Retablos from Ayacucho and Shipibo/Conibo Textiles from the Amazon Basin

Show dates: March 9, 2017 through September 30, 2017

Opening reception: Second Thursday, March 9, 6 to 9pm.

Gallery Hours: Wednesday through Saturday, 12 to 6pm.

Andes/Amazon: Two Worlds in Peruvian Folk Art looks at two distinct contemporary folk arts in two regions of Peru: the portable retablo shrines, originally from highland Ayacucho and the patterned textiles and ceramics of the Shipibo/Conibo peoples of the Amazon basin. Both are arts in transition. From deep traditional roots they are adapting to new materials and influences, and being both changed and enriched in the process.

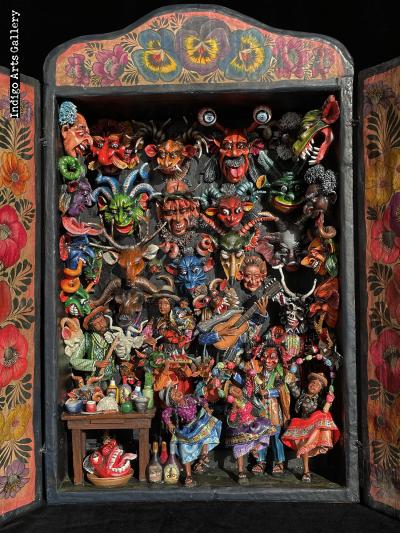

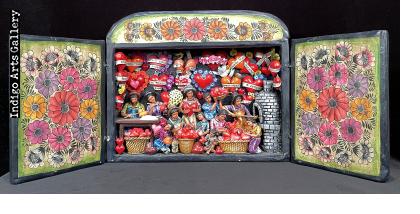

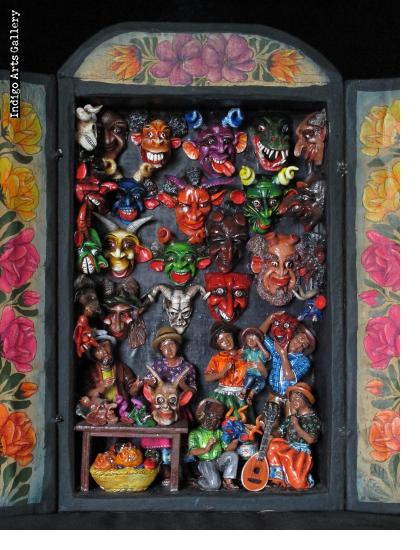

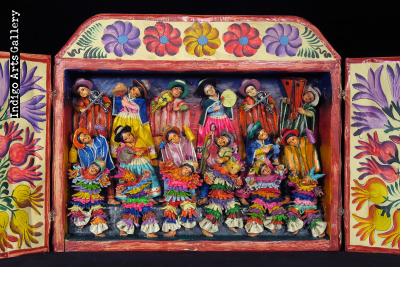

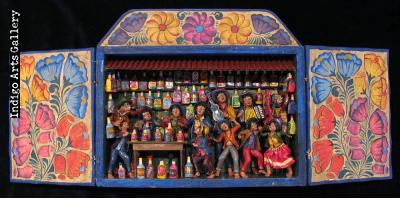

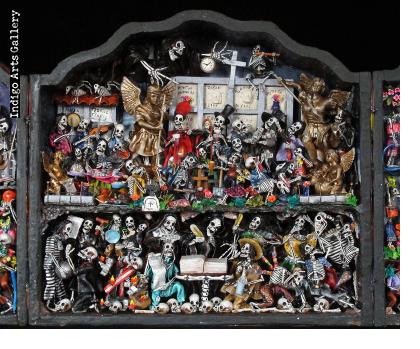

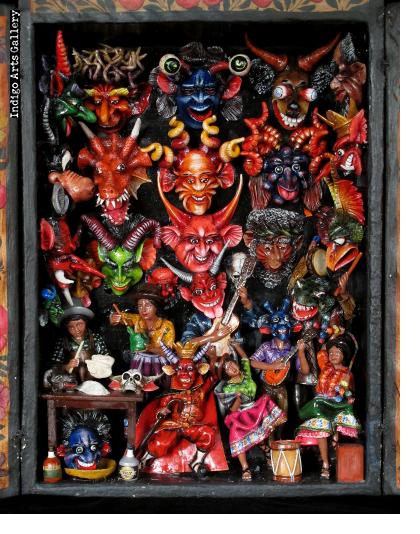

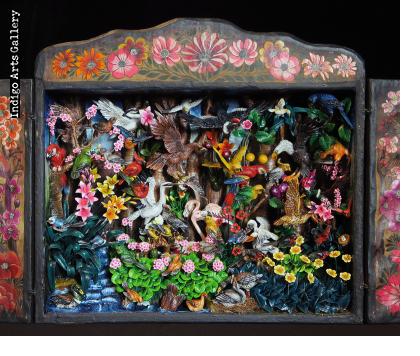

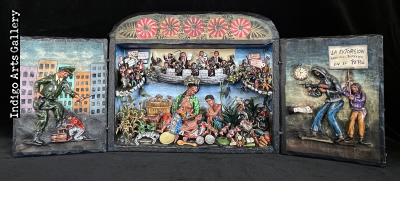

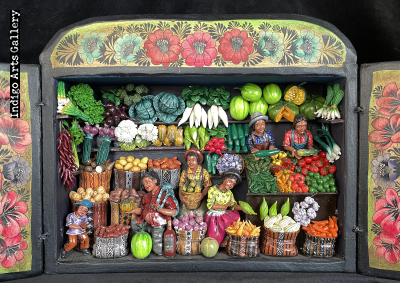

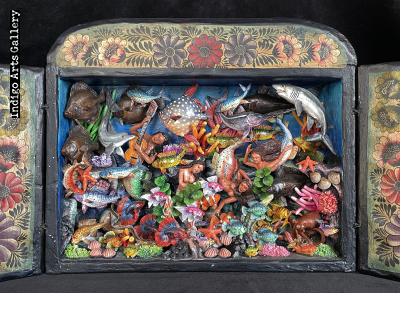

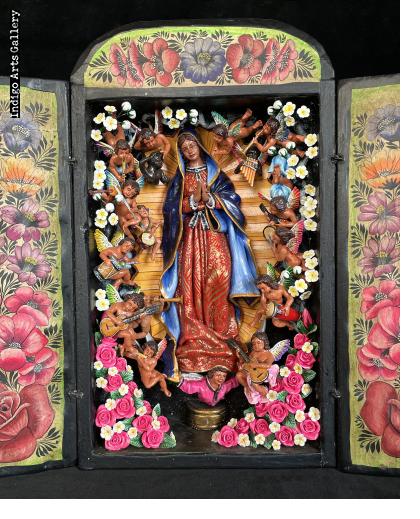

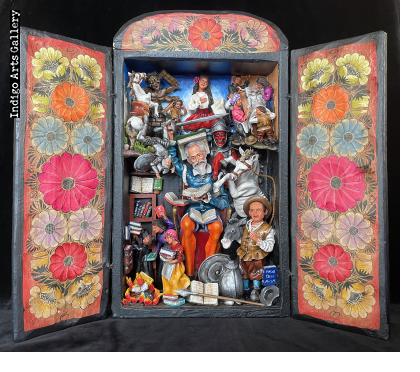

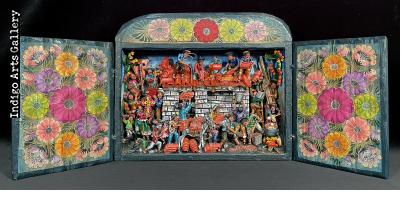

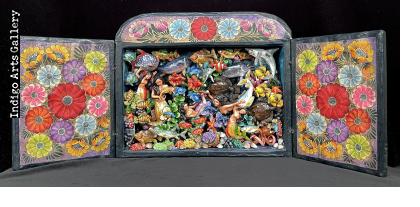

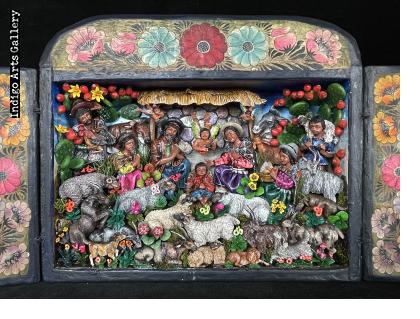

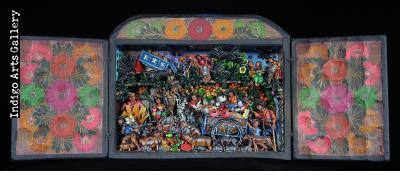

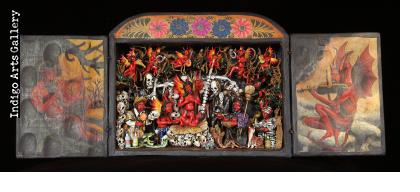

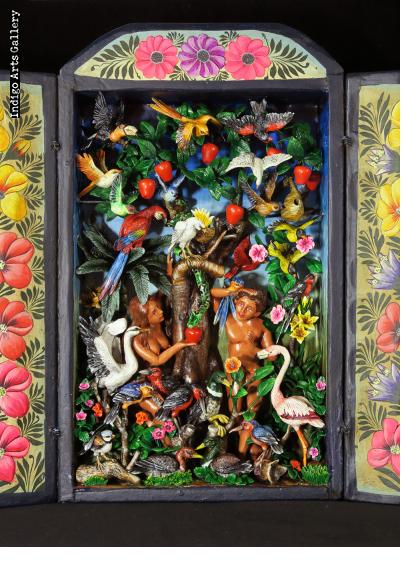

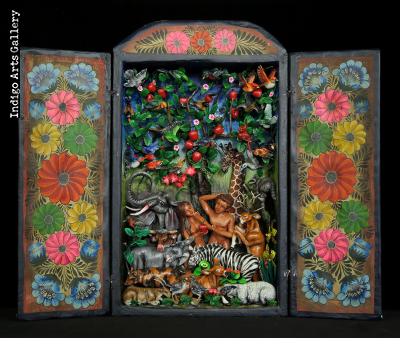

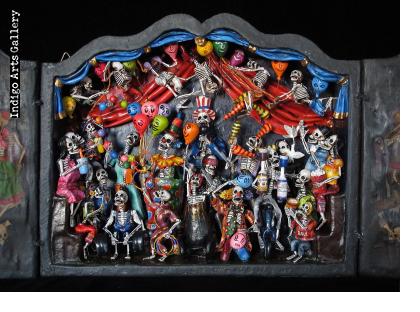

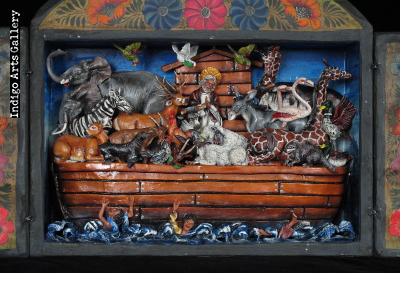

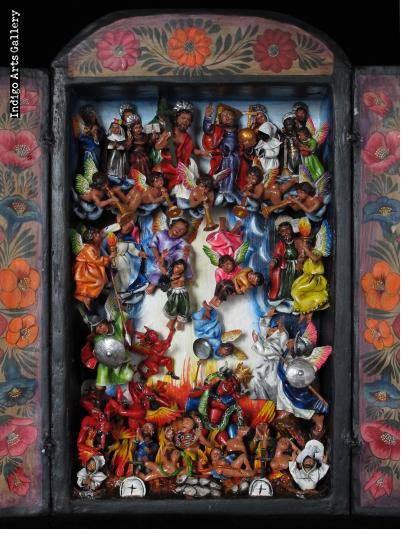

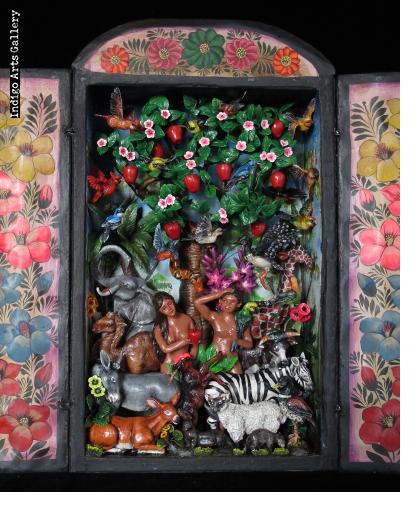

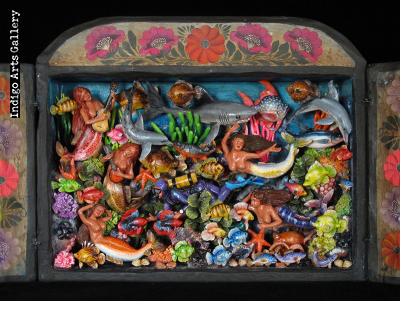

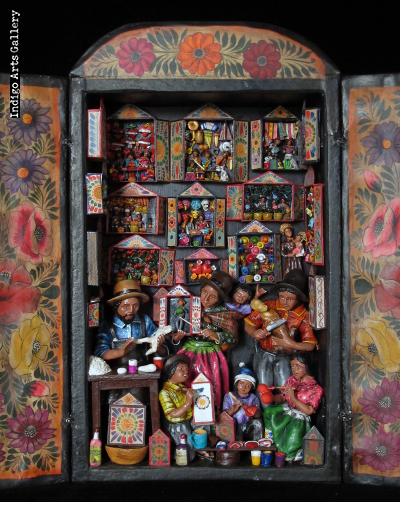

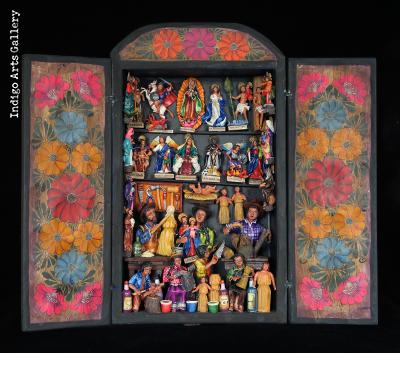

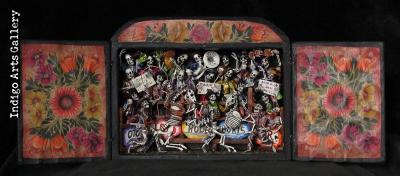

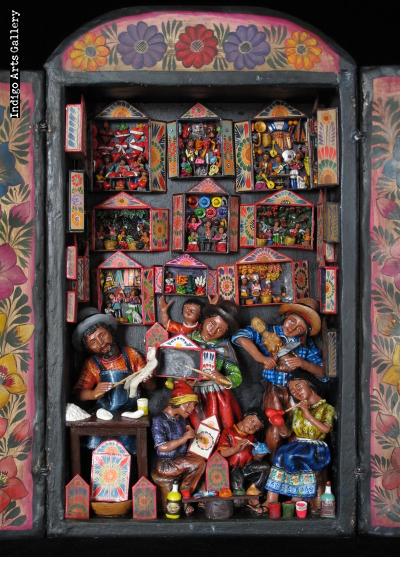

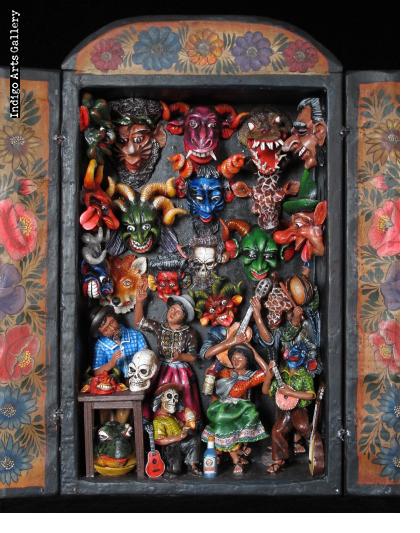

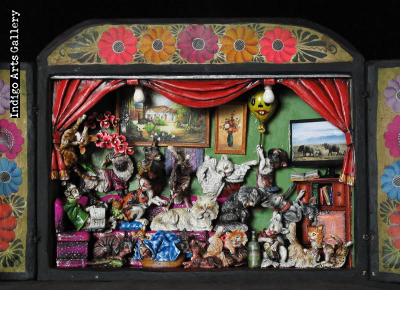

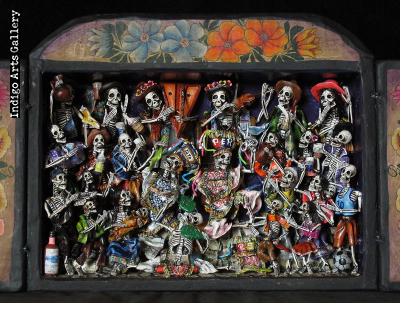

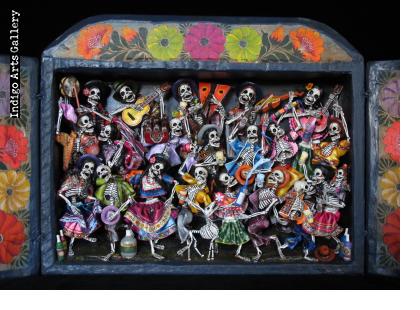

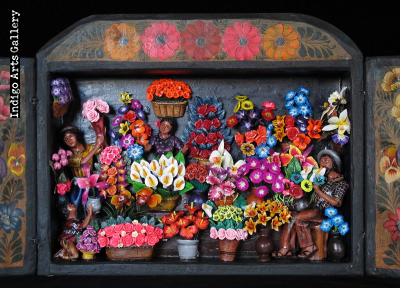

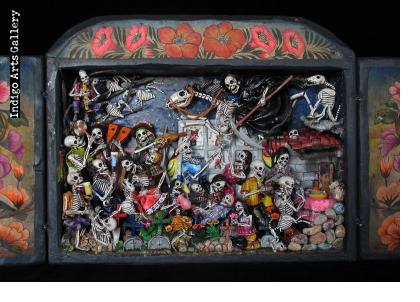

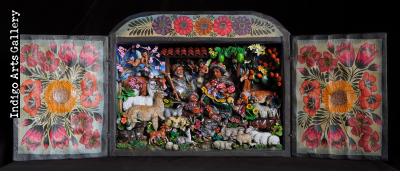

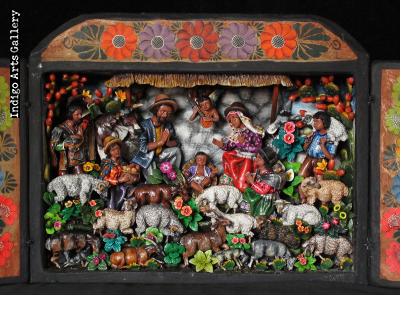

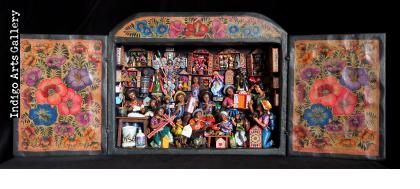

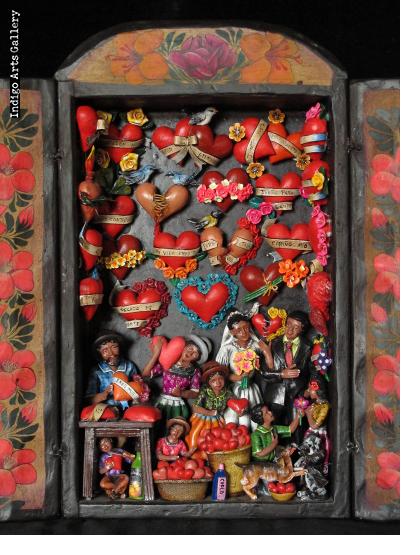

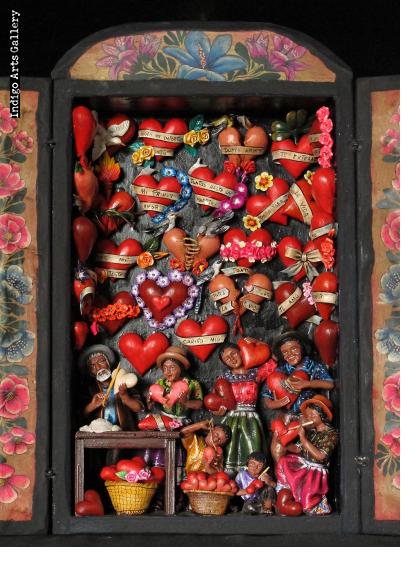

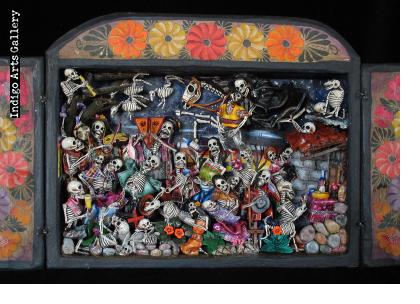

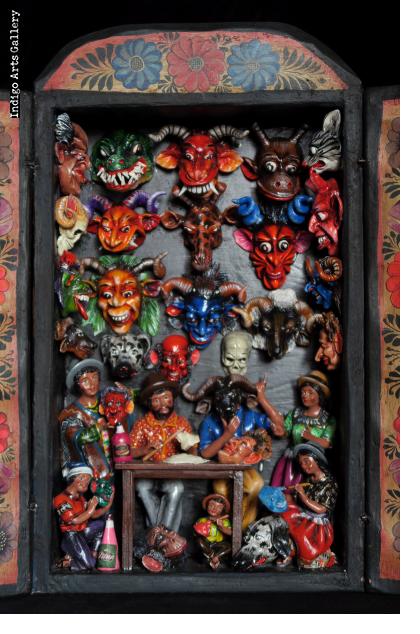

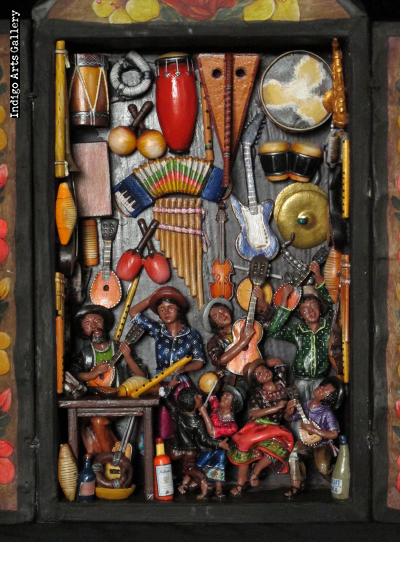

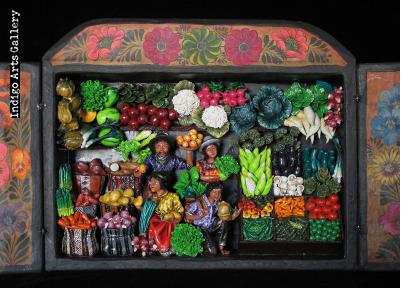

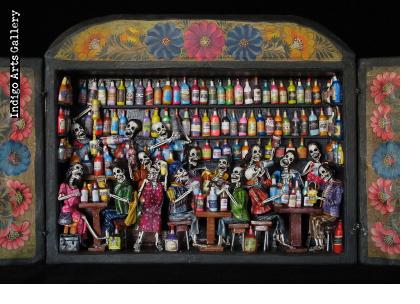

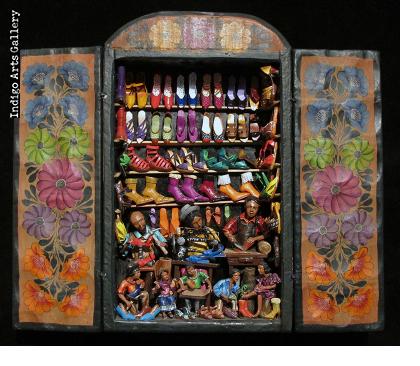

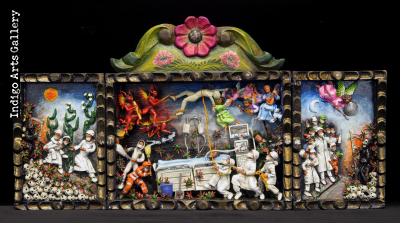

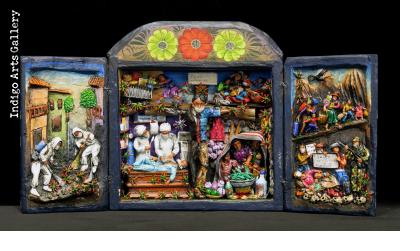

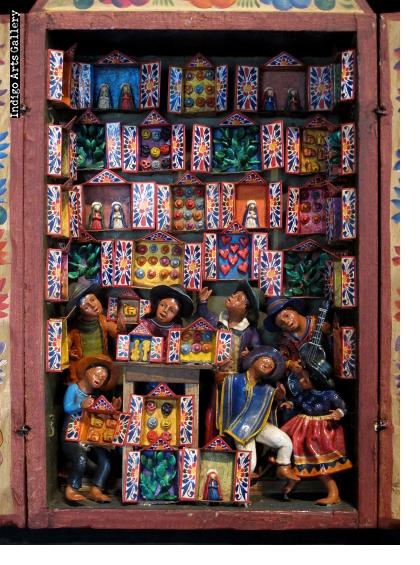

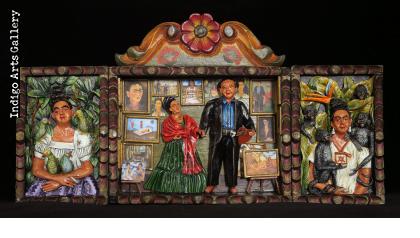

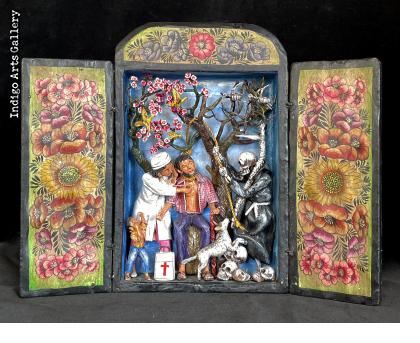

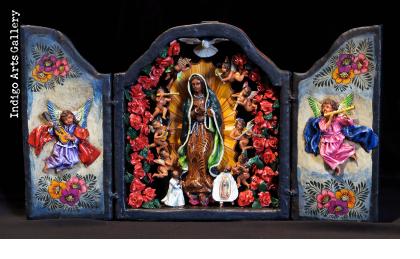

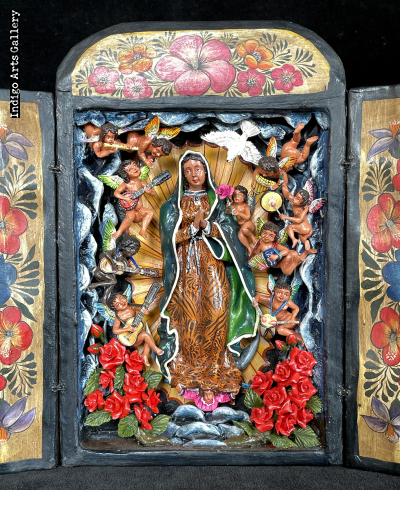

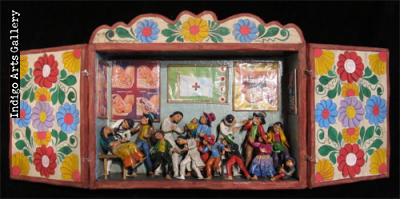

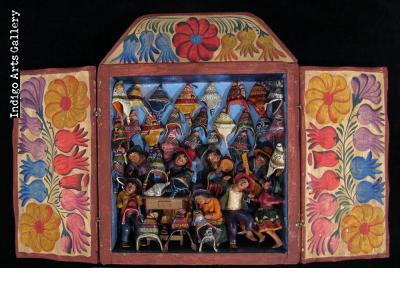

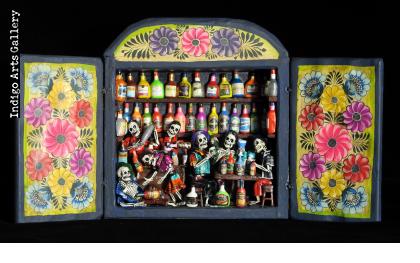

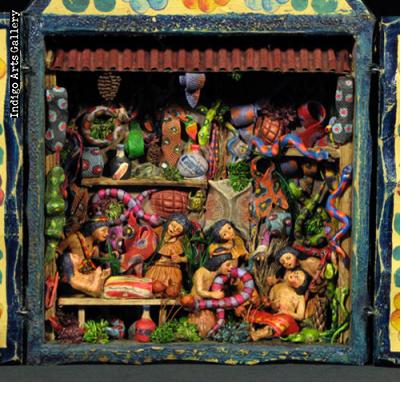

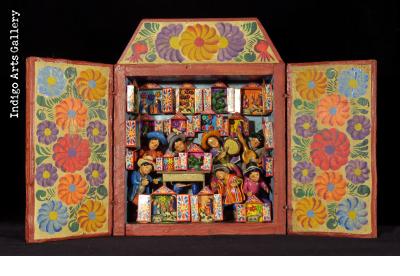

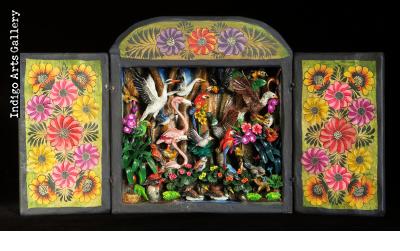

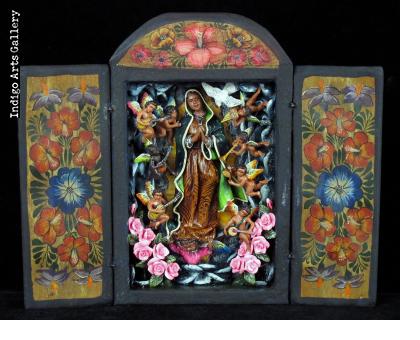

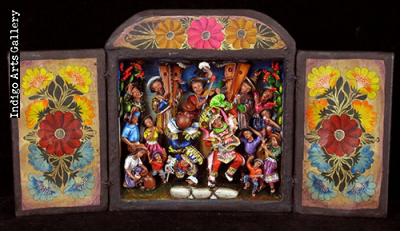

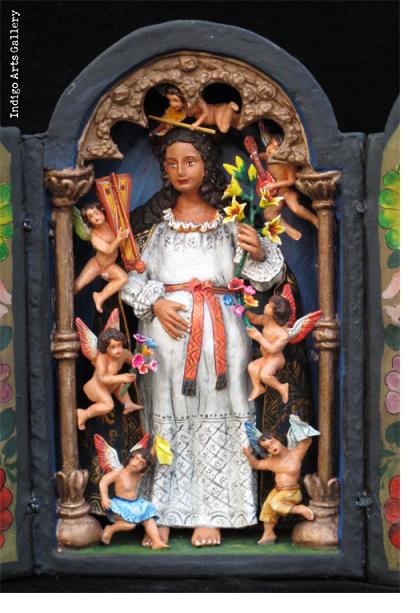

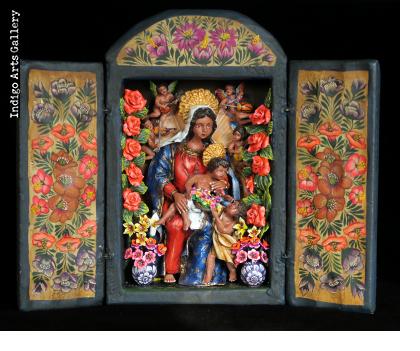

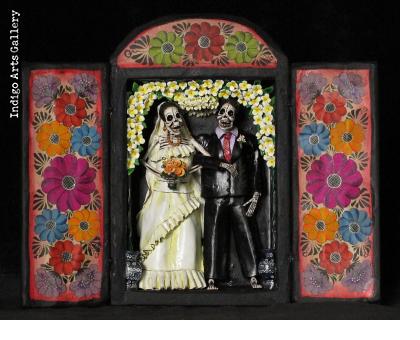

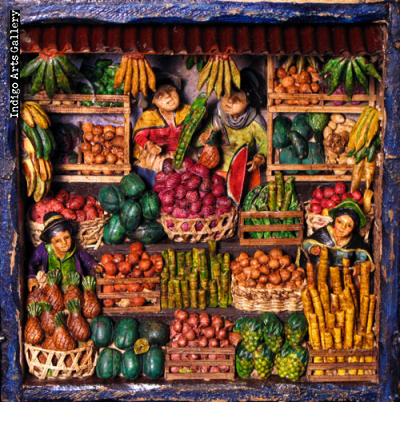

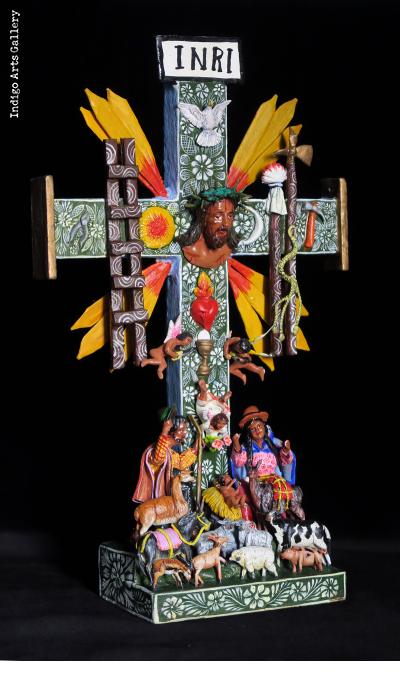

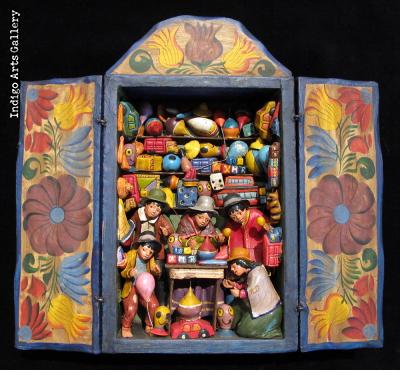

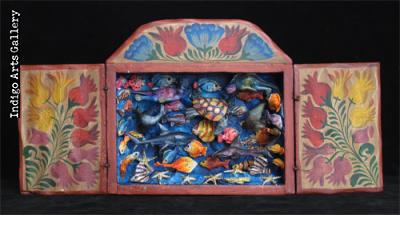

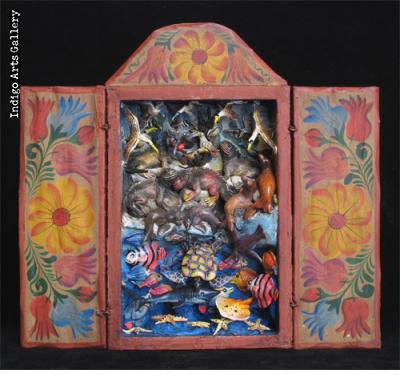

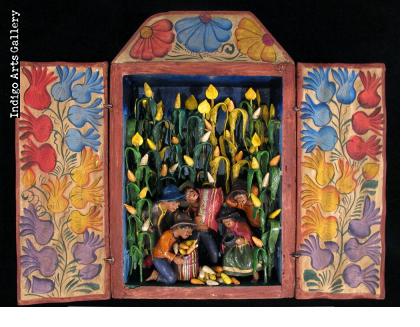

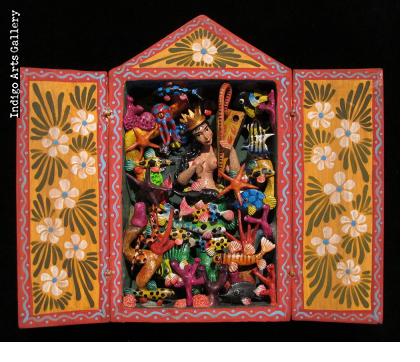

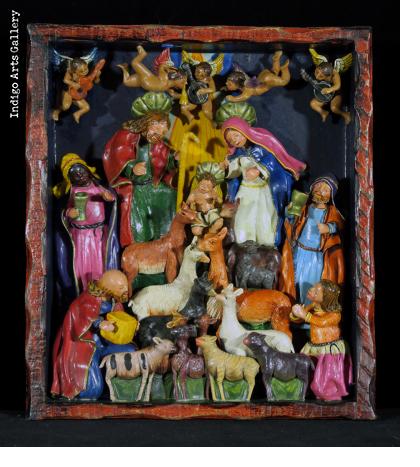

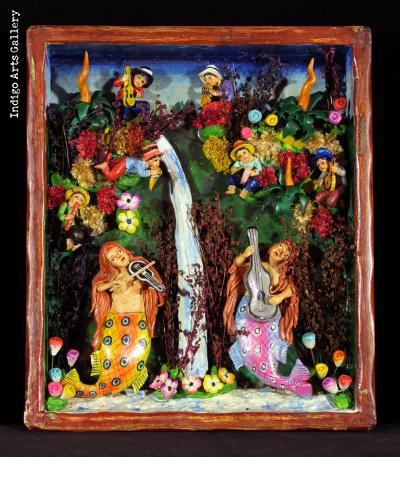

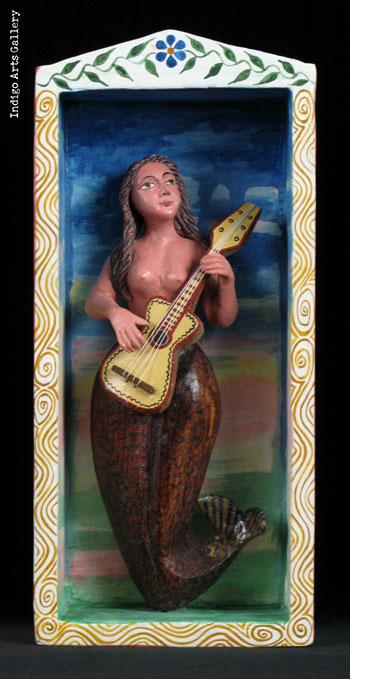

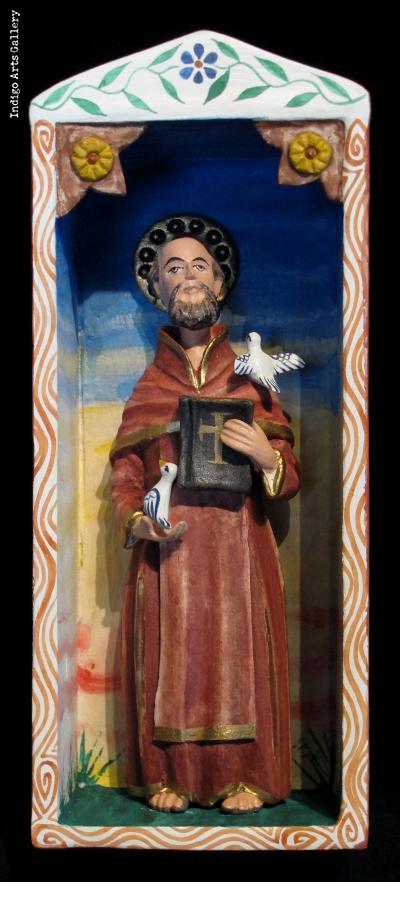

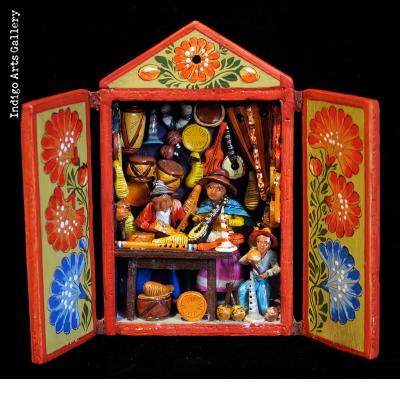

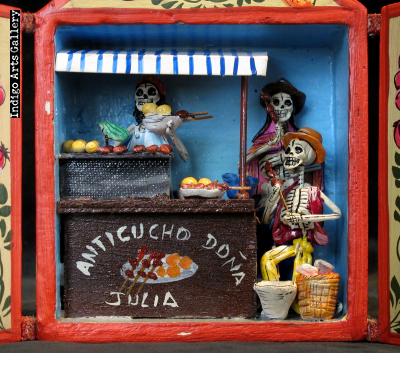

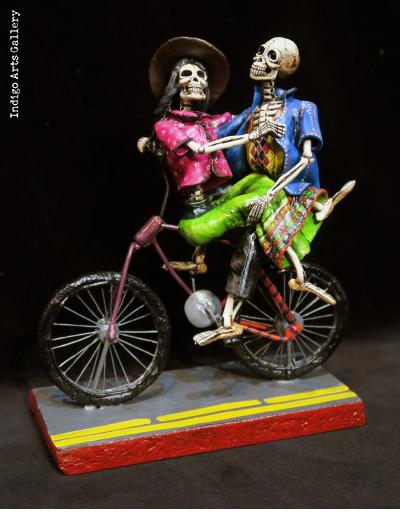

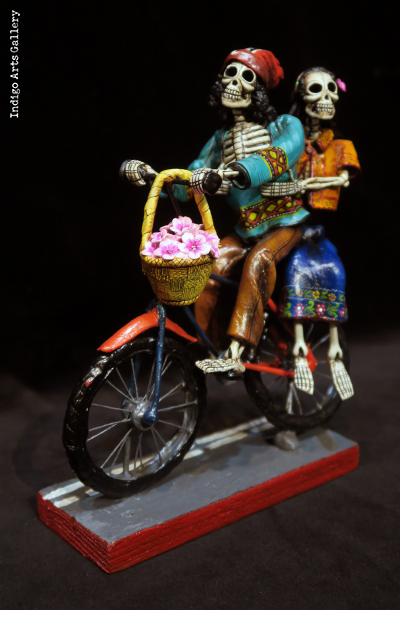

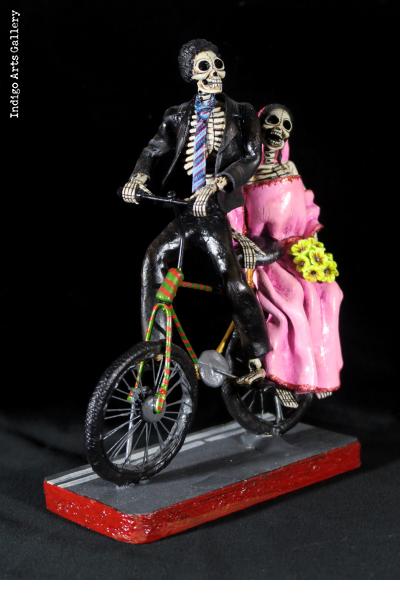

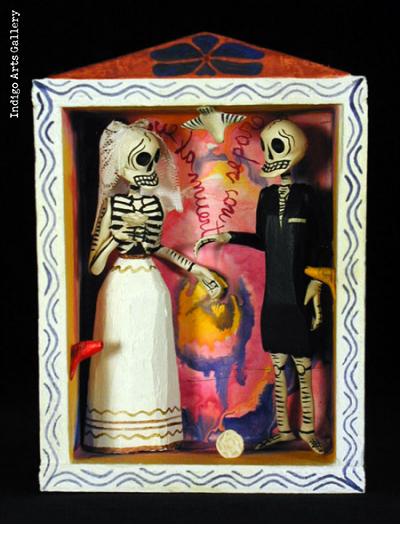

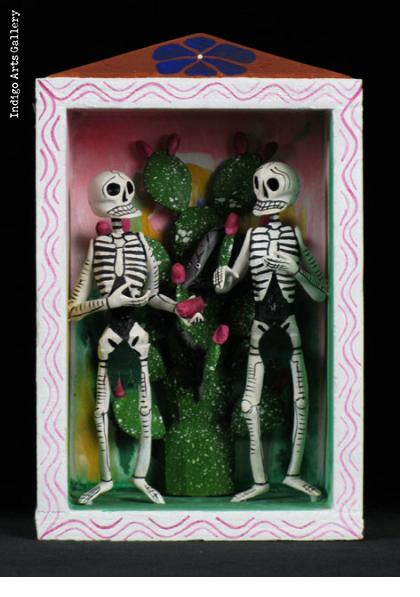

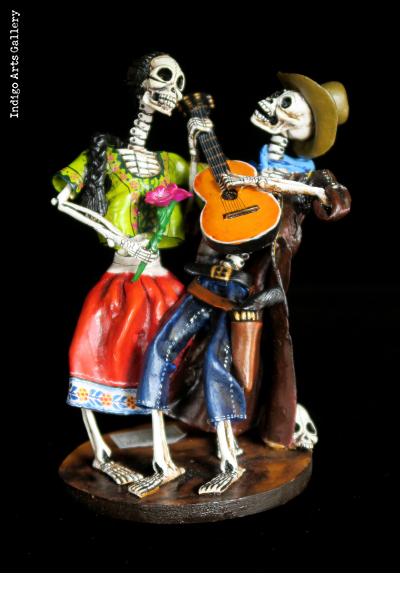

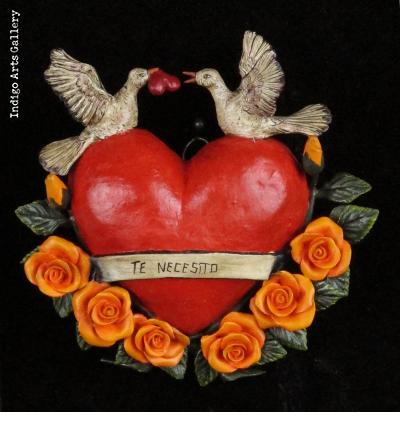

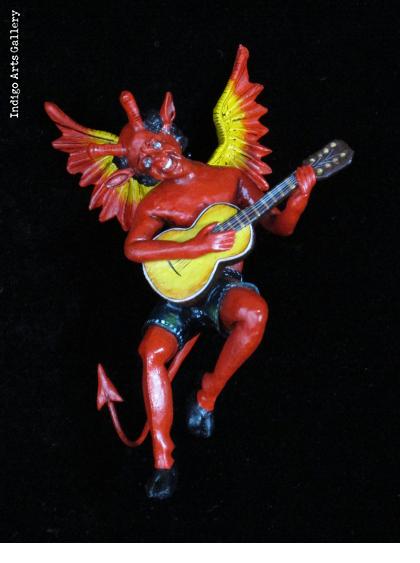

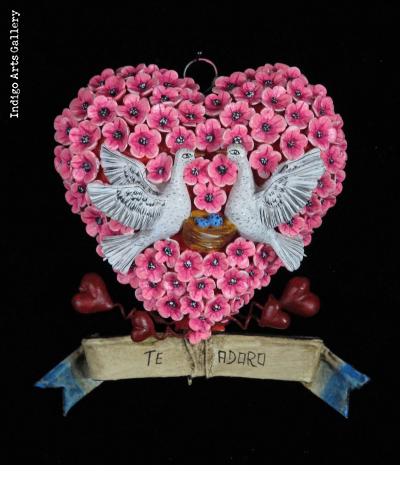

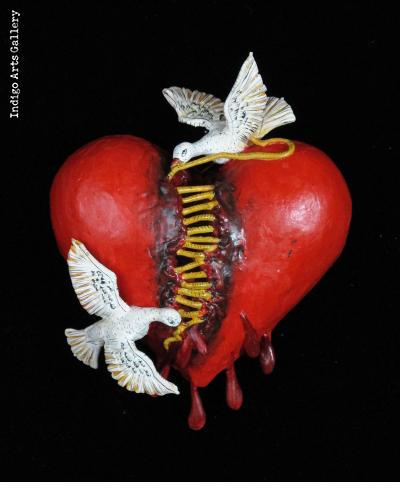

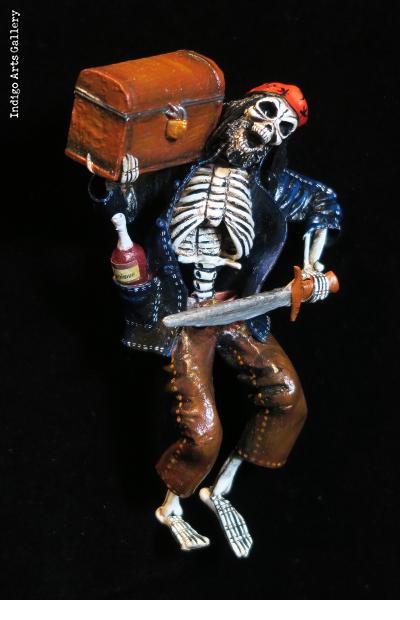

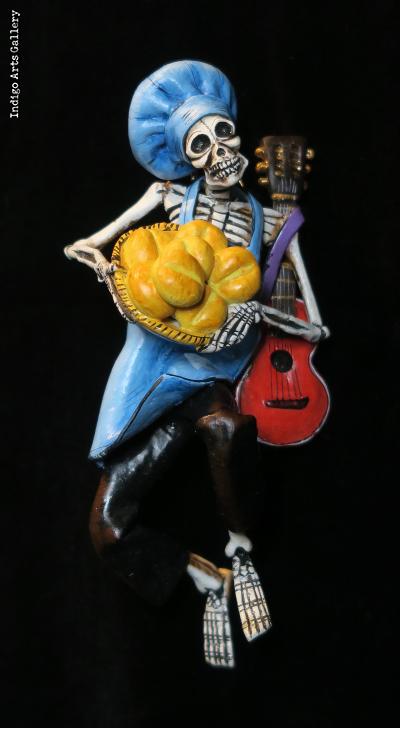

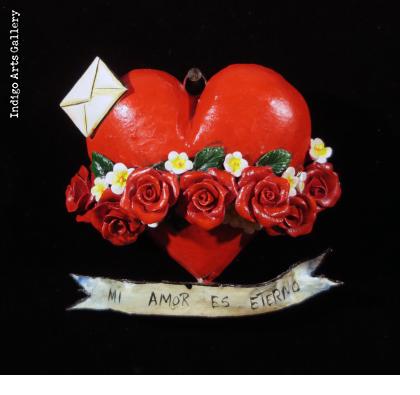

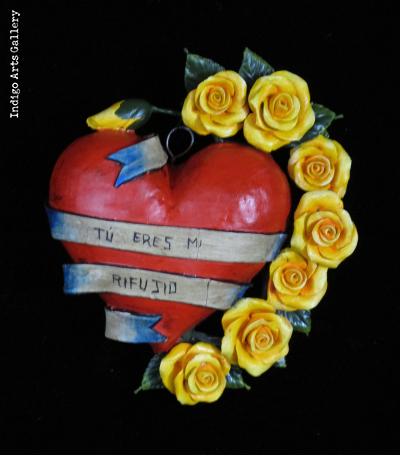

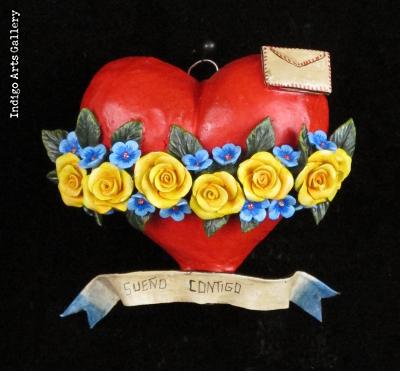

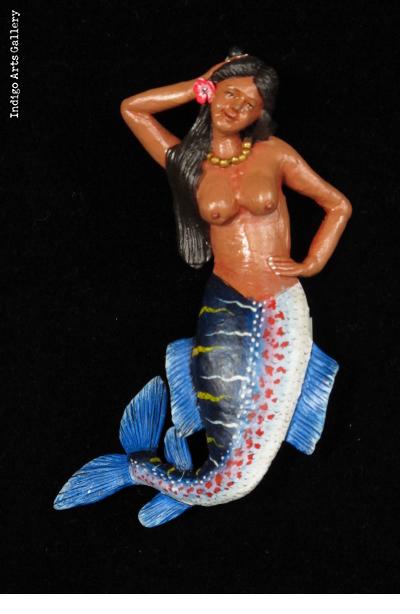

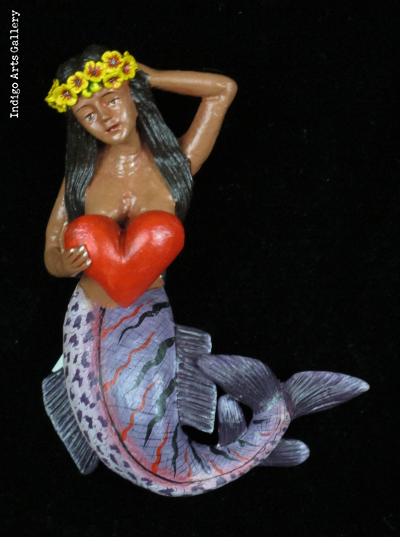

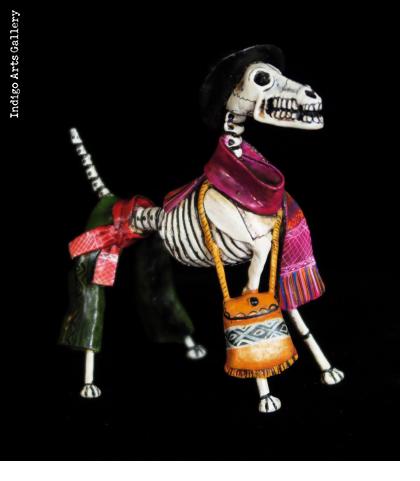

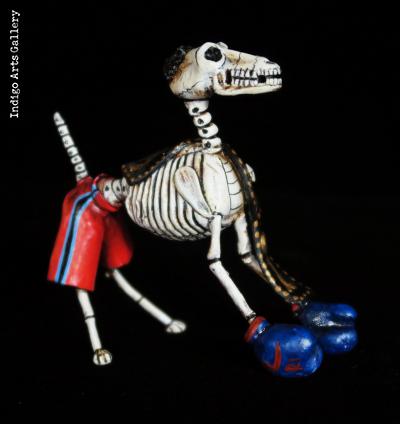

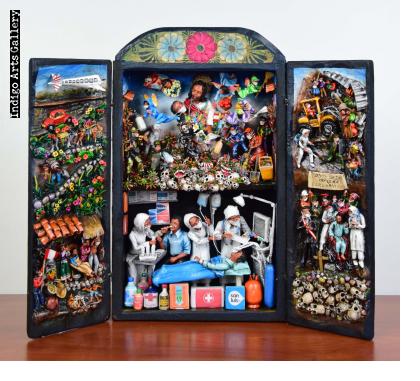

The traditional Peruvian retablo is a portable shrine or nicho that holds figures sculpted of pasta (a mixture of plaster and potato) or maguey cactus wood. The making of retablos is a folk art whose roots go back to the sixteenth century in the Andes (and even to the Greeks and Romans before that). While the art’s origins are religious, the contemporary Peruvian retablos exhibited at Indigo Arts range from the sacred to the profane. Claudio Jimenez Quispé is the acknowledged master of the Peruvian retablo. He and his family are heirs to a multi-generation artistic tradition in the highland region of Ayacucho. Most of the family moved to Lima during the brutal civil war of the 1980’s and early 1990’s, which pitted a violent revolutionary group, the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) against equally ruthless government forces. The peasants caught in the middle suffered the deaths or disappearances of some 70,000 people in this period. The effect on the retablo art form was profound. New narratives of social strife and civil war entered the artists’ repertoire. Many contemporary retablos reflect an exposure to the urban world of Lima and beyond, not to mention a response to a world-wide market for folk art. Some of the recent work shows strong influences of Mexican folk art, including scenes of death and the underworld that celebrate the Dias de los Muertos (Days of the Dead) holidays.

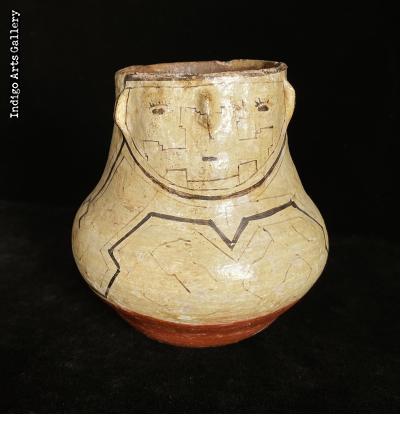

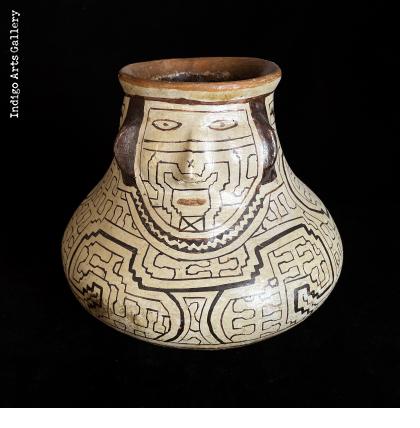

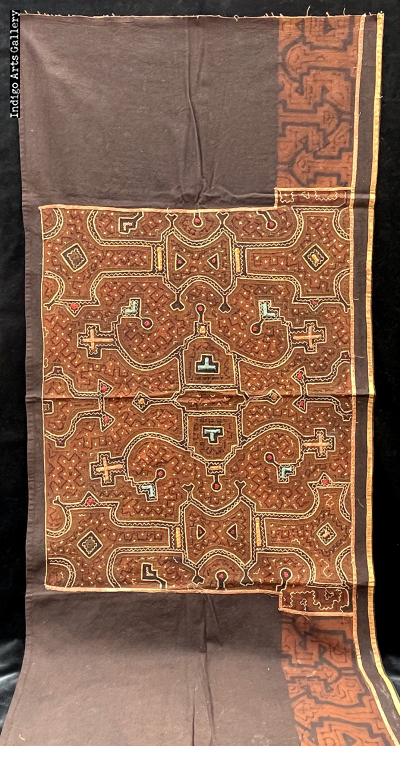

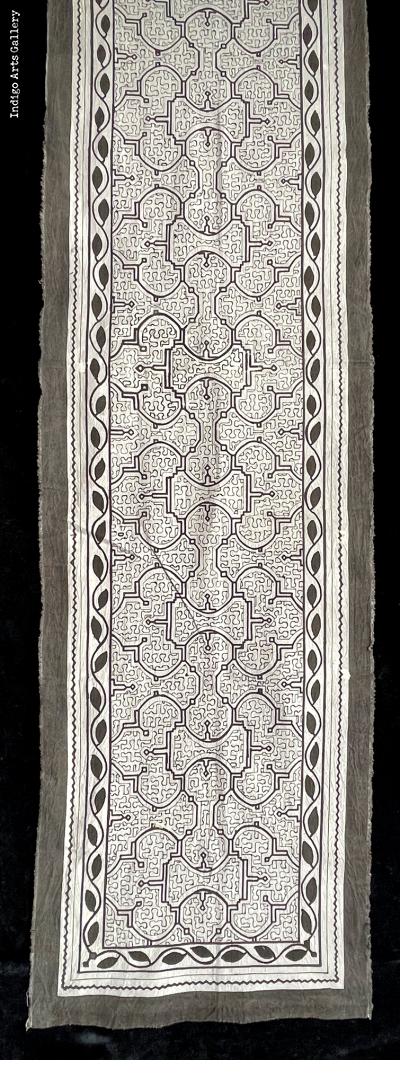

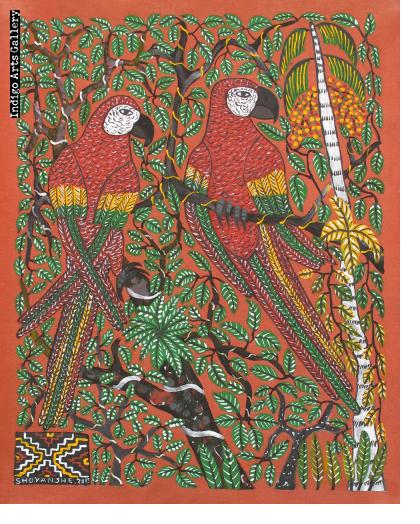

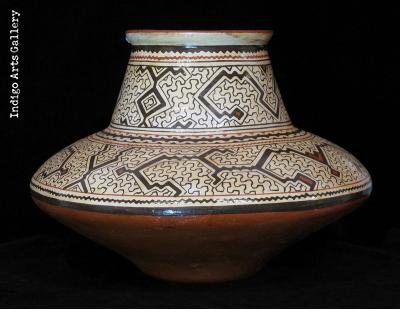

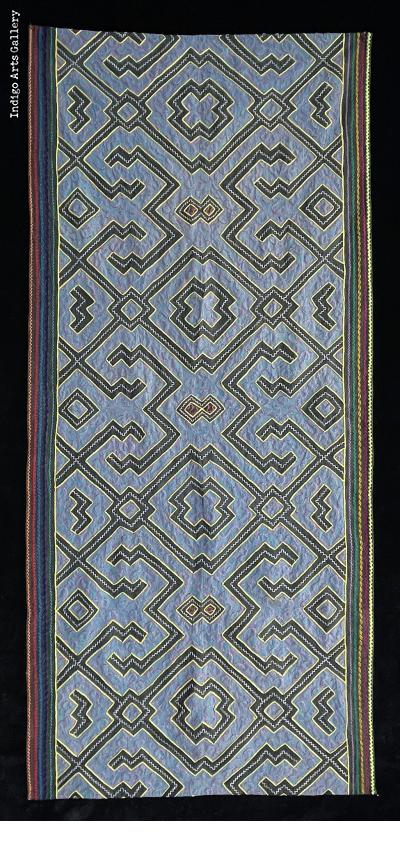

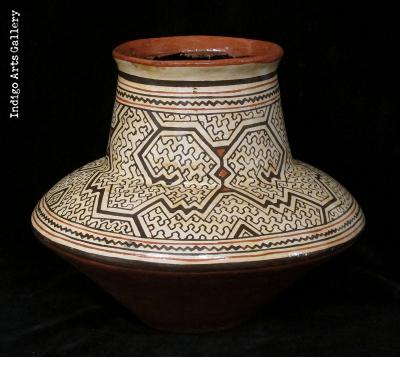

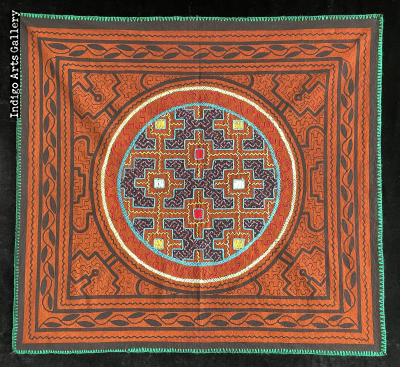

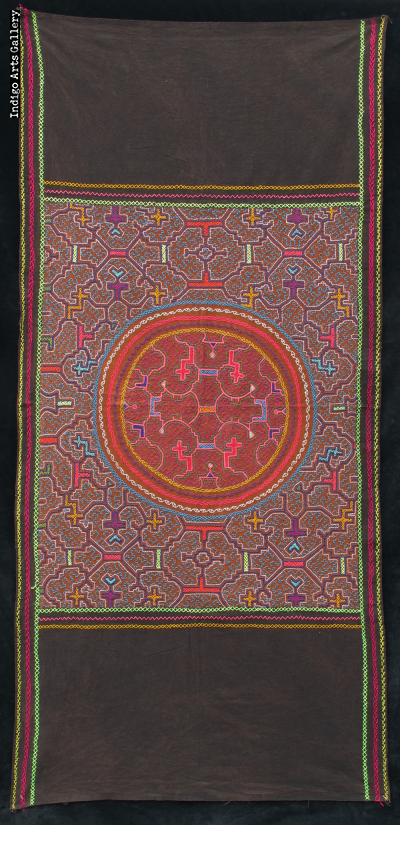

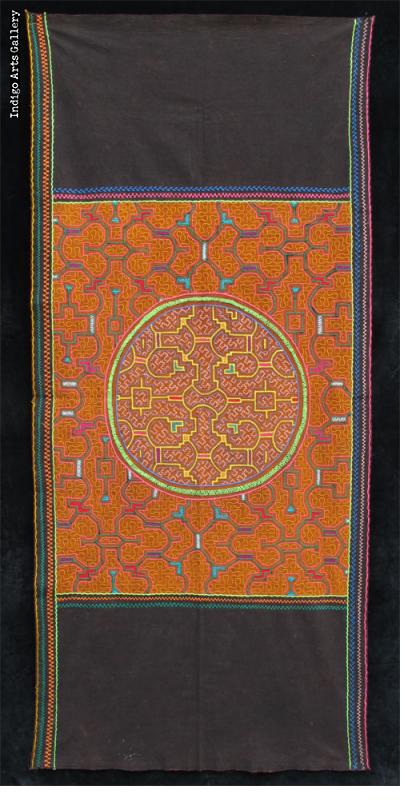

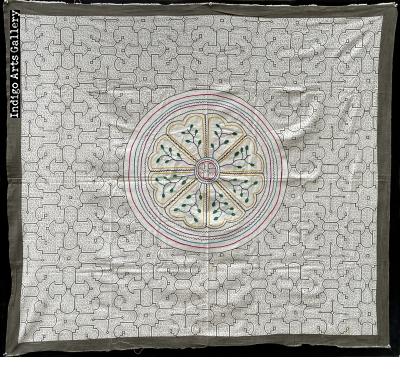

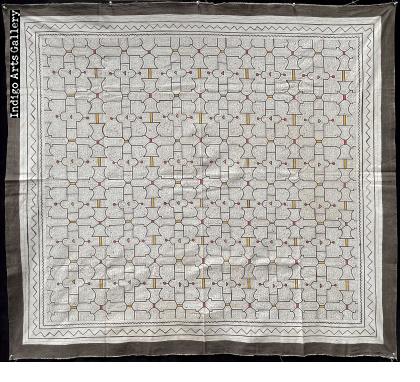

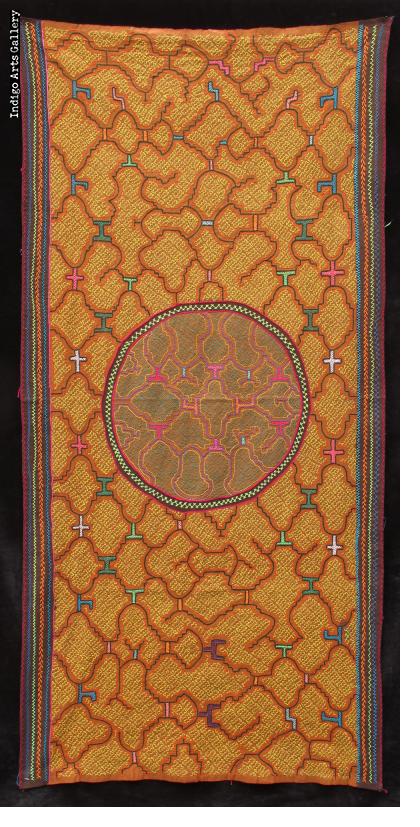

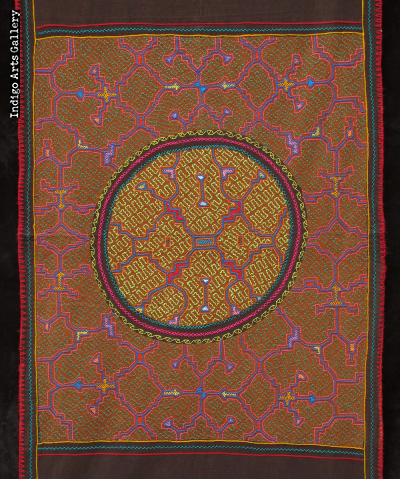

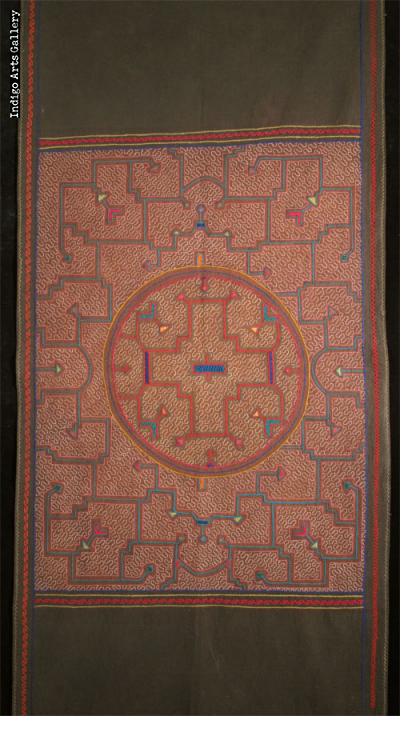

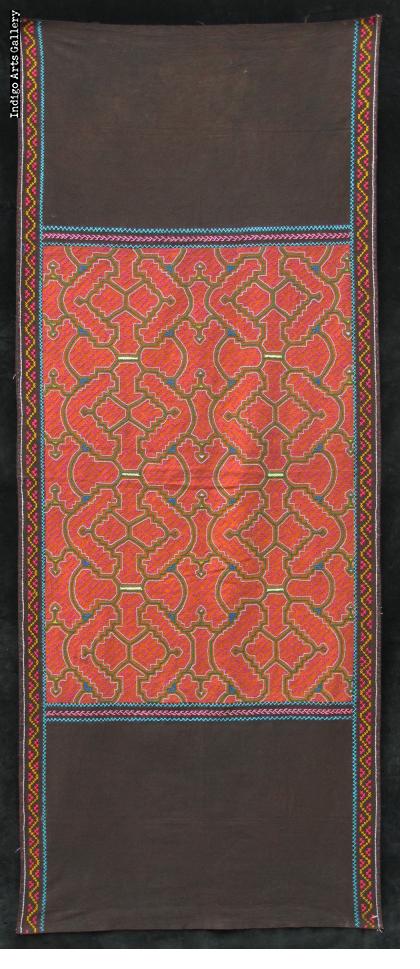

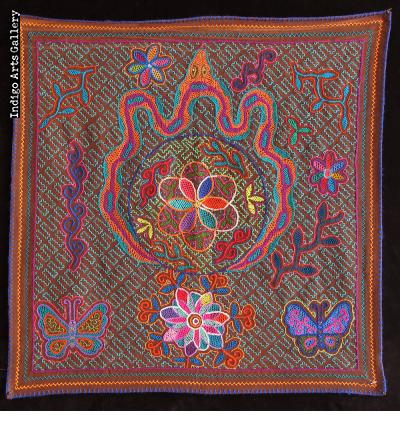

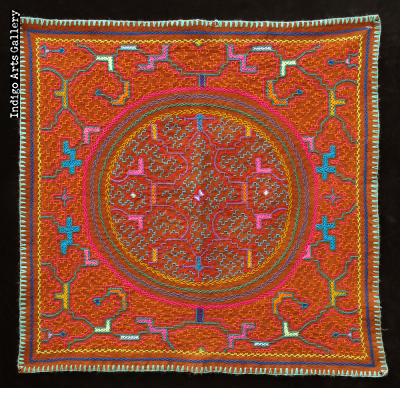

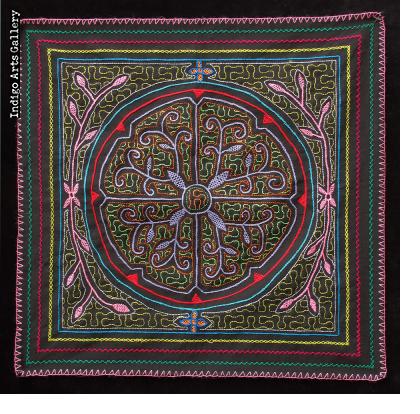

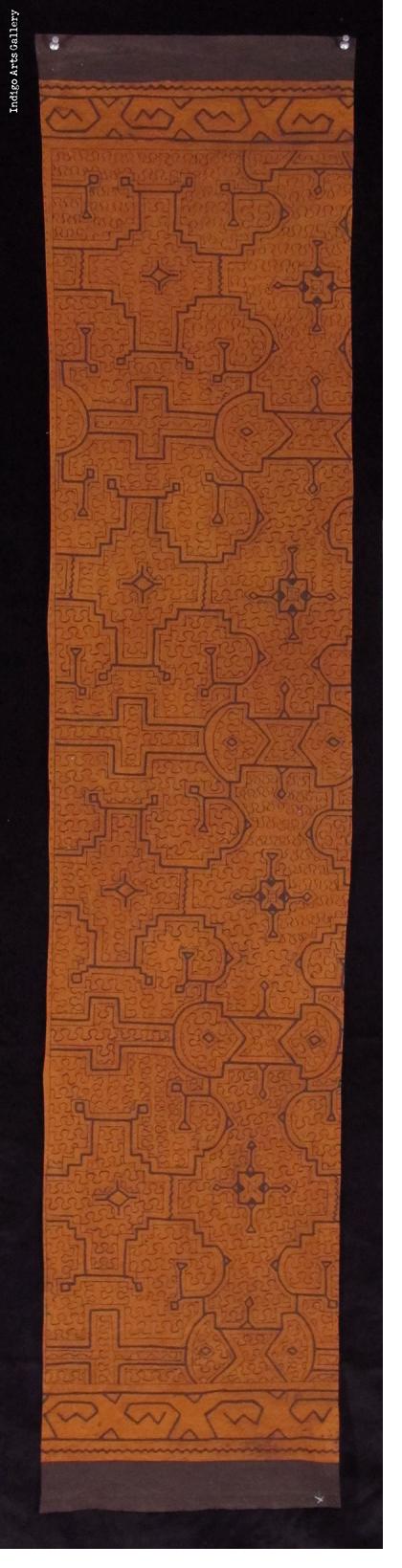

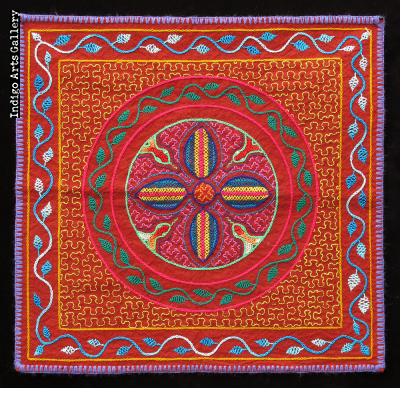

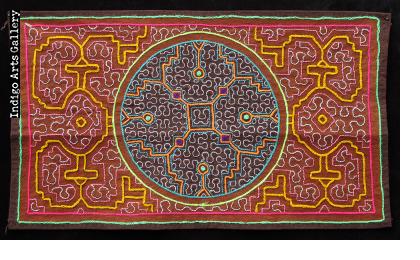

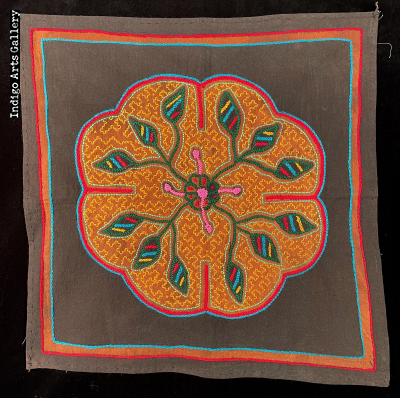

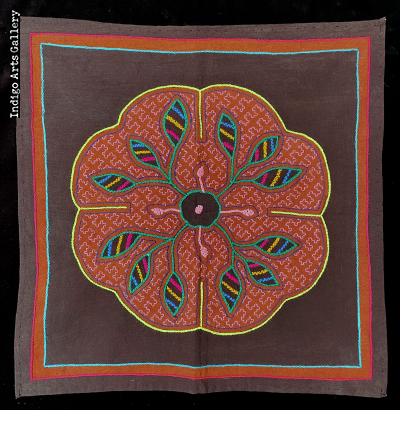

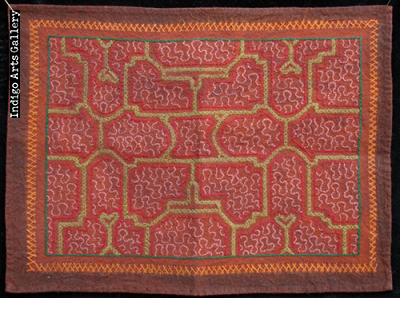

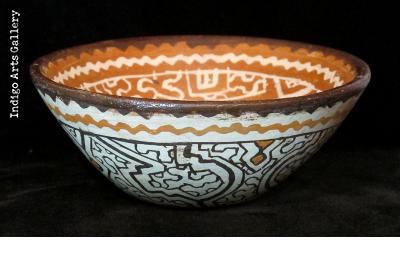

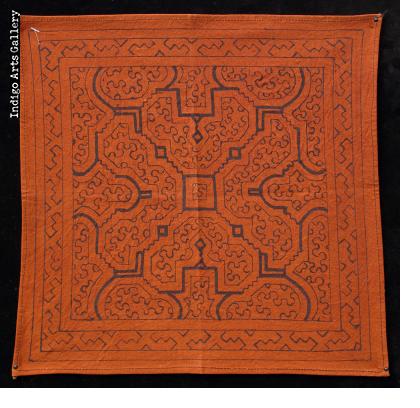

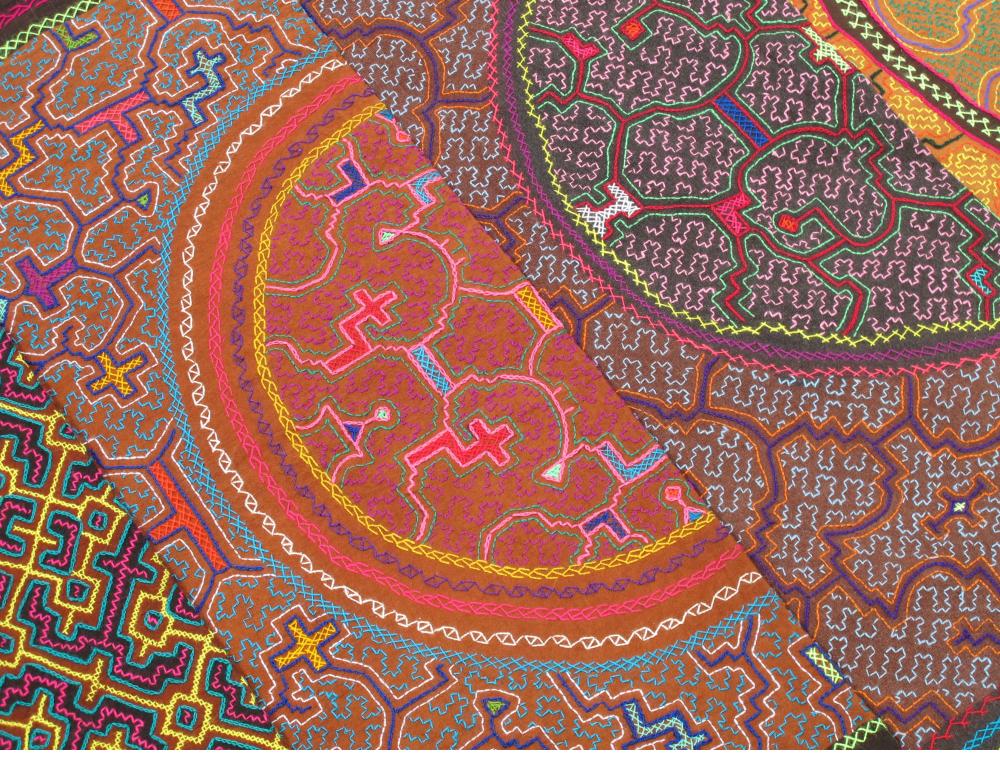

The Shipibo-Conibo are an indigenous people (currently numbering only about 20,000) who live along the Ucayali river in the Amazon basin east of the Andes. Though an increasing portion of the Shipibo population have been urbanized in settlements such as Pucallpa, their traditions remain strong, as expressed in their shamanistic religion and in their visionary arts – notably in the patterns that the Shipibo women paint on their pottery, clothing, textiles and their bodies. The ethnologist Angelika Gebhart-Sayer terms their art “visual music”.

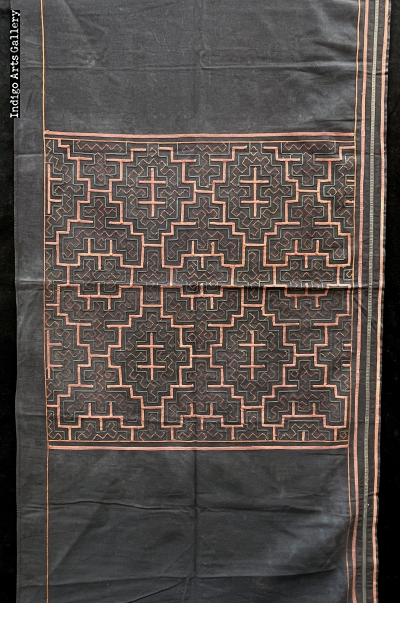

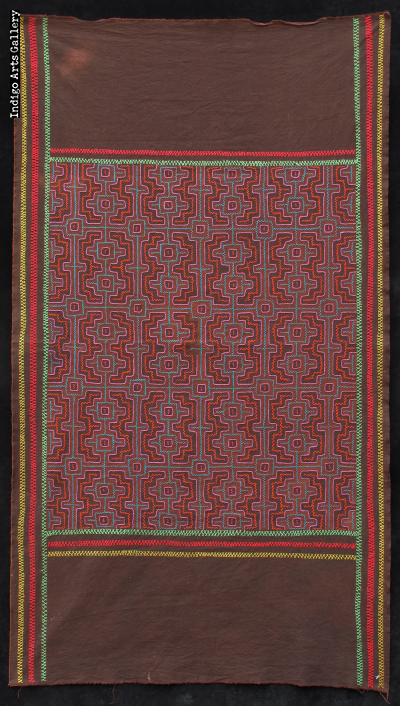

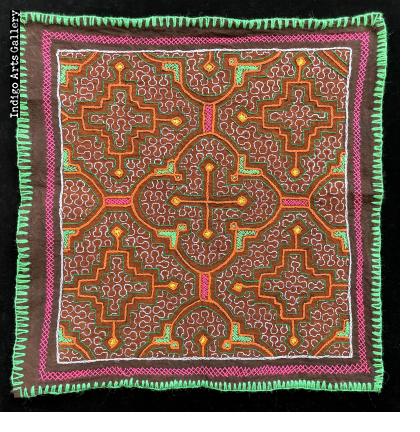

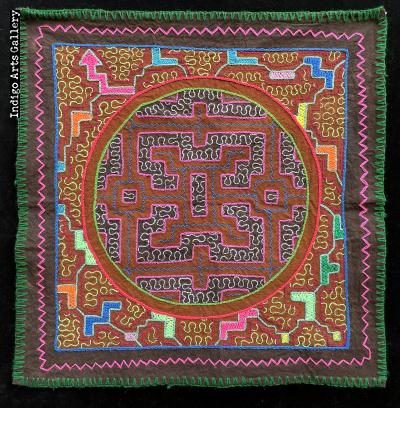

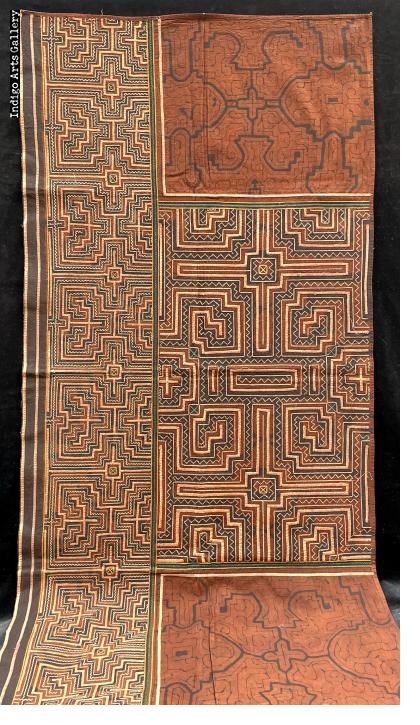

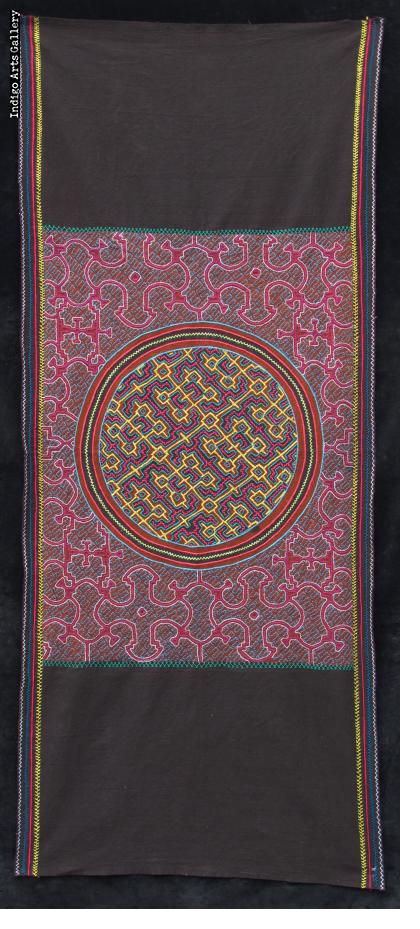

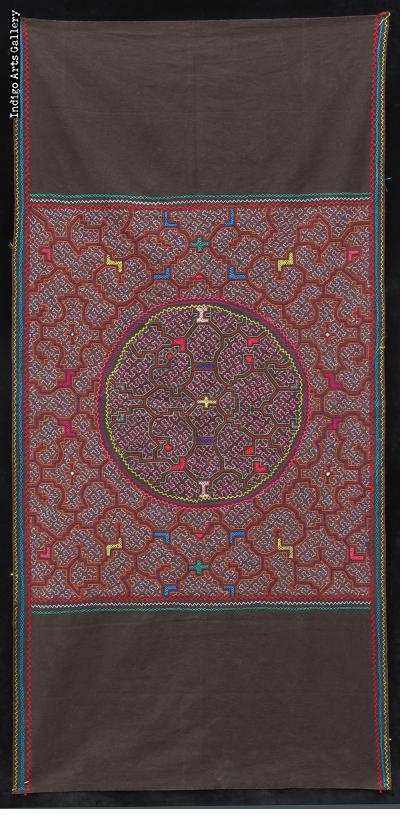

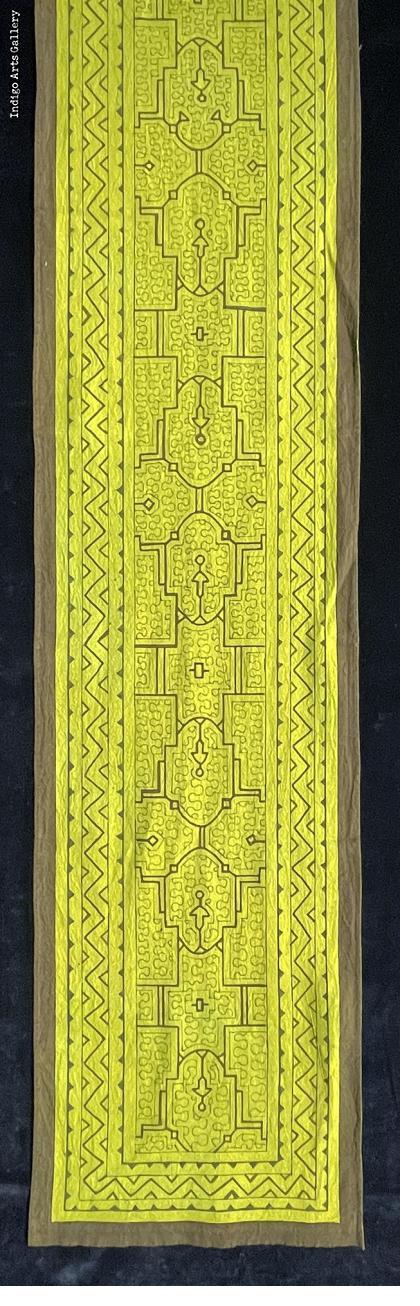

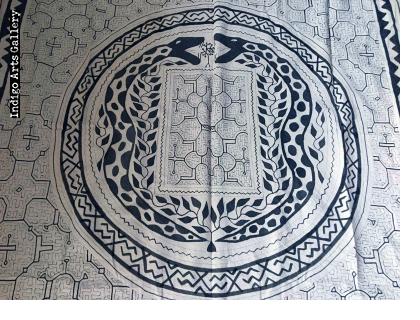

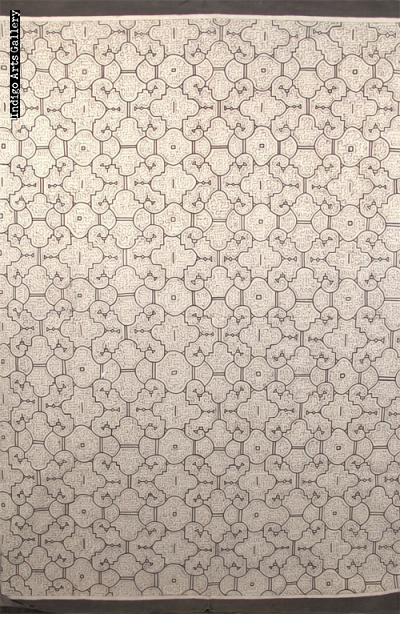

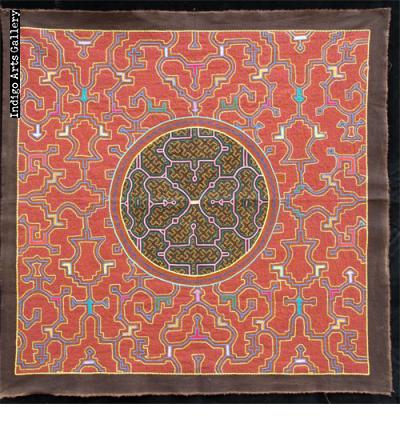

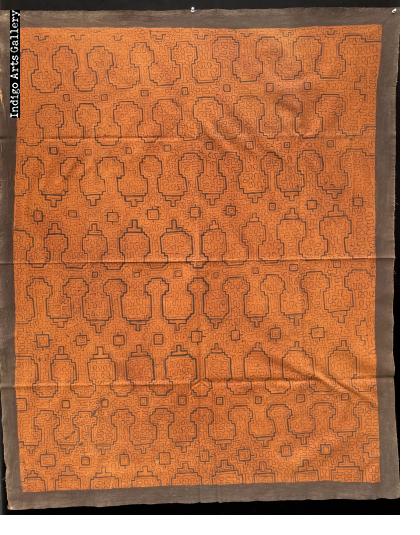

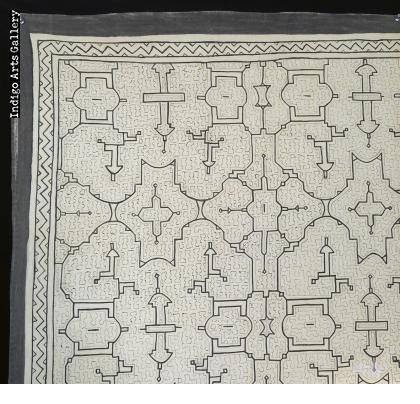

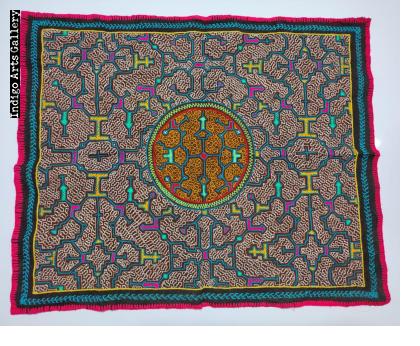

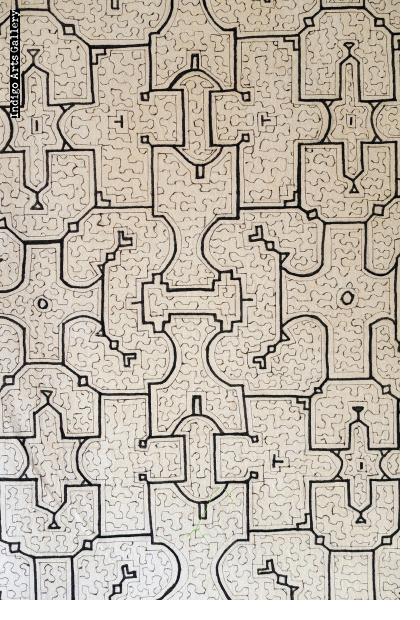

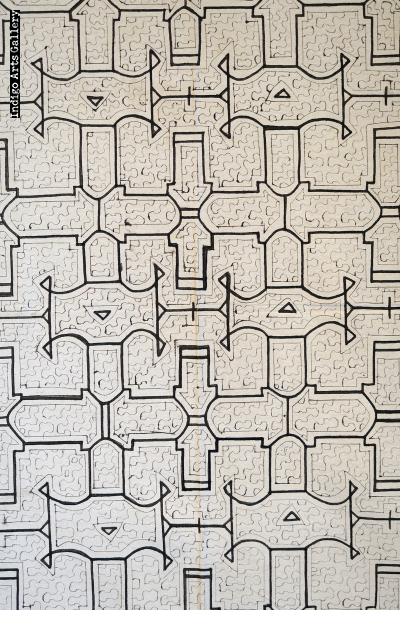

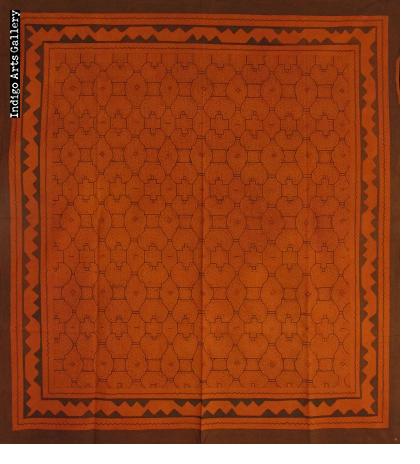

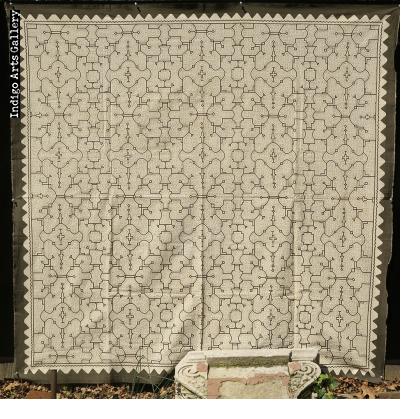

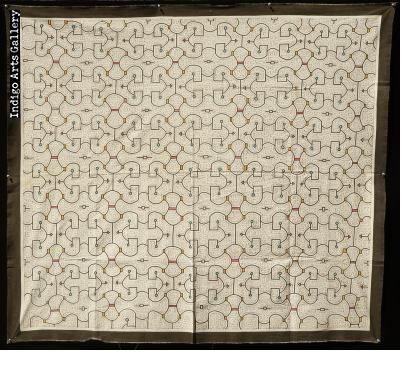

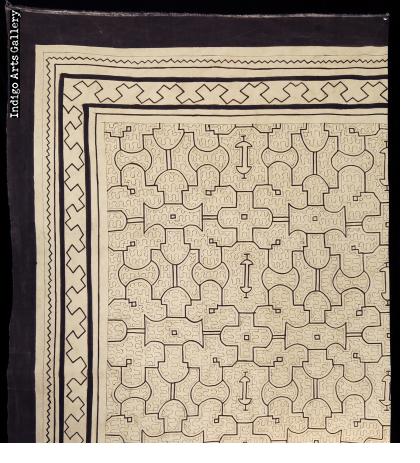

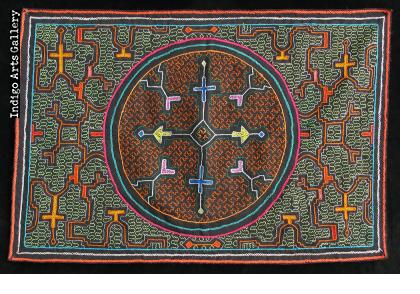

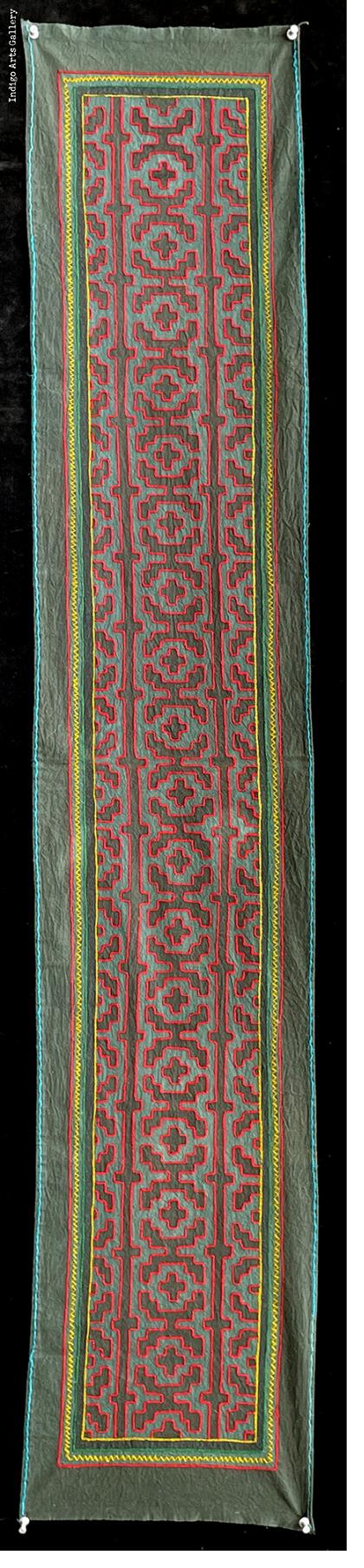

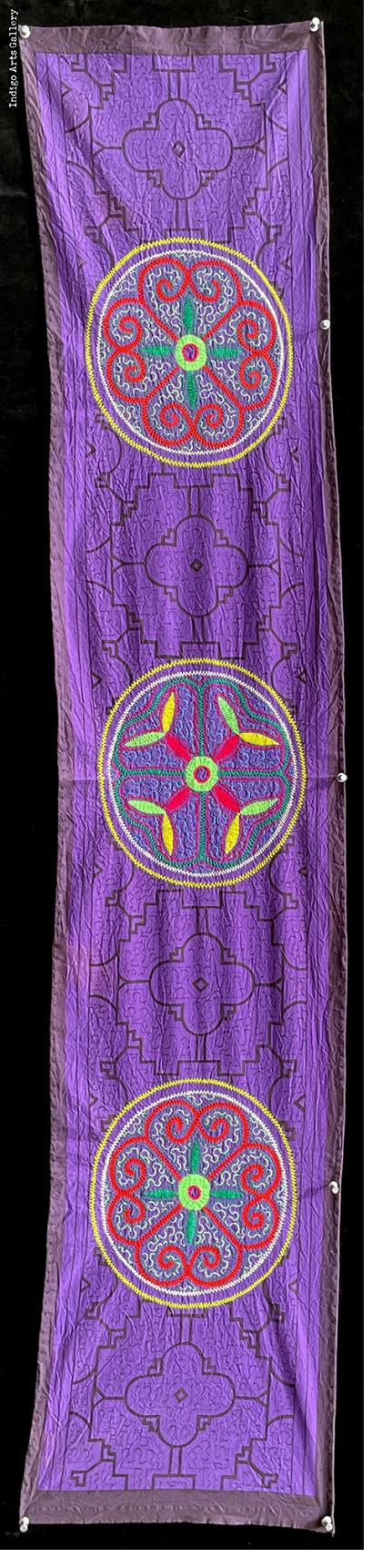

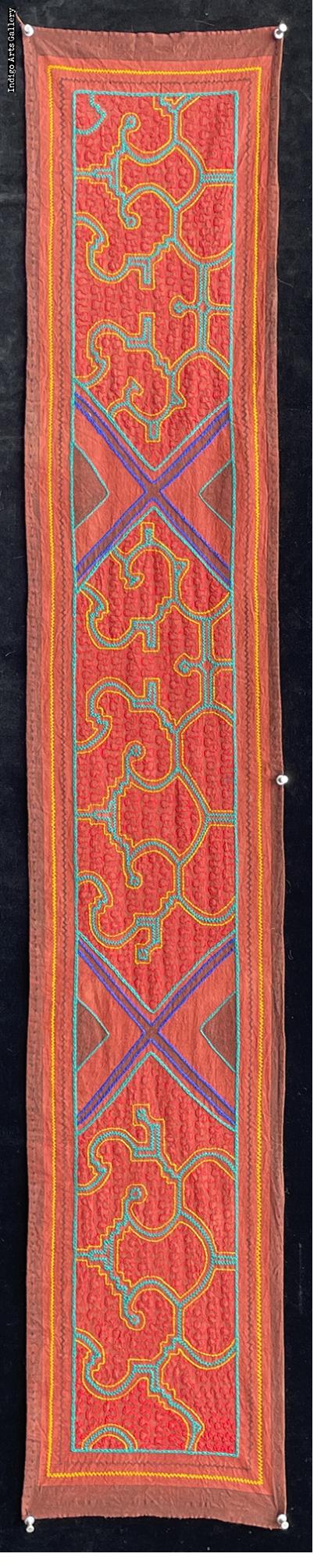

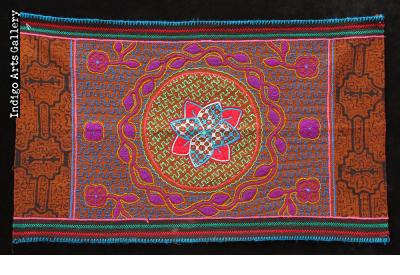

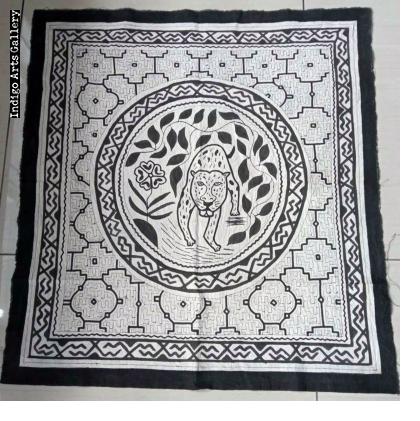

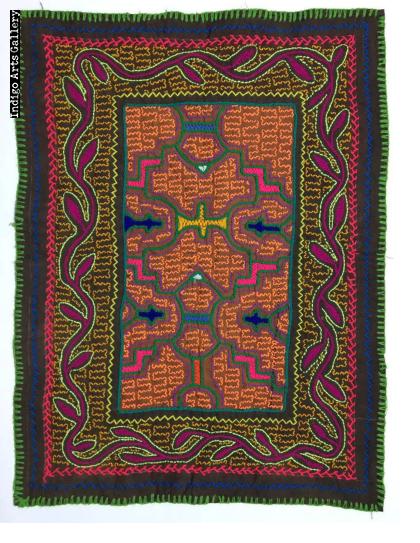

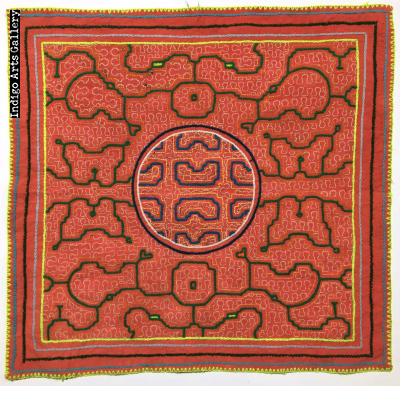

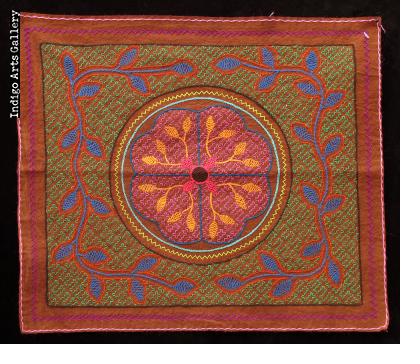

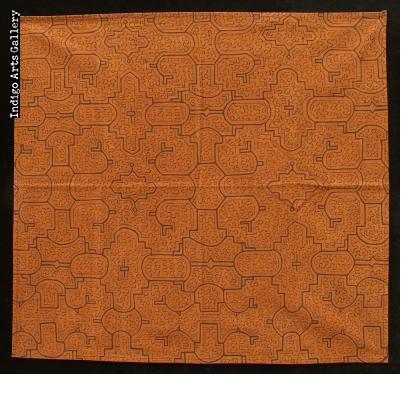

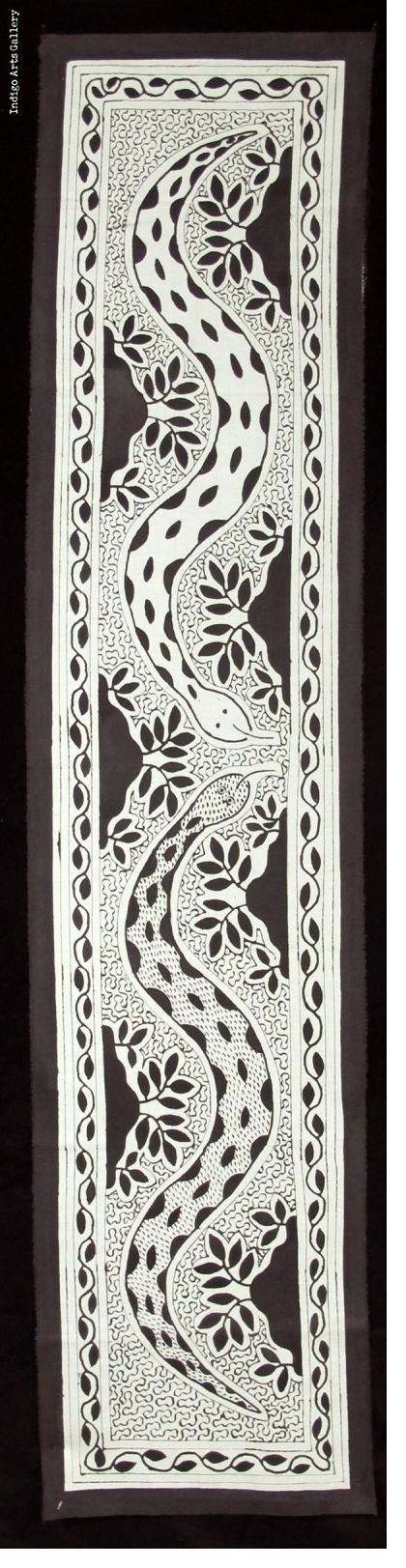

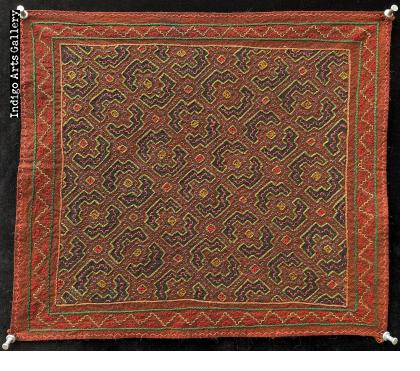

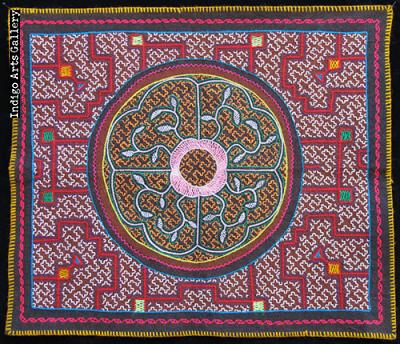

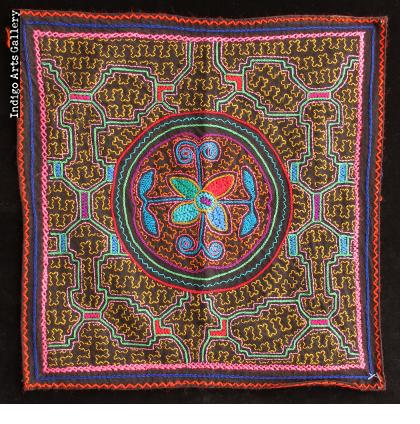

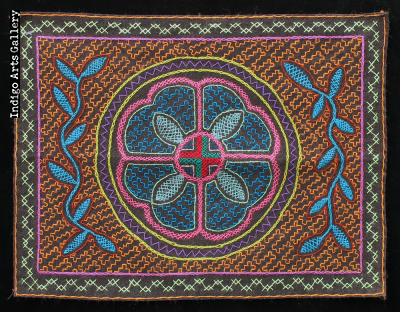

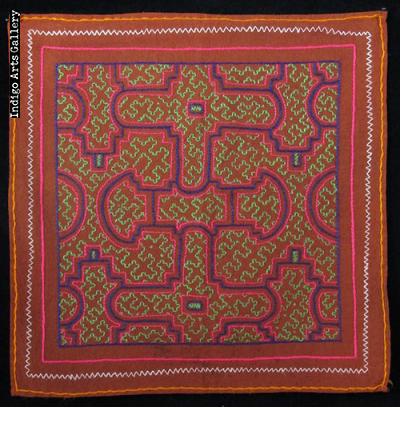

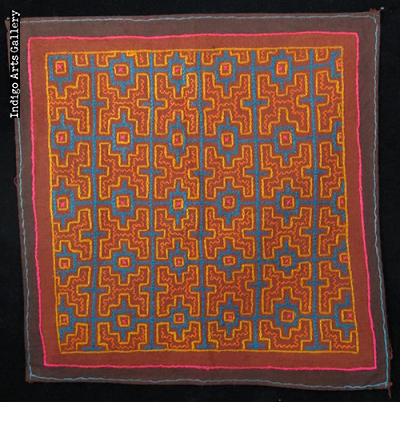

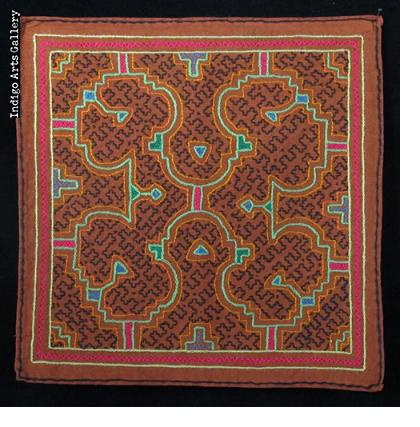

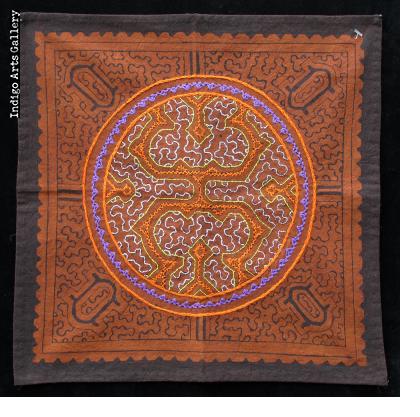

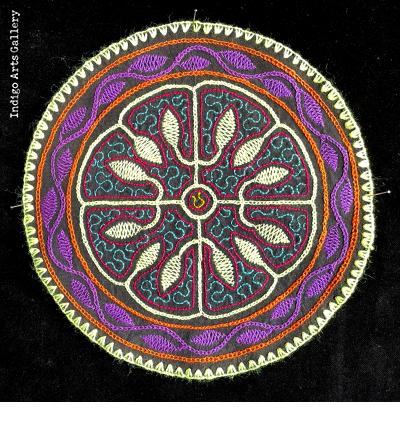

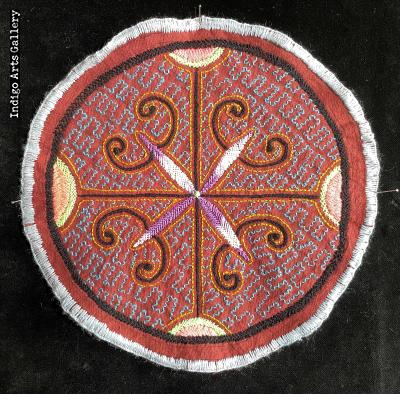

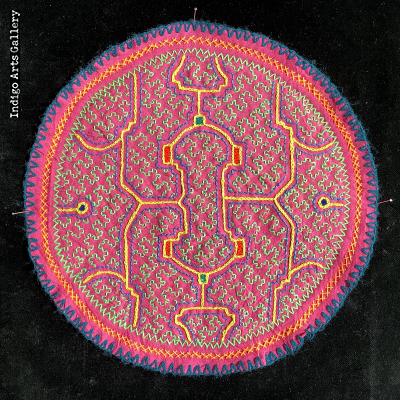

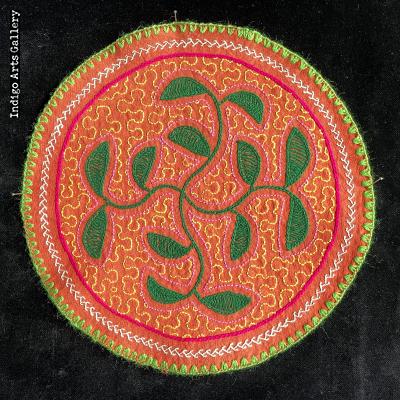

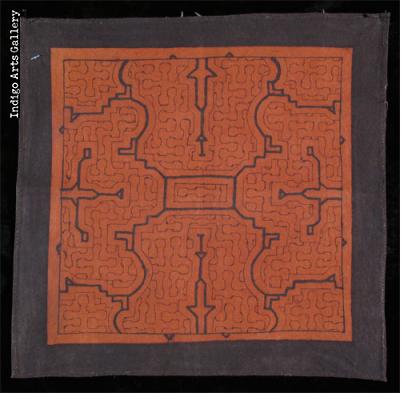

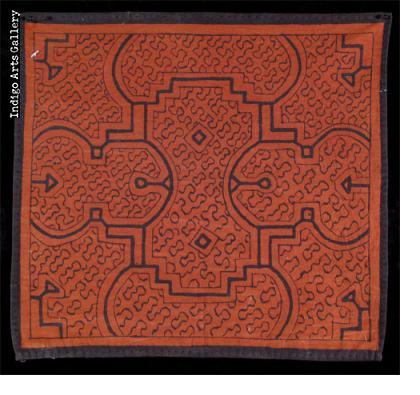

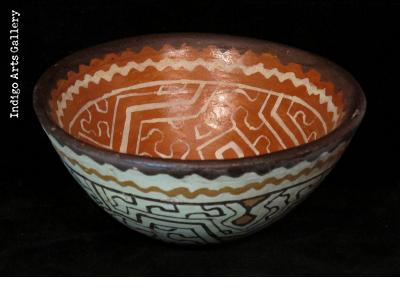

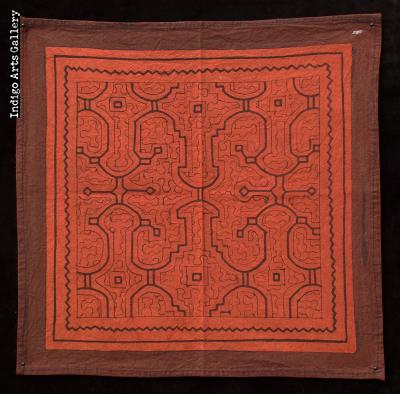

The Shipibo are known for labyrinthine geometric designs that reflect their culture and their cosmology. The main elements of the designs are the square, the rhombus, the octagon and the cross, which “represents the southern Cross constellation which dominates the night sky and divides the cosmos into four quadrants…”* Other symbols featured in the designs are the Cosmic Serpent, the Anaconda and various plant forms, notably the caapi vine used in the preparation of the sacramental drug Ayahuasca. There is an intriguing tie between the visual and aural in Shipibo art: “ the Shipibo can listen to a song or chant by looking at the designs, and inversely paint a pattern by listening to a song…”*

The designs are traditionally drawn with natural huito berry pigments on hand-woven cotton fabrics that are worn as wrap-around skirts. The fabric is either natural or dyed with a red-brown dye made from mahogany bark. Today most of the fabric is machine-woven, purchased from traders, and increasingly the hand-drawn designs are supplemented with patterns embroidered with bright-colored commercial yarns. The results can be stunning. The truly psychedelic color combinations are consistent with ayahuasca visions. More often than not the designs are asymmetrical within a border or frame – like a landscape viewed through an airplane window: “Although in our cultural paradigm we perceive that the geometric patterns are bound within the border of the textile or ceramic vessel, to the Shipibo the patterns extend far beyond these borders and permeate the entire world.”*

* Howard G. Charing