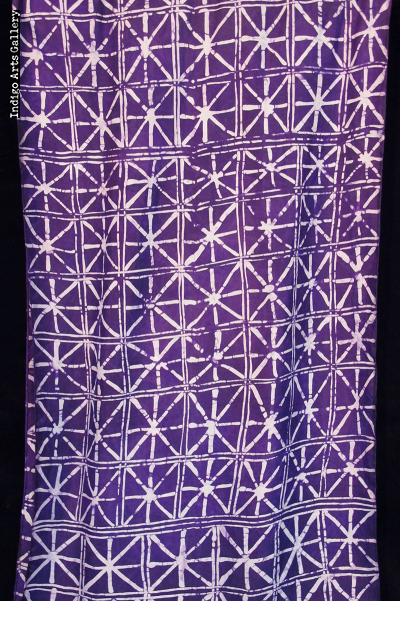

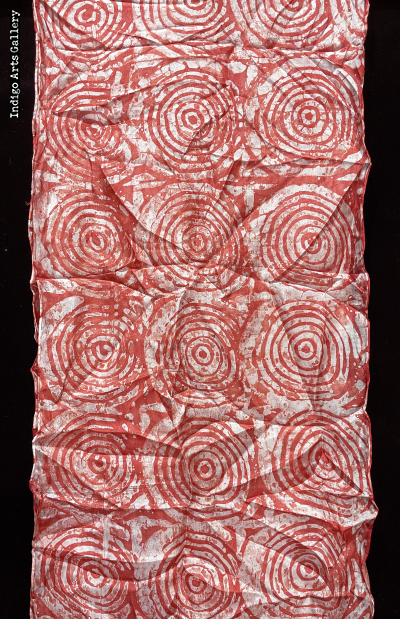

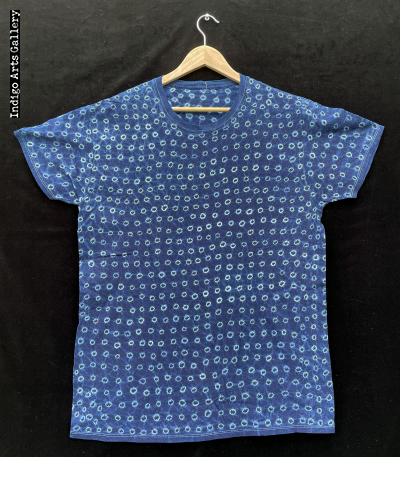

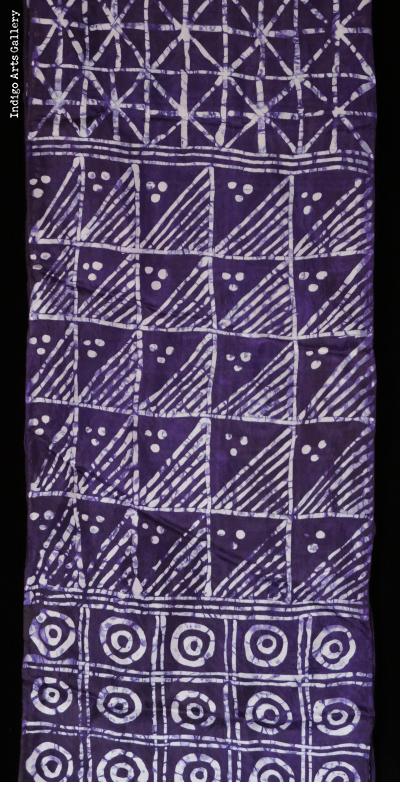

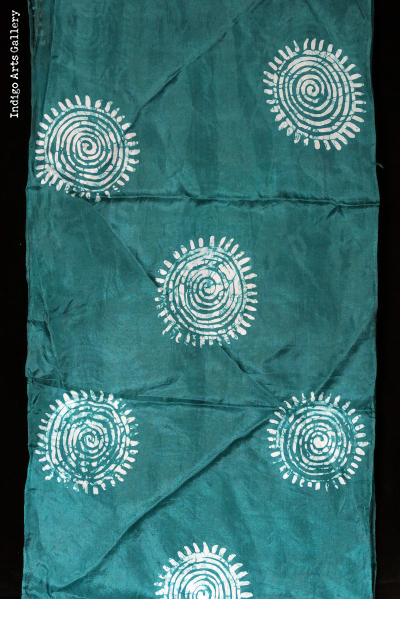

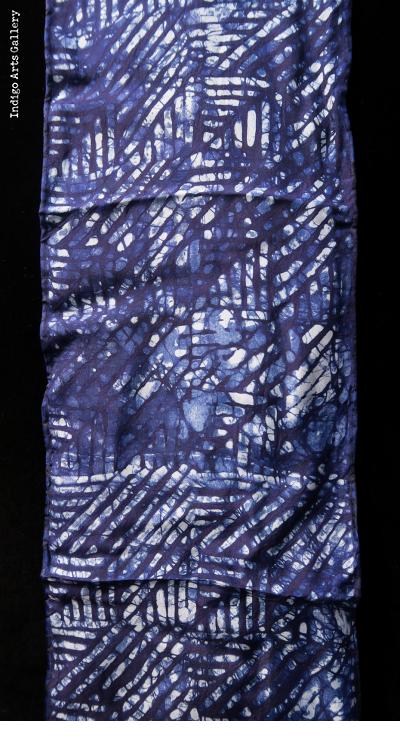

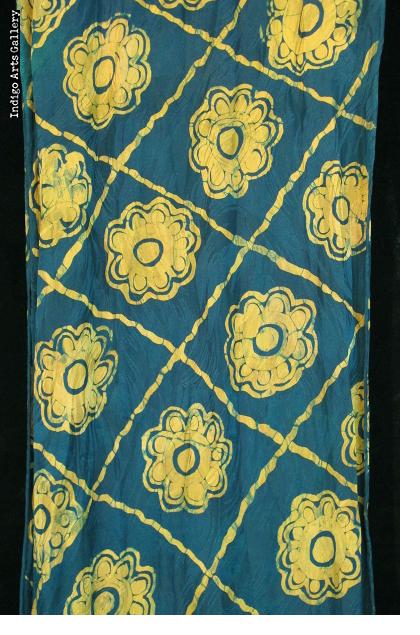

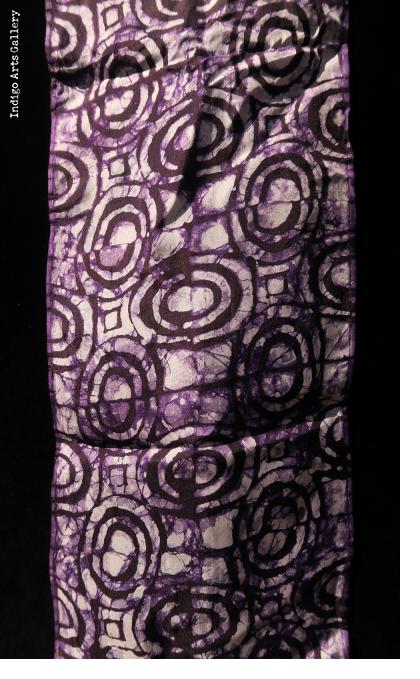

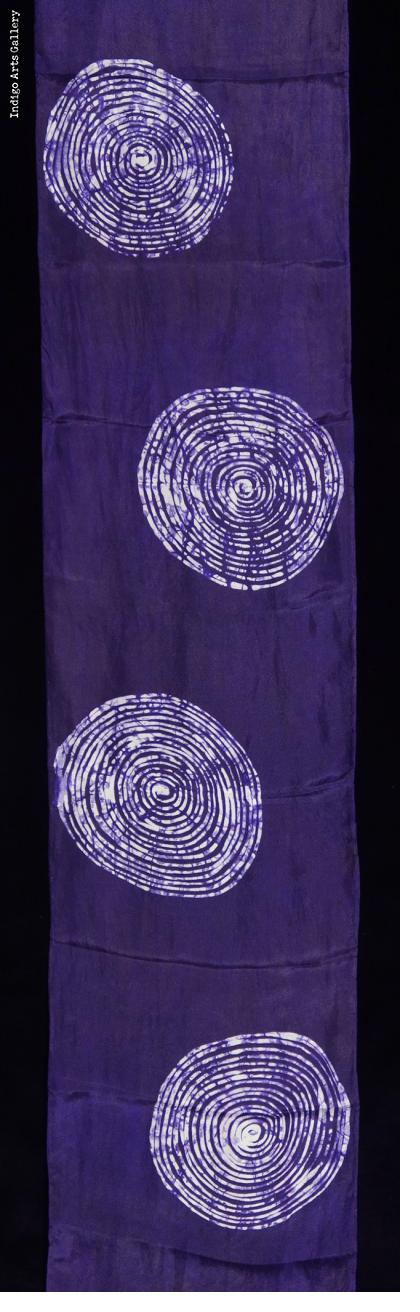

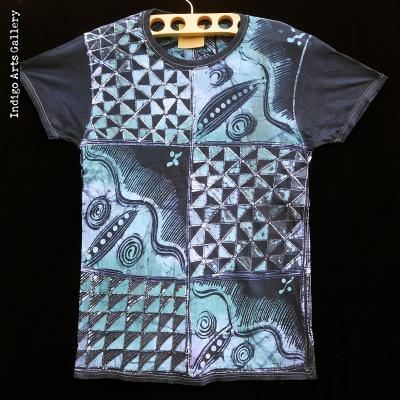

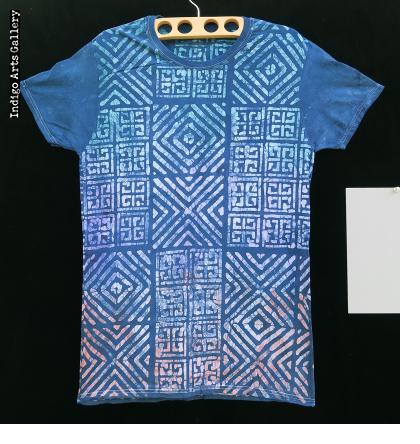

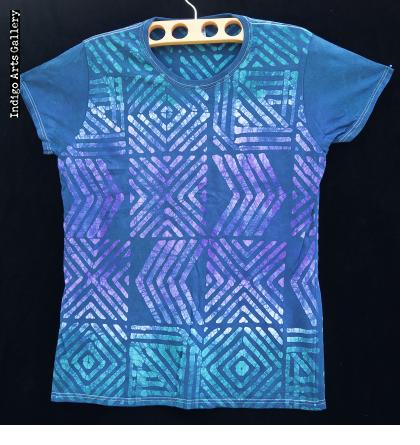

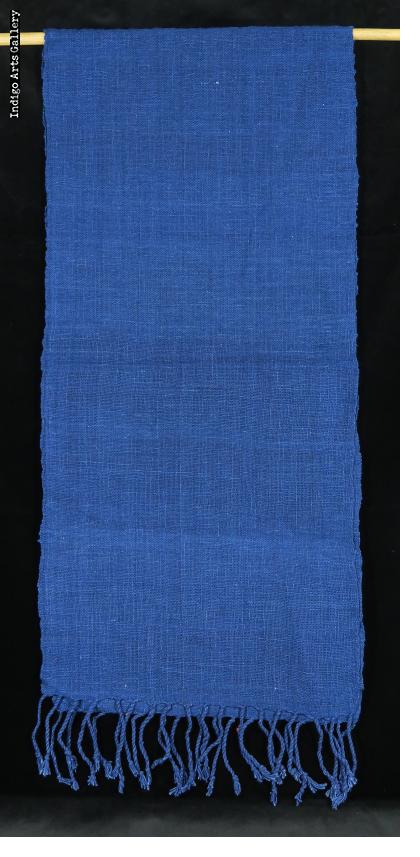

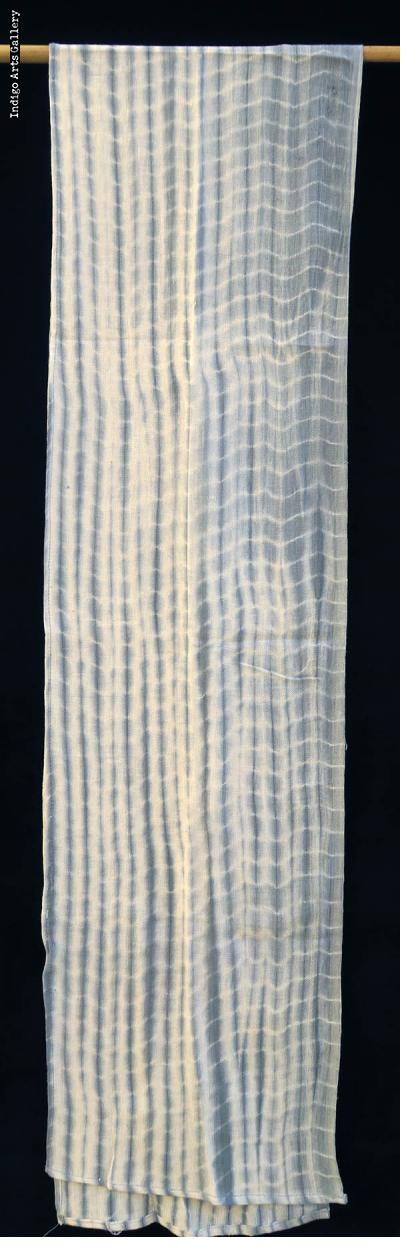

Indigo Arts Gallery celebrates Fiber Philadelphia 2012, and our 25th anniversary with an exhibit of the rich tradition of indigo textiles. Indigo at Indigo: Indigo-dyed Textiles from Africa focuses on natural indigo dyeing and weaving techniques in Africa, including the resist-dyed adire cloth of the Yoruba people of Nigeria, tie-dyed fabrics of the Yoruba and the Bamana people of Mali, and strip-woven indigo kente cloth from the Ewe of Ghana and Togo. A sampling of indigo textiles from other African, Asian and Latin American traditions will also be on display. The exhibit also featured a demonstration of cassava-starch resist and tie-dyeing techniques by master Yoruba artist Gasali Adeyemo.

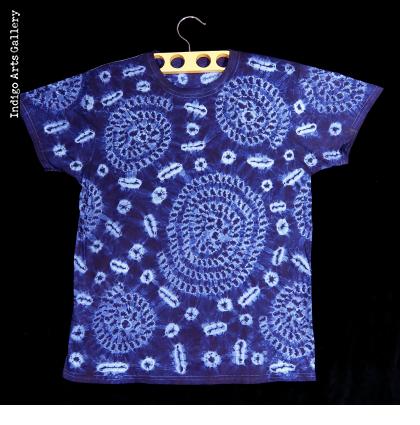

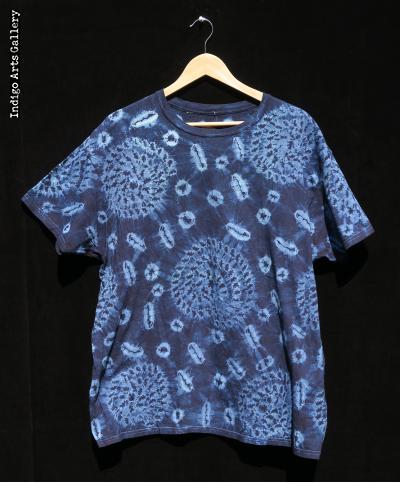

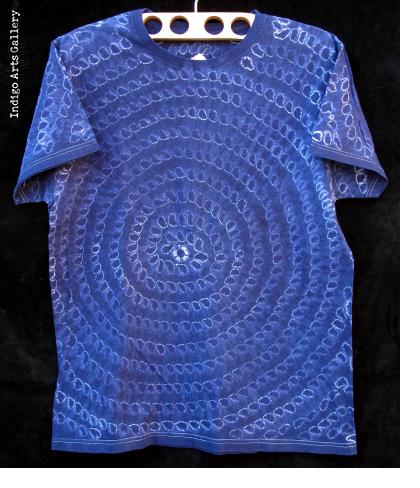

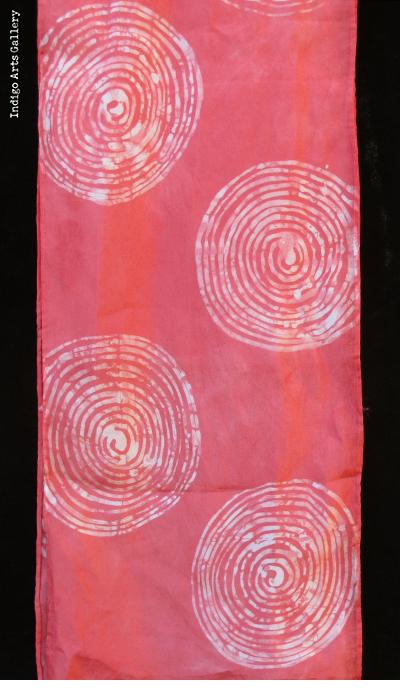

Gasali Adeyemo

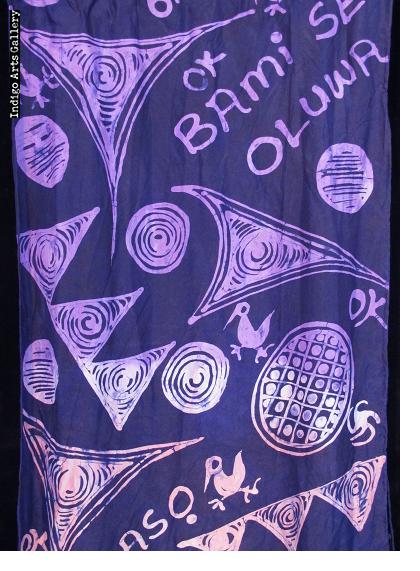

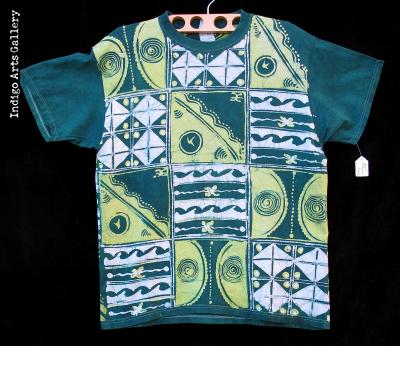

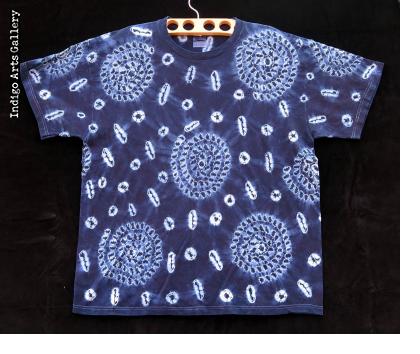

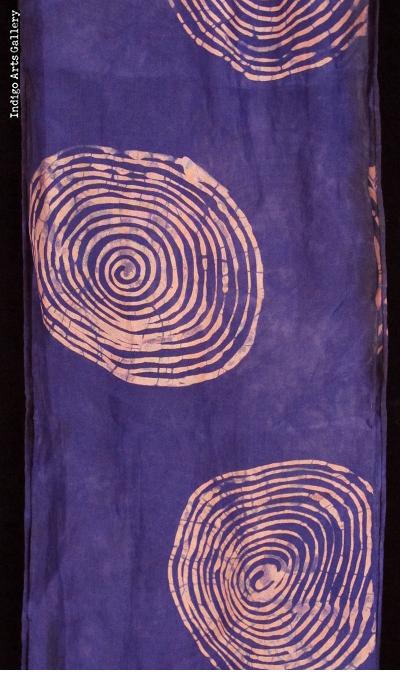

Born in the small village of Offatedo in Osun State, Nigeria, Gasali Adeyemo showed an early skill for drawing. He found time between work in the fields to sketch portraits of guests at funerals, weddings and naming ceremonies. In 1990 he began studying at the Nike Center for Arts and Culture (founded by Nike Okundaye, the former wife of the late artist Twins Seven-Seven) in Oshogbo, Nigeria. There he mastered the arts of indigo dyeing, batik, embroidery and applique. After two years of study he stayed on to teach for another four years. A 1995 exhibit of his artwork in Bayreuth, Germany led to a number of exhibits abroad. In 1996 he exhibited his work in Iowa, and he subsequently settled in the United States. Today he lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico and exhibits and conducts workshops all over the country. There is an excellent interview with Gasali in the Fall 2011 issue of Hand/Eye magazine , #06 Global Color. The magazine can be ordered from us or the Hand/Eye magazine website.

Mr. Adeyemo demonstrated his techniques at Indigo Arts on the opening day, Sat. March 3rd (2 to 8pm). On Sunday, March 4th (12 to 3pm) he conducted an indigo dyeing workshop in the building.

A review of the exhibit appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

A Short History of Indigo

Indigo, a vibrant deep-blue hue, is derived from a plant family called indigofera tinctoria. The dye process requires boiling or steeping the leaves of the Indigo plants and then a fermentation of the brew. Once the fabric is dipped into the dye and lifted into the air it almost magically turns blue. Each region has its own recipes and techniques, but in most cases it requires many successive dippings to attain the intense blue color we associate with indigo.

Indigo was grown in India, Indonesia, China, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Guatemala, Haiti, Peru, and Africa. Each country has it's own history and traditions of dyeing with Indigo. When indigo was first brought to Europe it was an instant sensation, largely replacing the much weaker blue hue of woad. By the 17th century it had become a precious trading commodity, a "blue gold" which brought with it both great wealth and intense suffering. Ships called "East Indiamen" crossed the seas laden with silks, spices and Indigo.

In the new world indigo was by far the most valuable crop of the slave economy. It was largely because of the cultivatiion of indigo by African slaves that Haiti became the most valuable colony in the New World. In the mid-18th century indigo cultivation, also using slaves labor, was brought to South Carolina. In India, the British colonial powers imposed indigo cultivation at the expense of food production to the extent that the peasants starved. This led to the "Blue Mutiny" of 1861, in which the Bengali peasants rose up against the planters and refused to grow indigo.

In the United States the current cachet of indigo dates to 1873 when San Francisco merchant Levi Strauss and tailor Jacob Davis first fashioned sturdy trousers for miners by reinforcing indigo-dyed denim with metal rivets. The rest is history, as they say. The invention of far cheaper aniline dyes in 1856 ultimately supplanted natural indigo dye in the world marketplace. Though Levi Strauss & Co. stopped dyeing their jeans with natural indigo over a century ago, indigo, like blue jeans has persisted as a symbol of "cool" worldwide.

Large scale indigo plantations died out in the 20th century, but small-scale cultivation has persisted in the parts of the globe where indigo dyeing and weaving are still treasured. Traditional indigo artisans in locales as diverse as Mali, Nigeria, India and Japan have preserved old techniques. Fortunately there are centers where the art form is being passed on to new generations. One such center is the Nike Center for Arts and Culture in Oshogbo, Nigeria, where our guest artist, Gasali Adeyemo learned his craft.

Two recent documents recount the story of indigo, Catherine E. McKinley's book Indigo: In Search of the Color that Seduced the World (2011), and Mary Lance’s documentary film: Blue Alchemy : Stories of Indigo (2011).