Works by the Finest Sequin Artists in Haiti

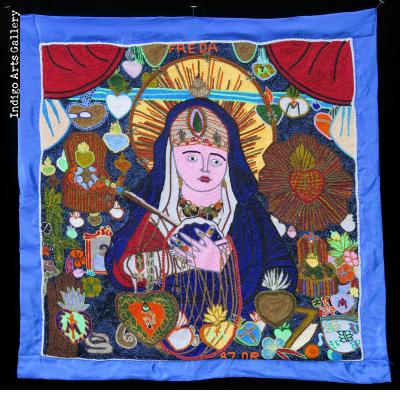

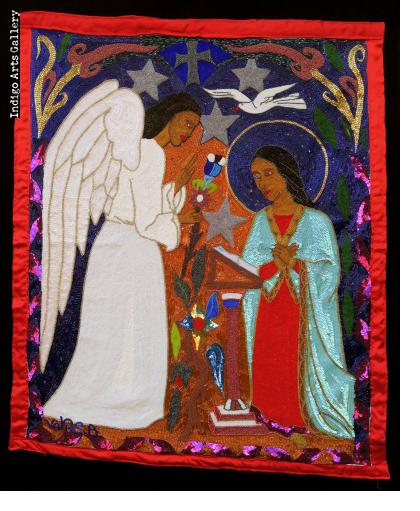

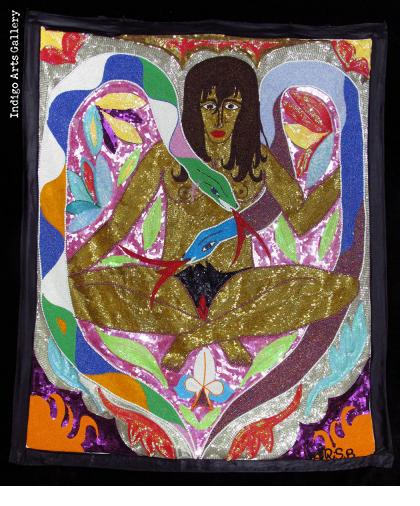

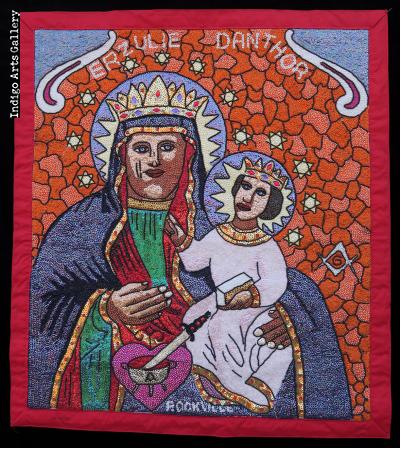

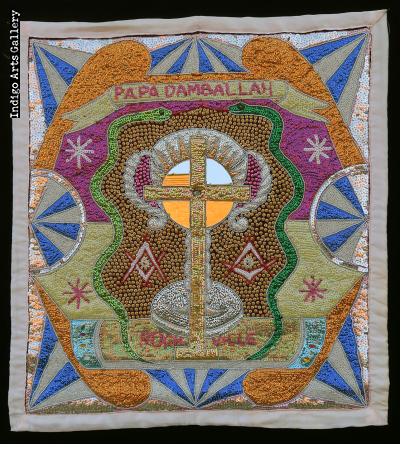

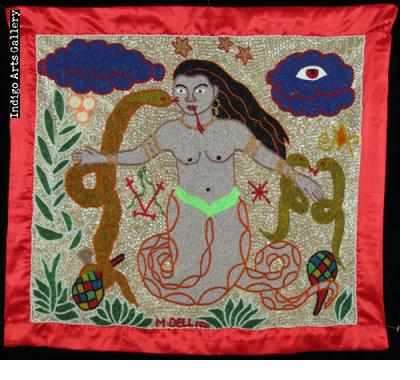

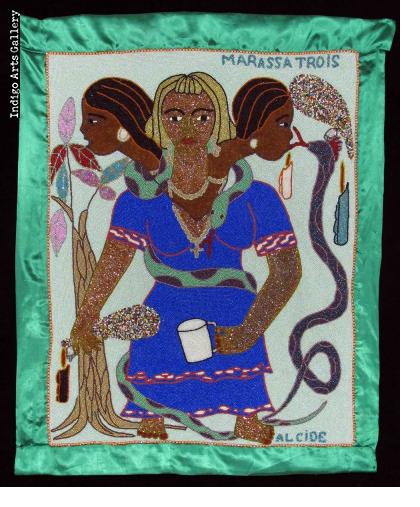

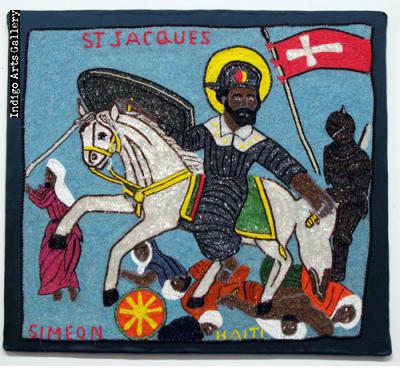

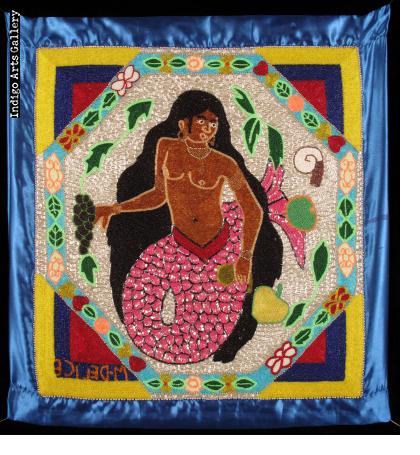

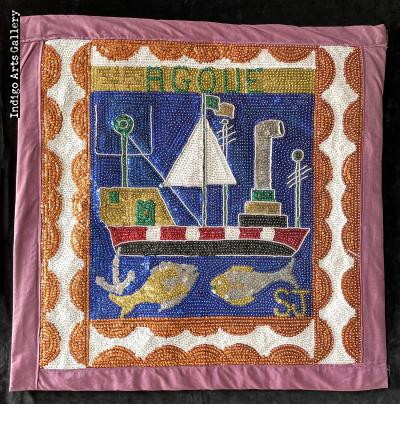

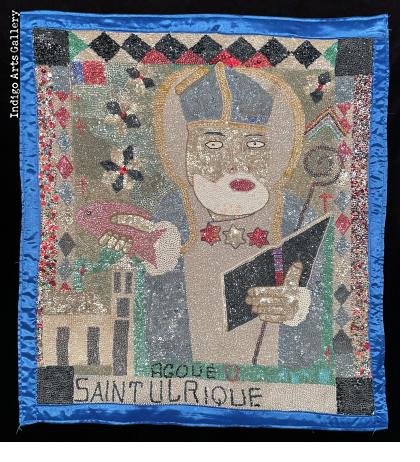

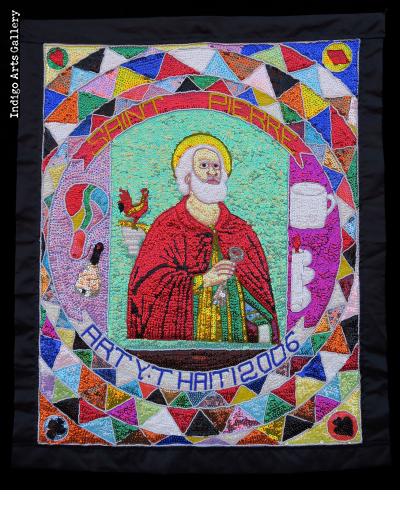

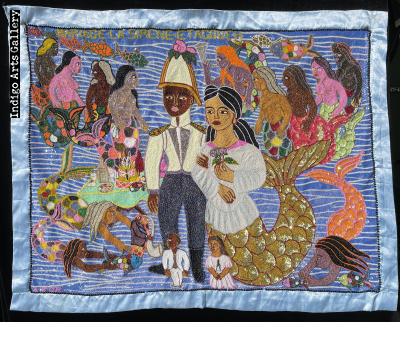

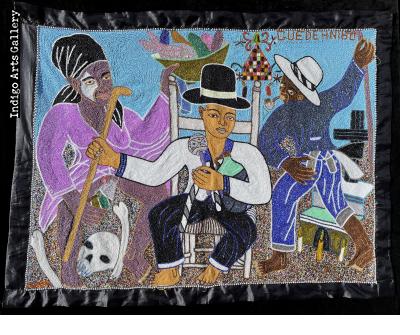

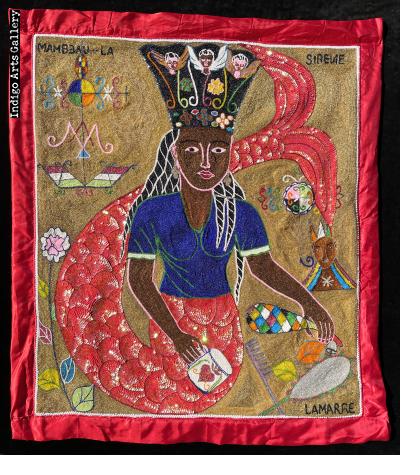

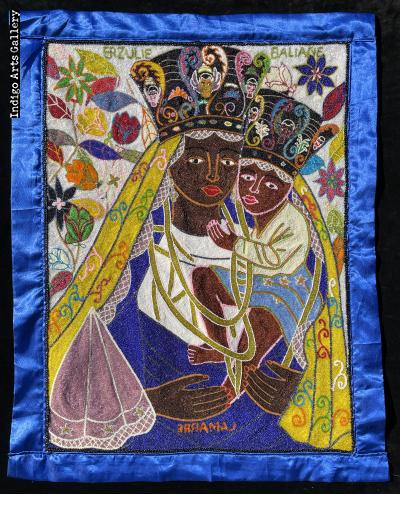

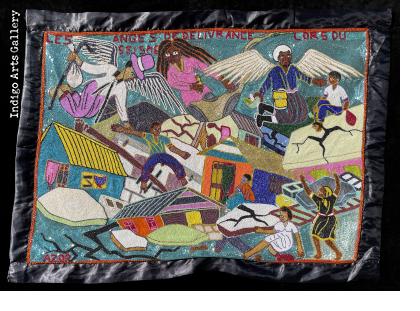

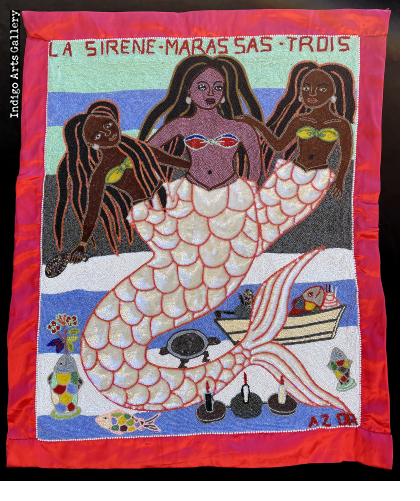

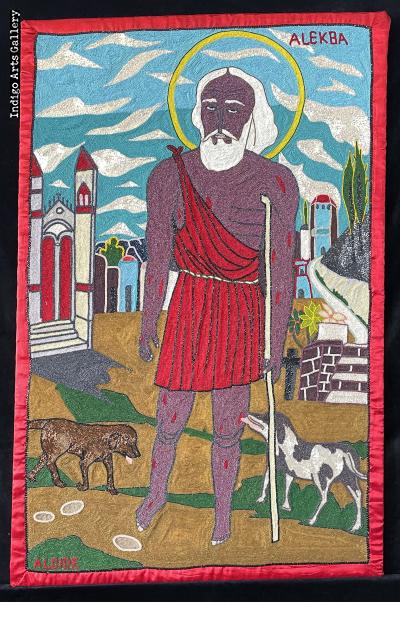

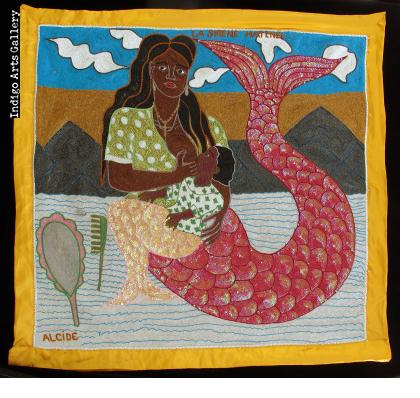

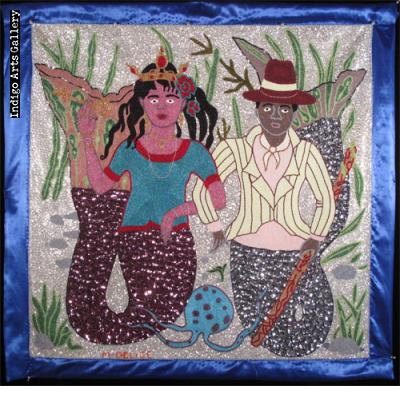

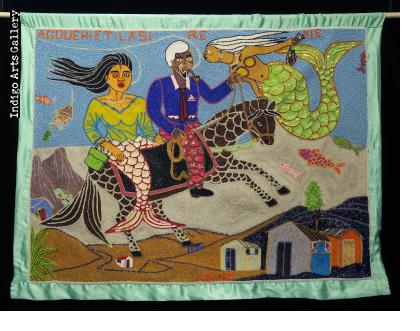

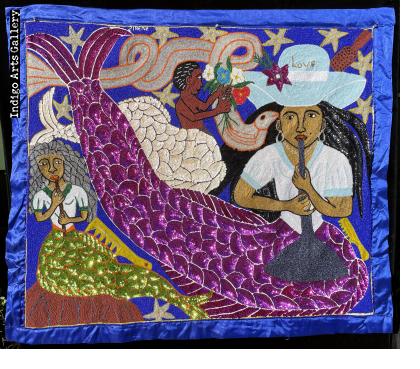

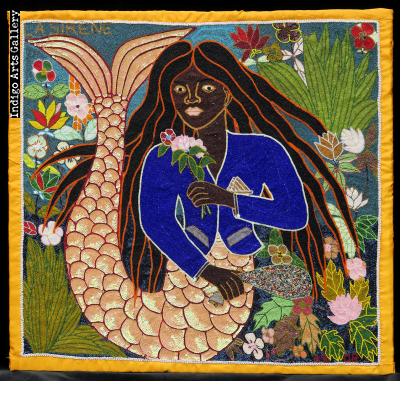

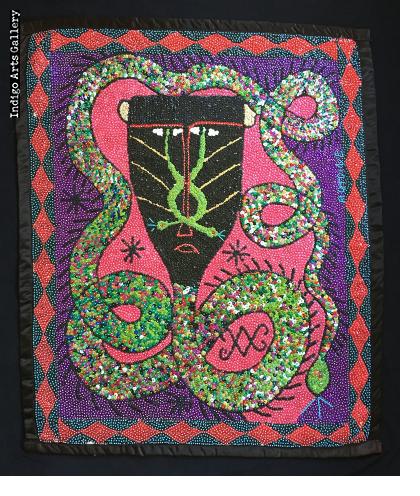

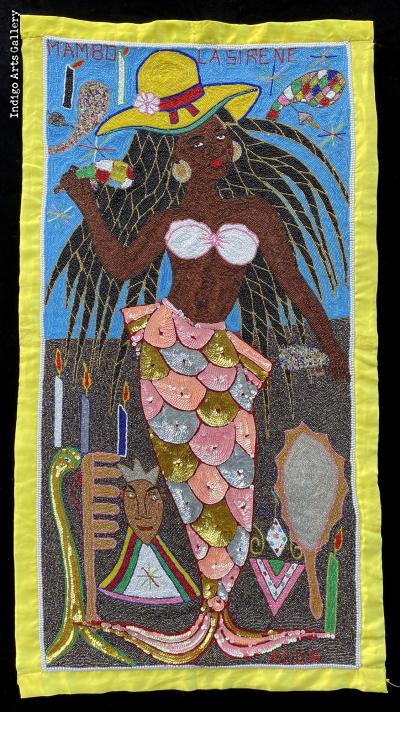

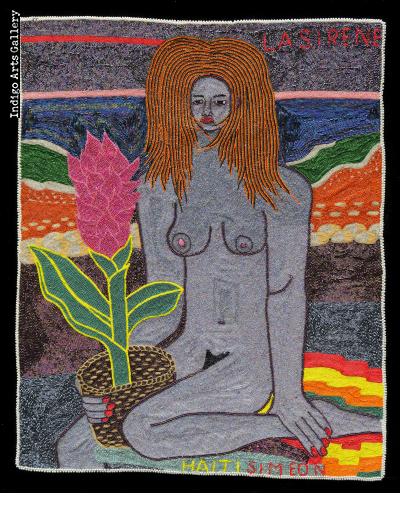

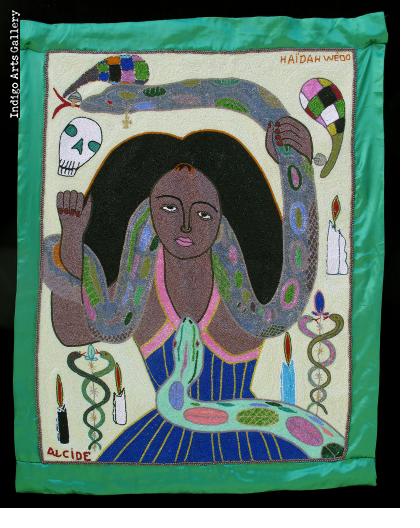

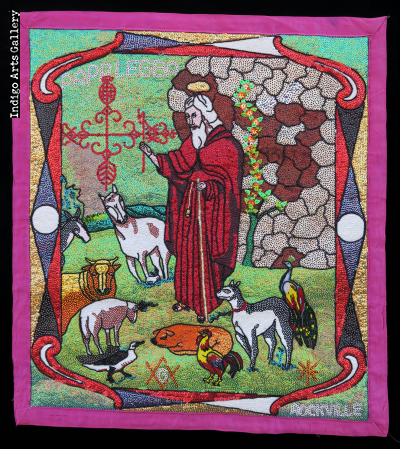

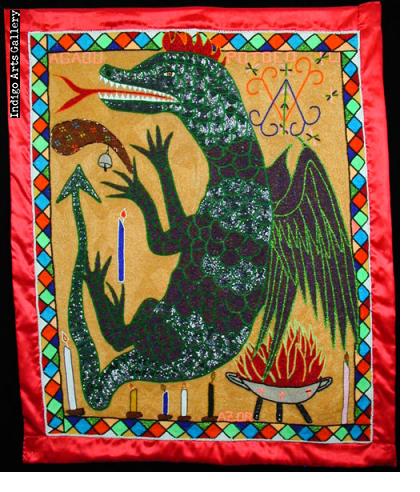

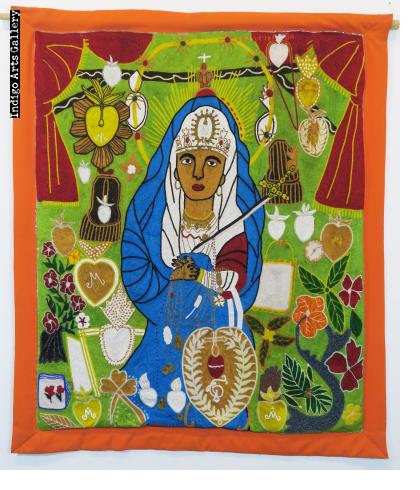

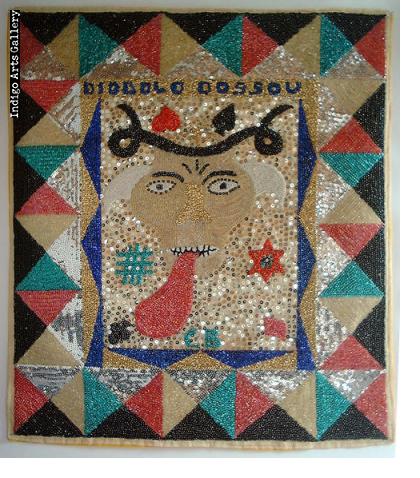

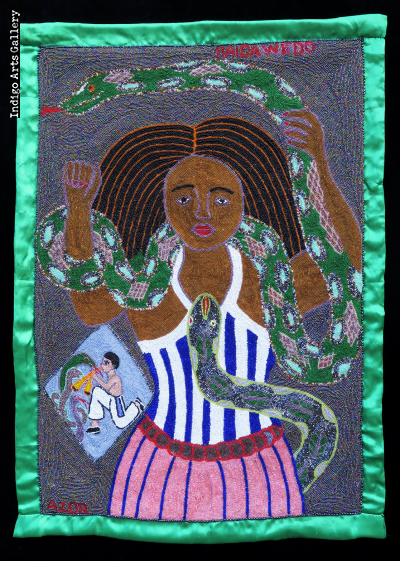

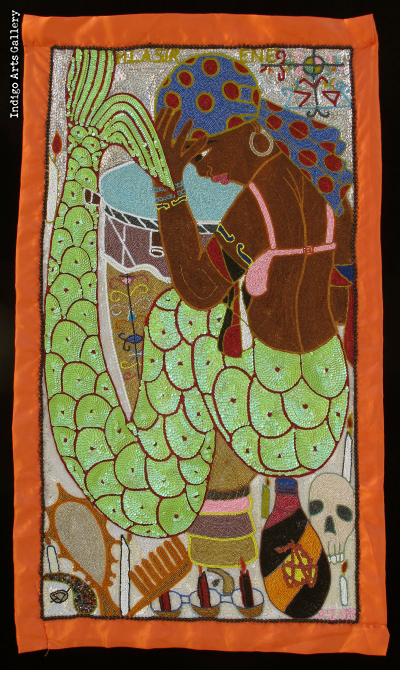

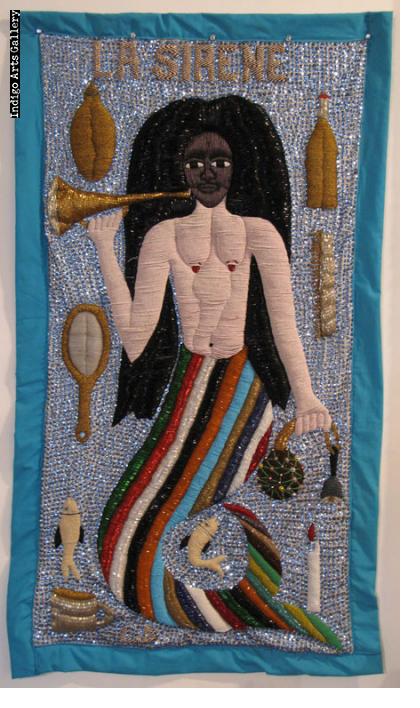

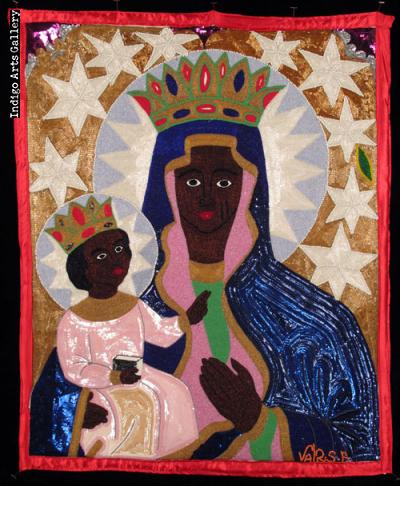

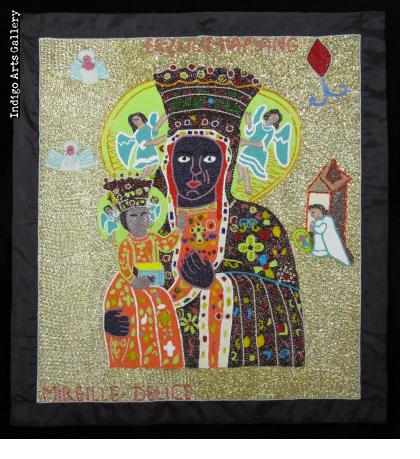

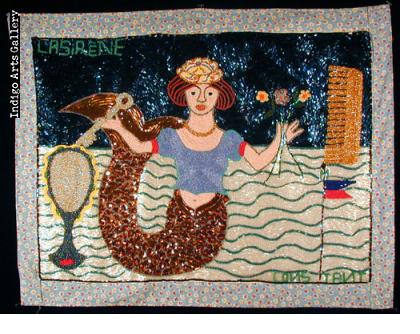

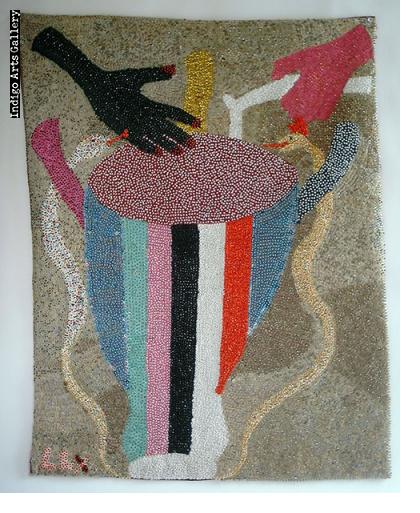

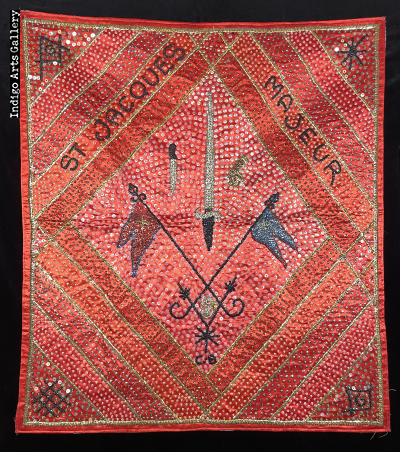

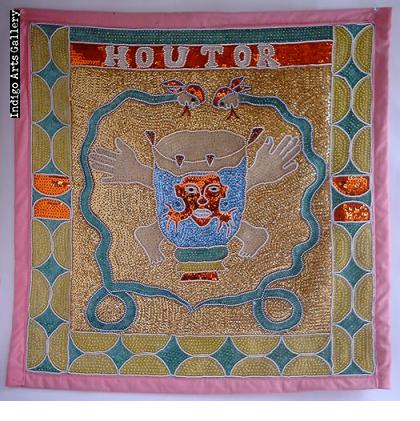

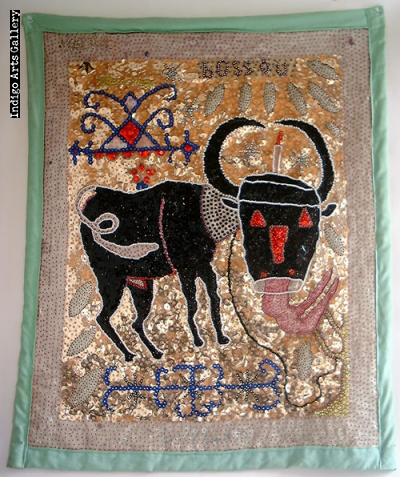

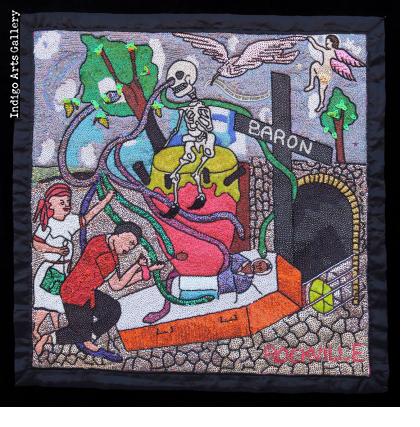

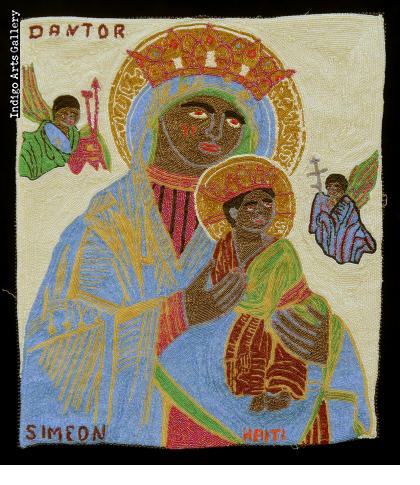

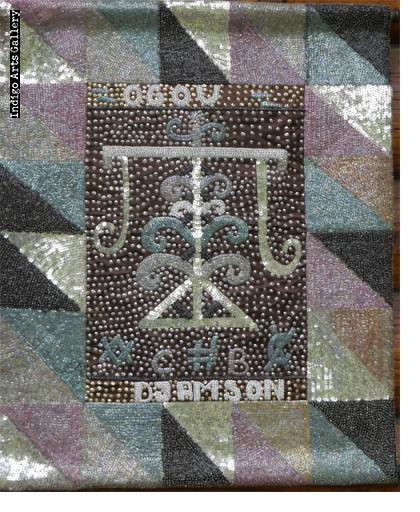

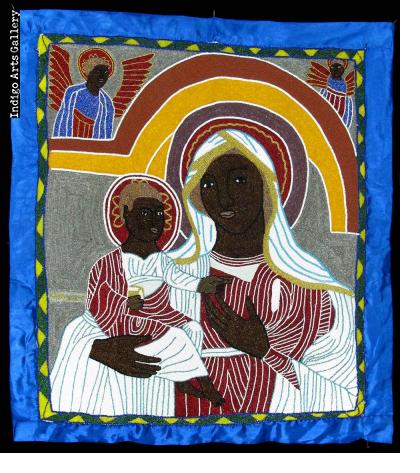

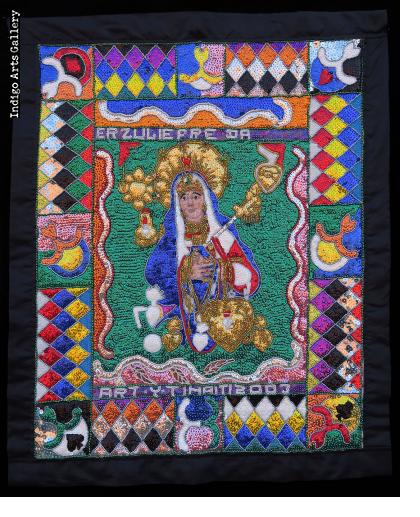

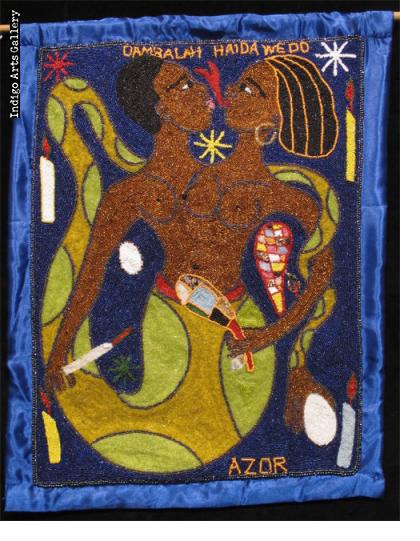

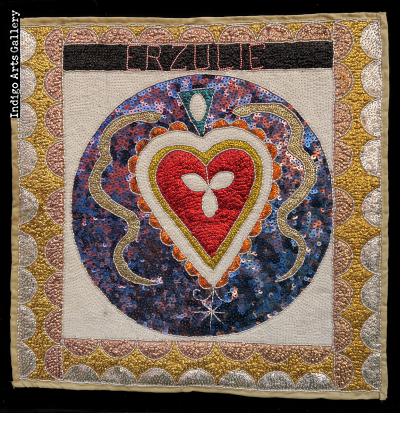

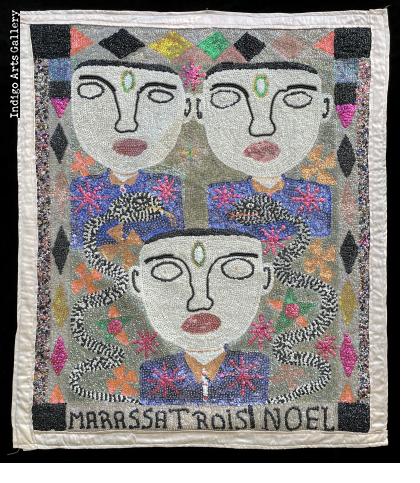

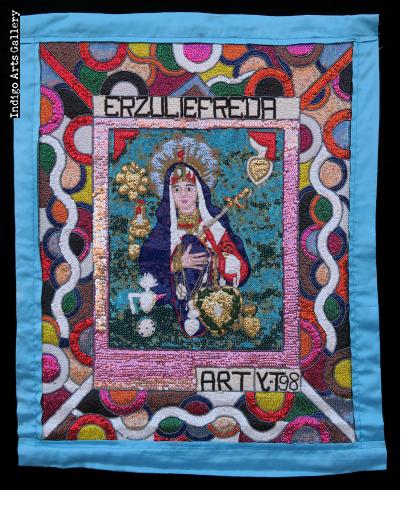

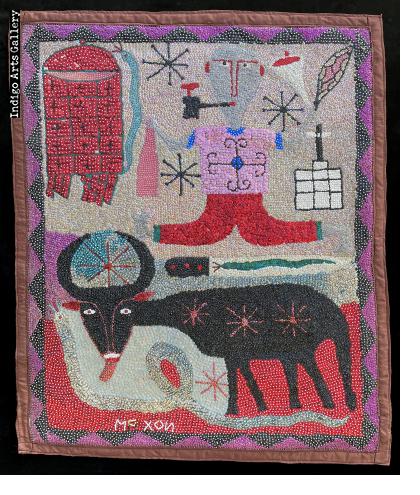

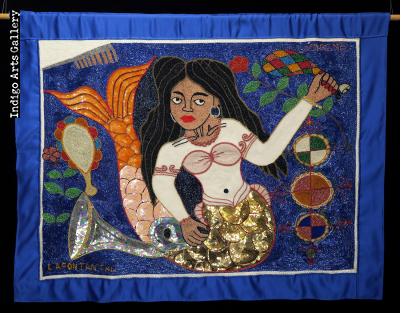

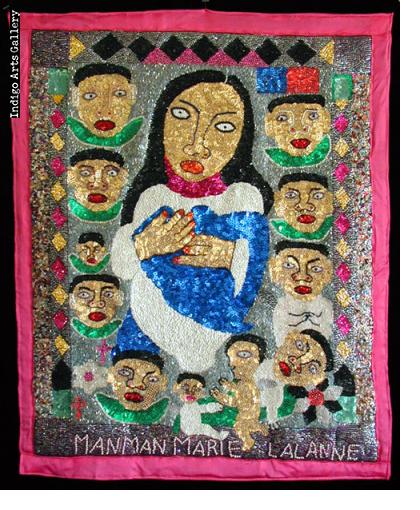

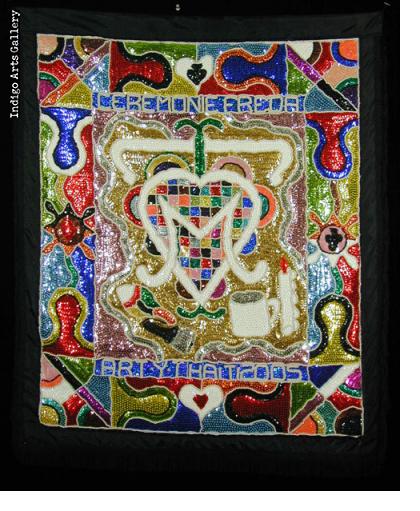

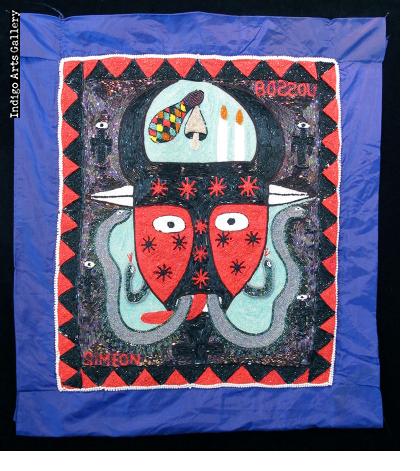

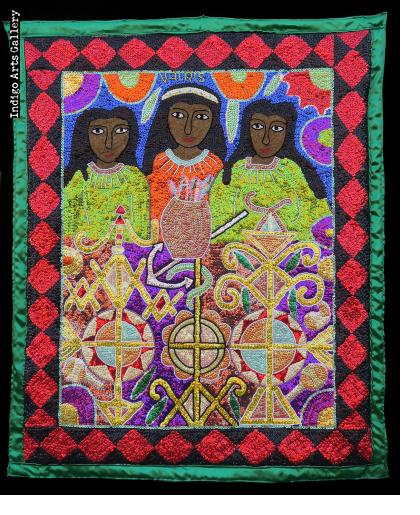

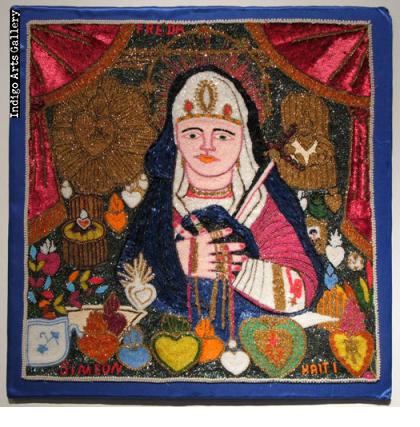

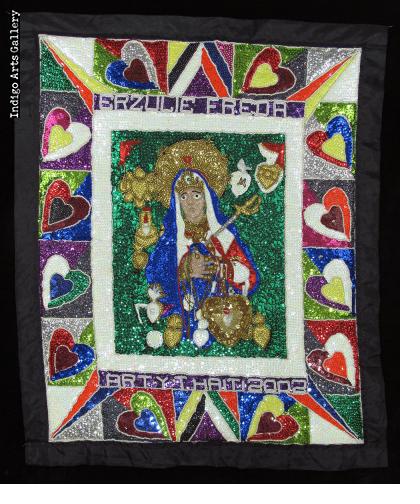

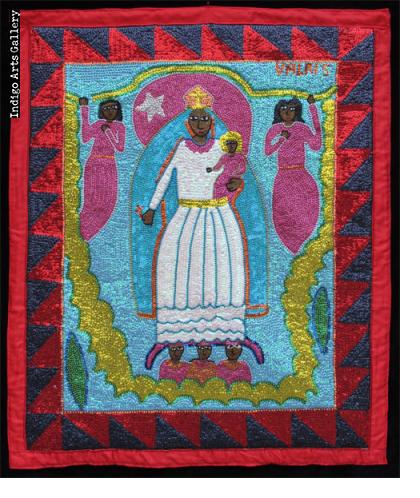

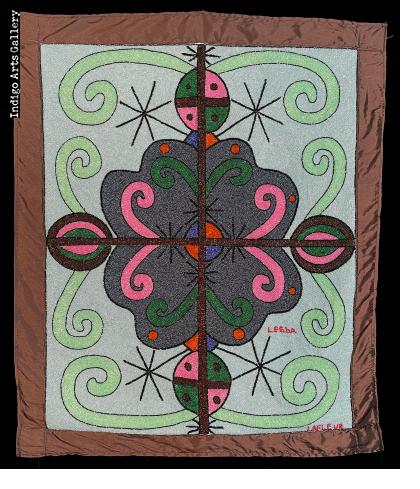

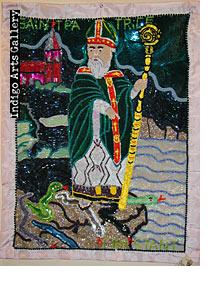

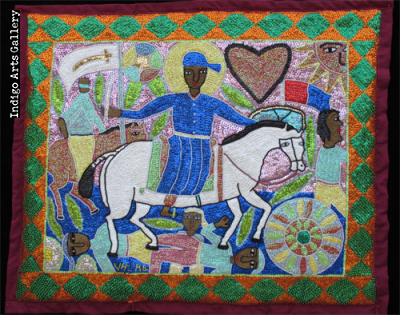

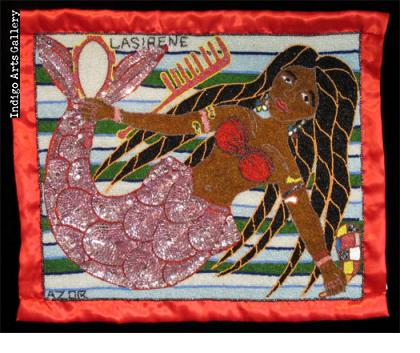

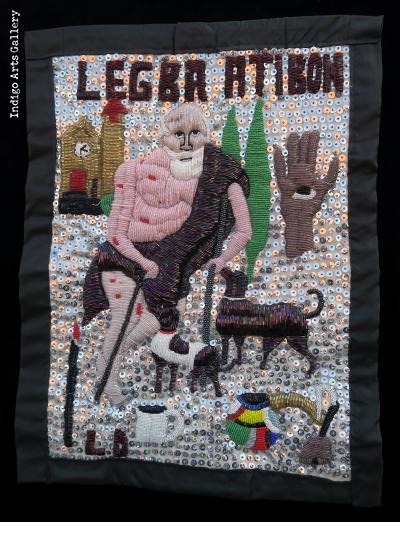

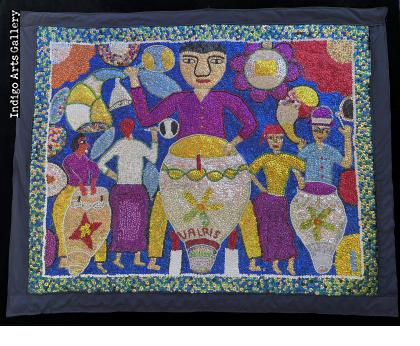

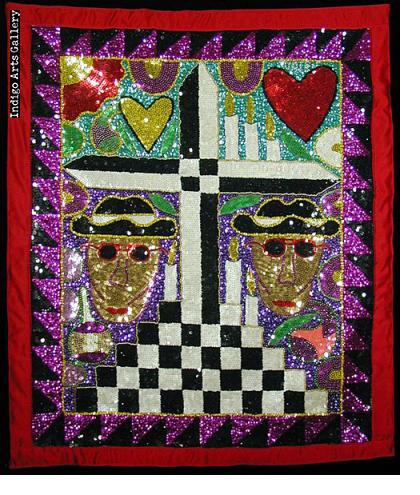

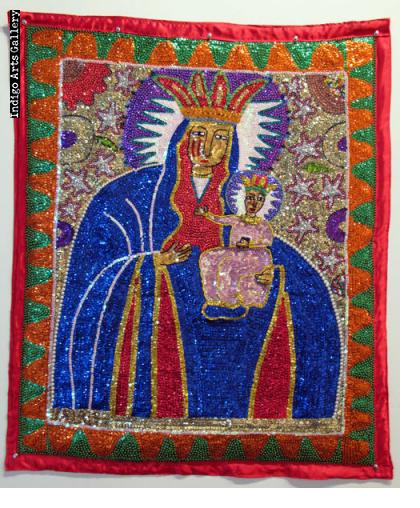

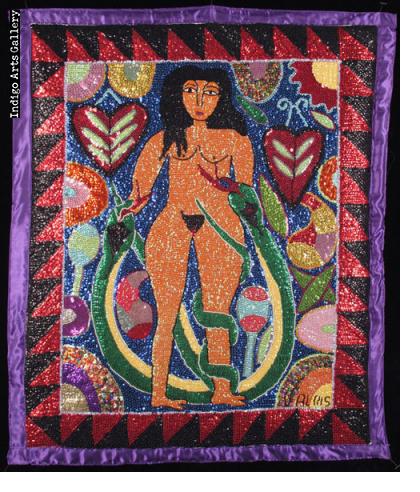

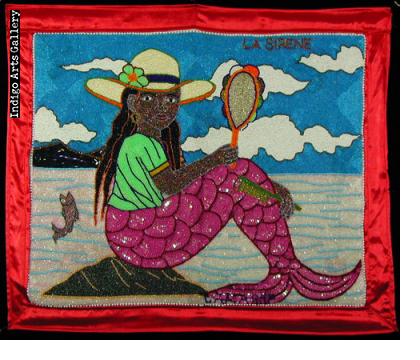

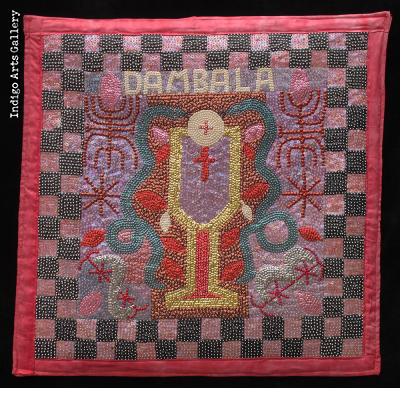

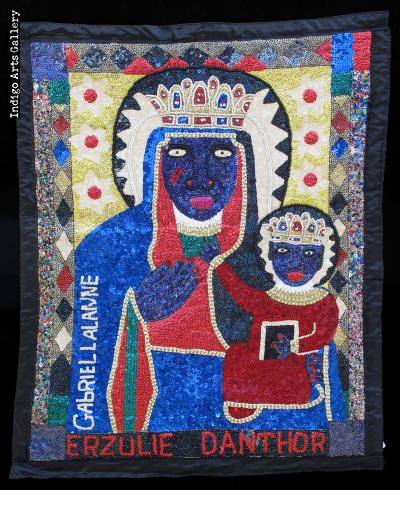

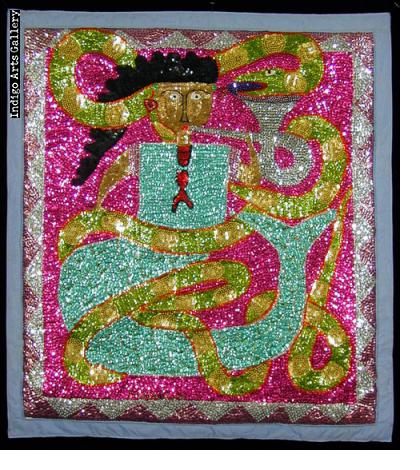

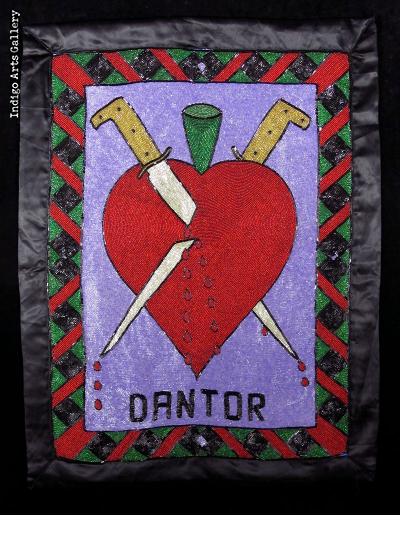

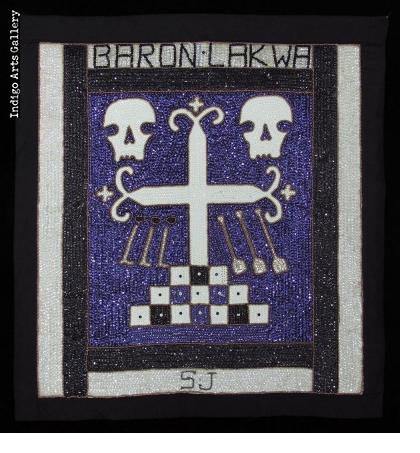

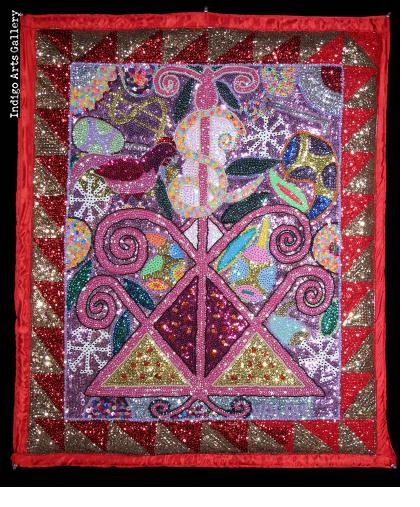

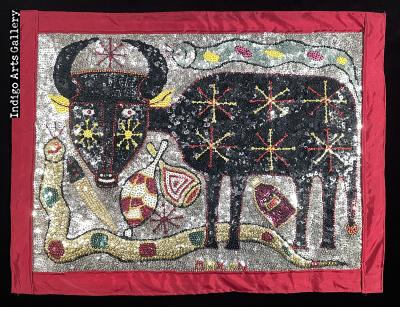

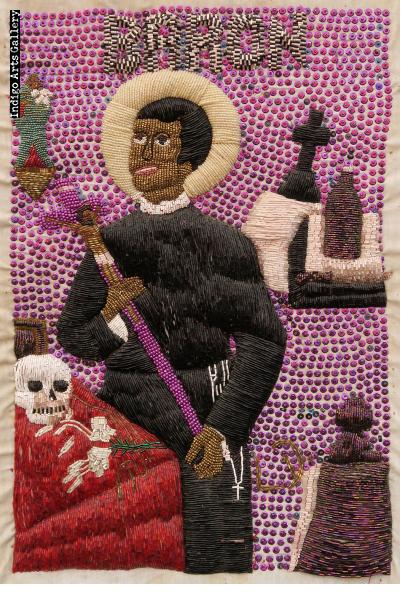

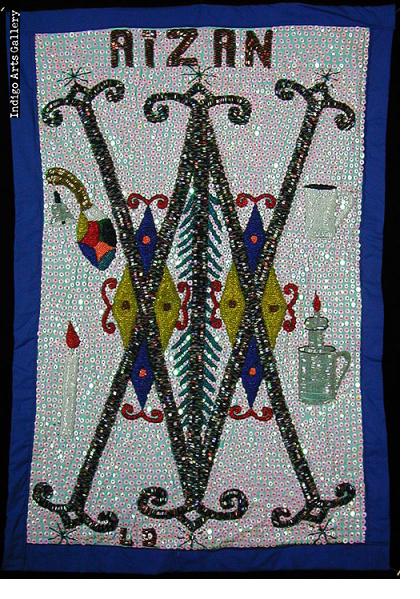

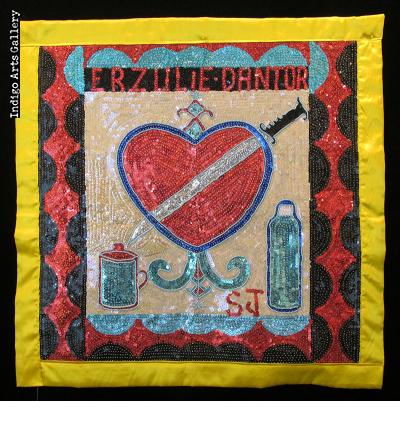

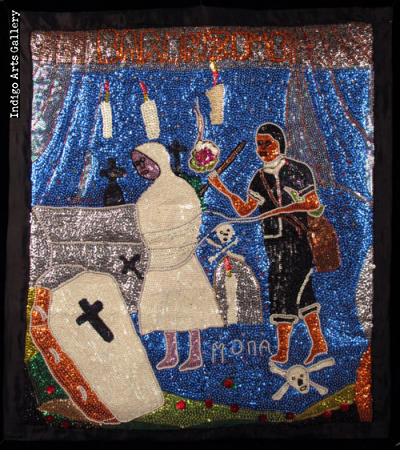

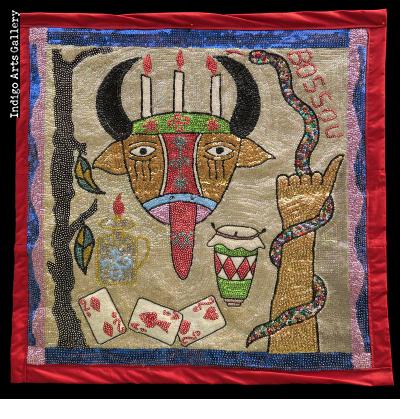

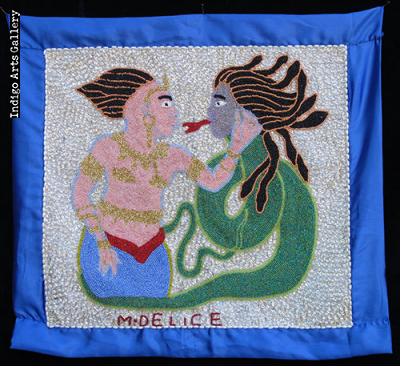

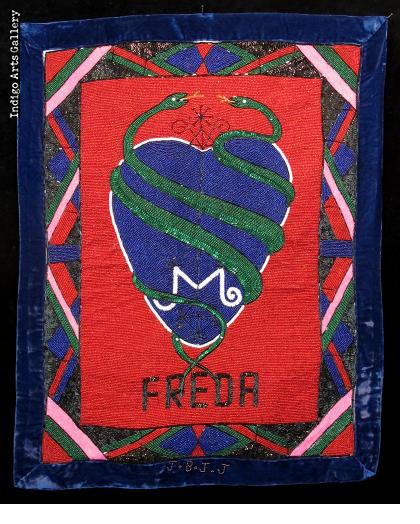

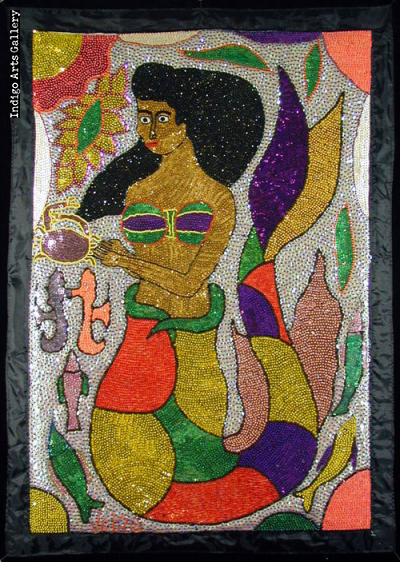

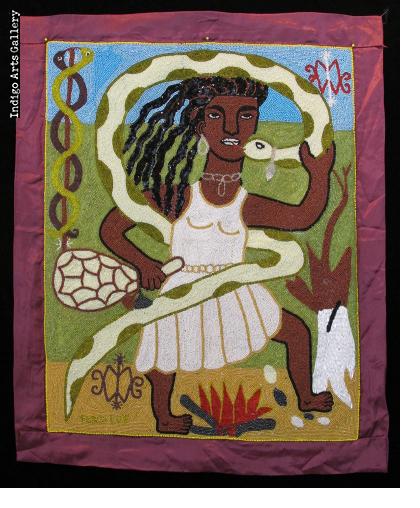

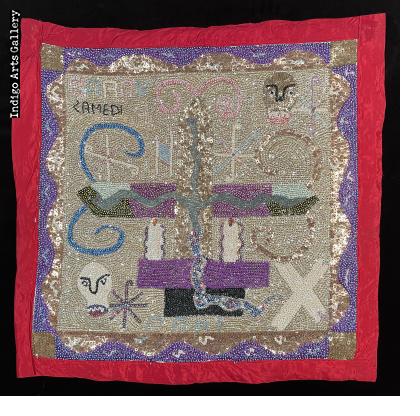

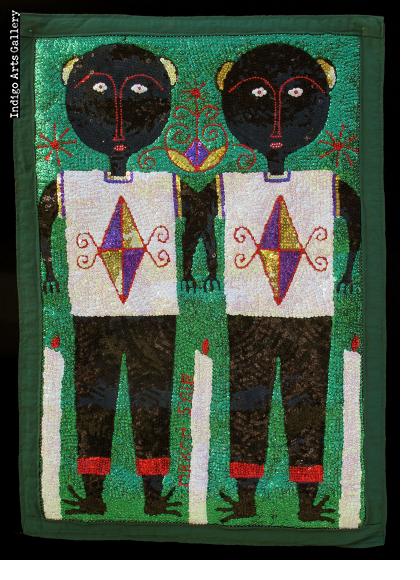

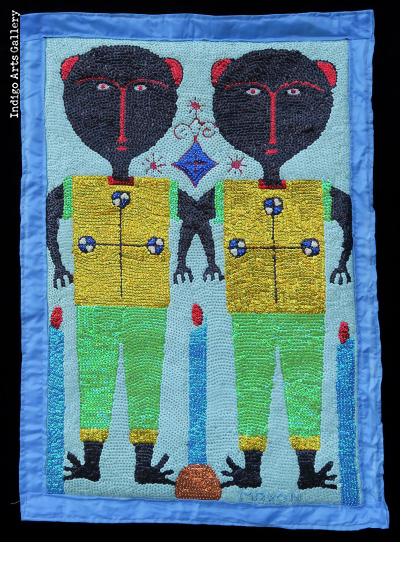

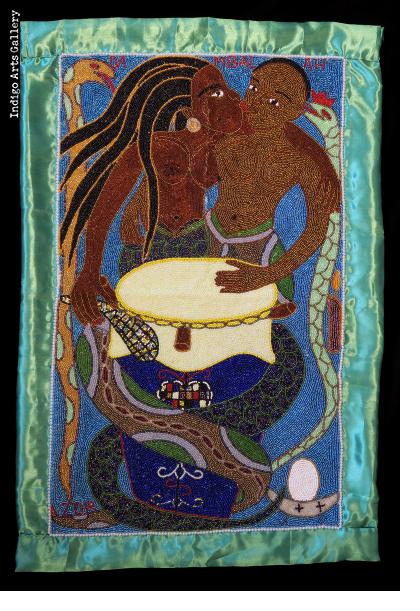

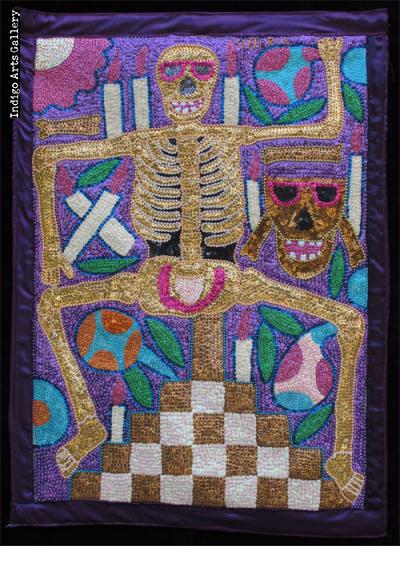

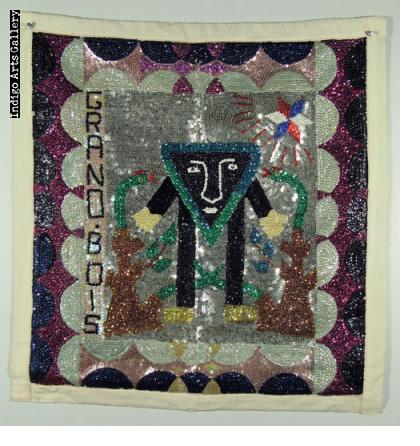

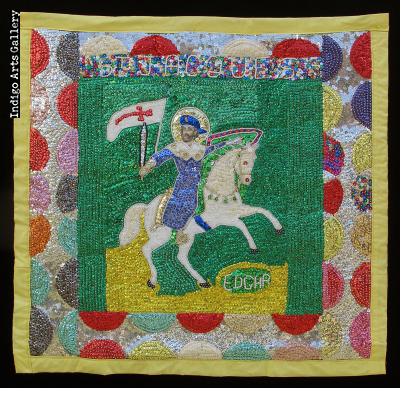

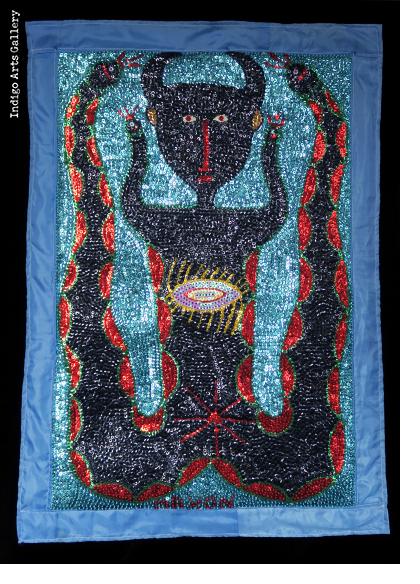

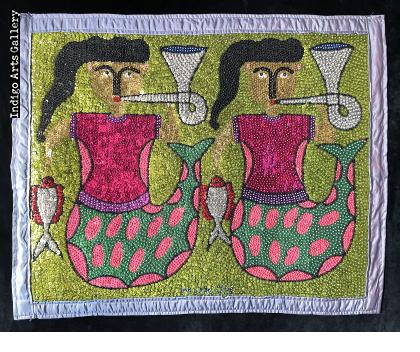

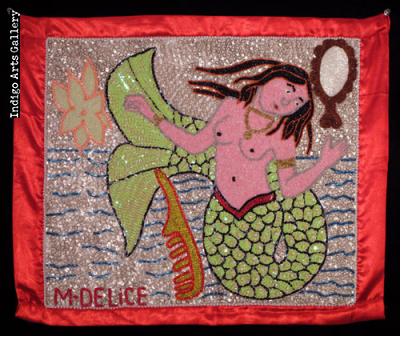

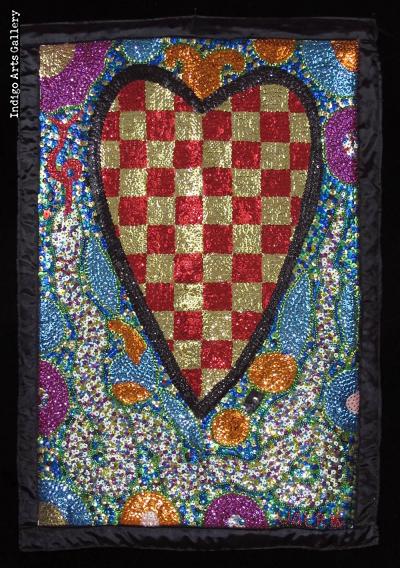

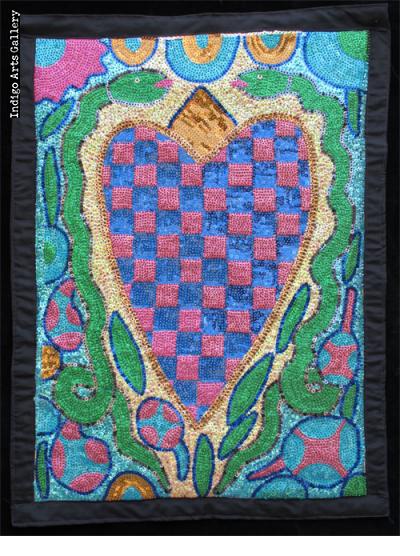

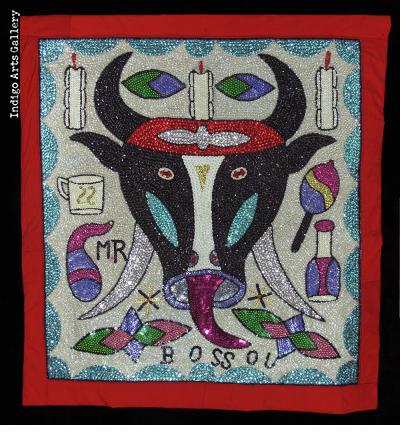

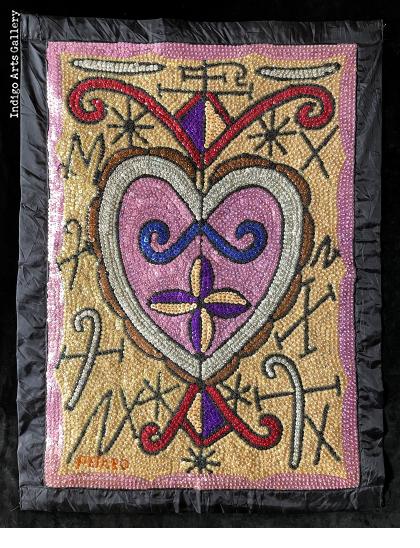

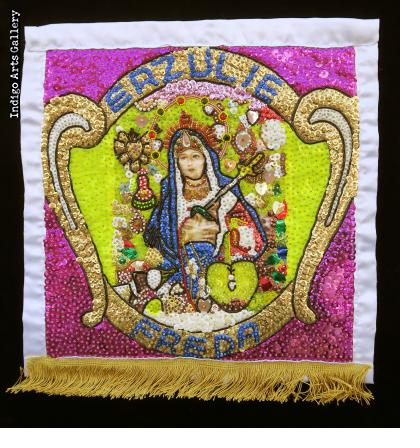

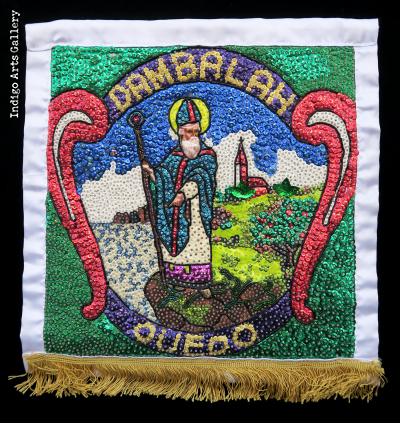

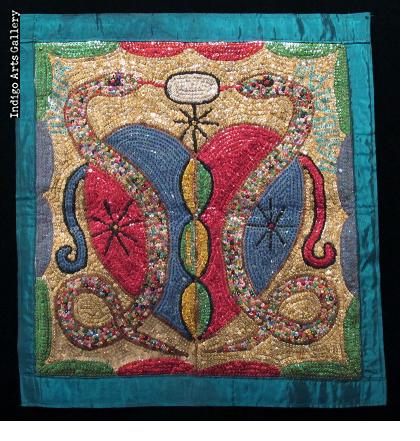

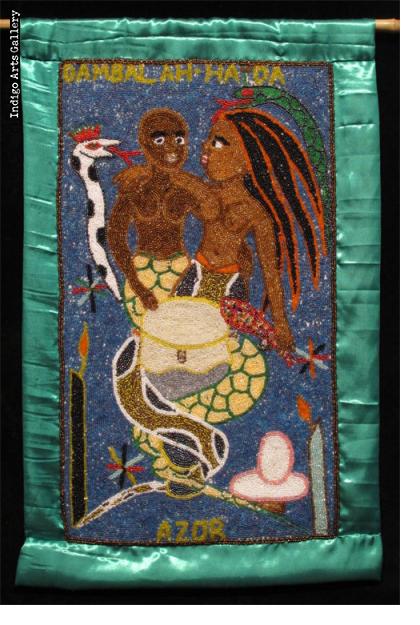

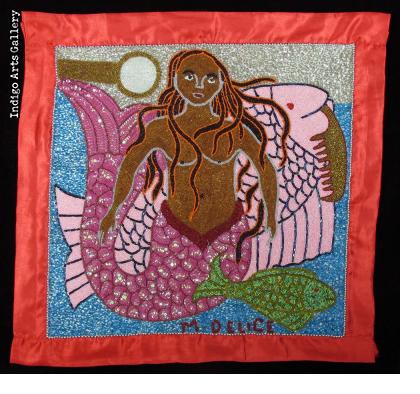

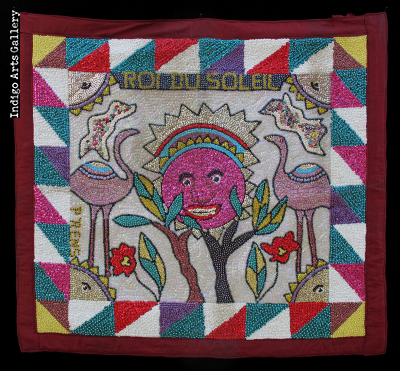

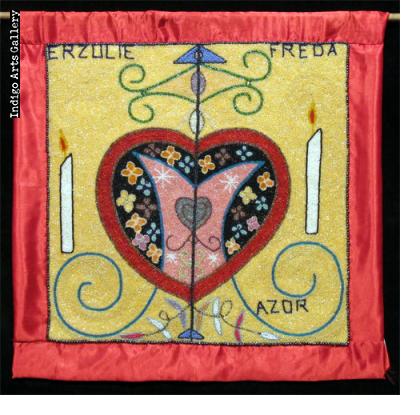

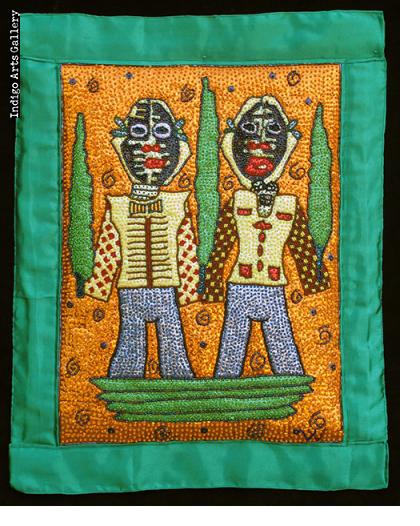

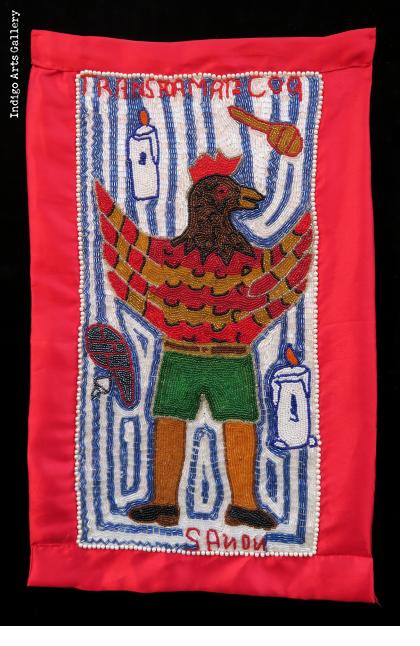

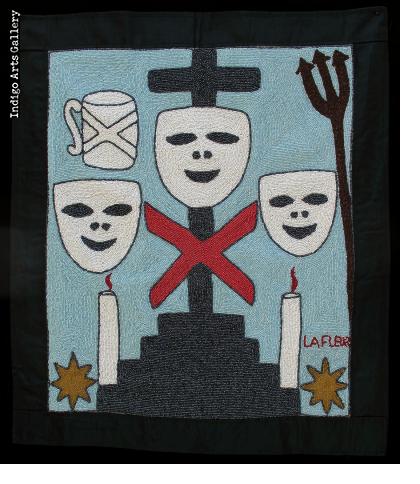

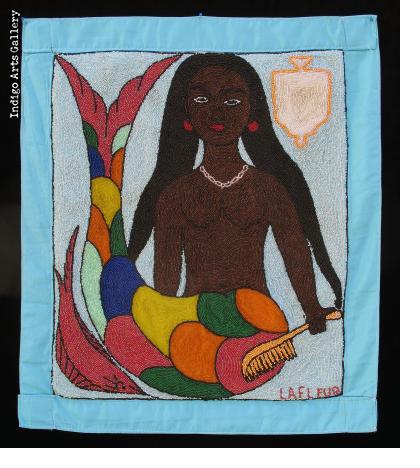

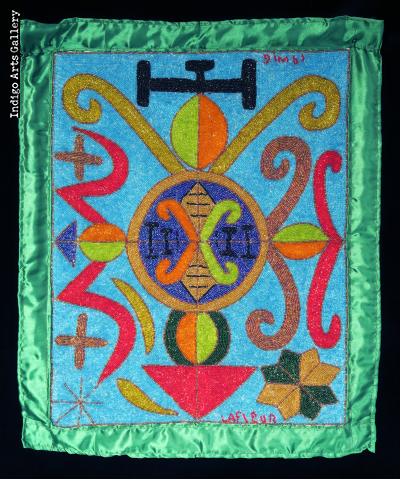

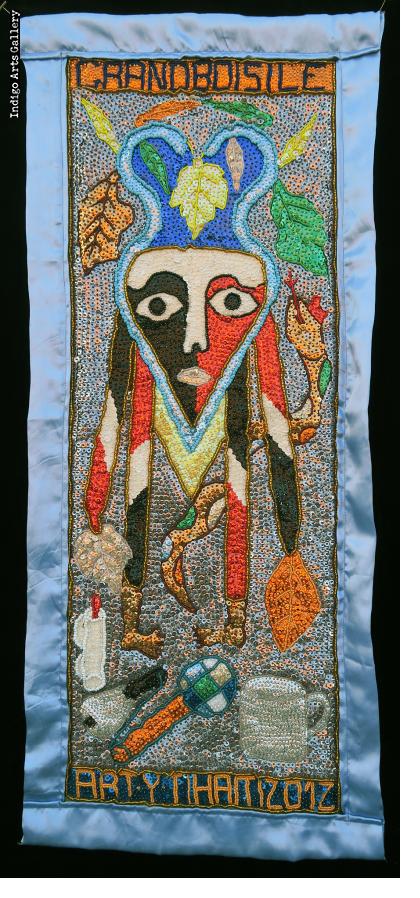

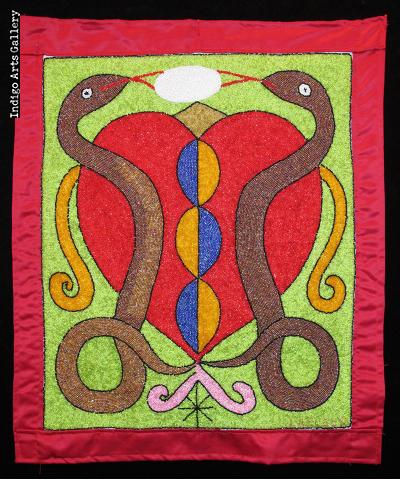

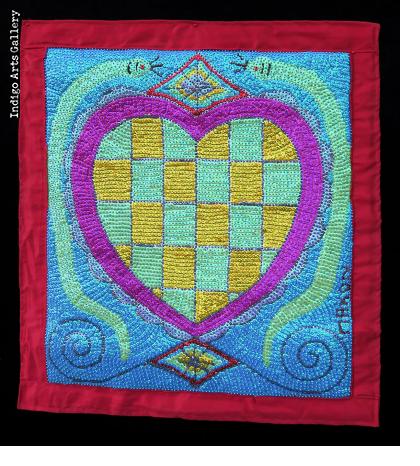

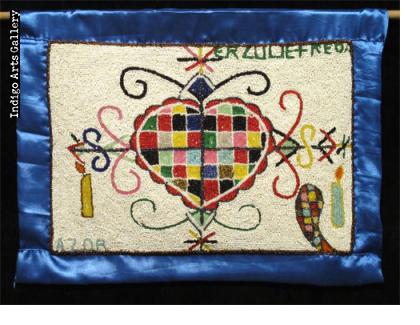

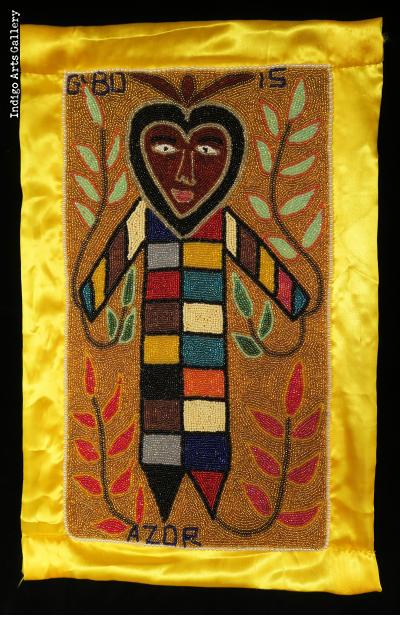

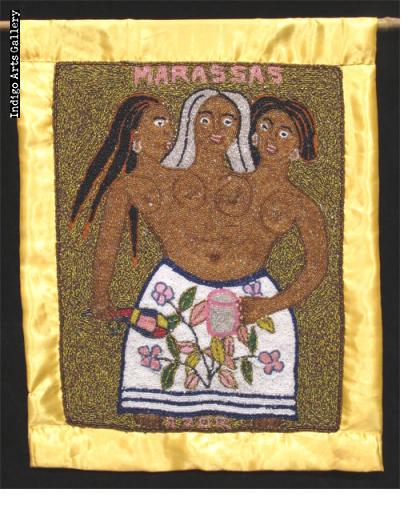

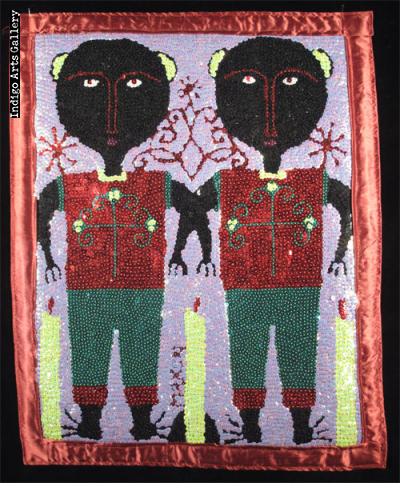

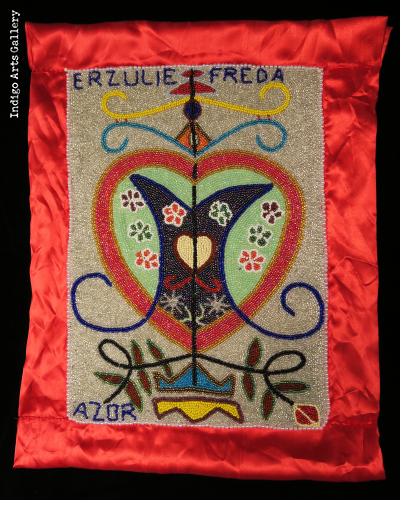

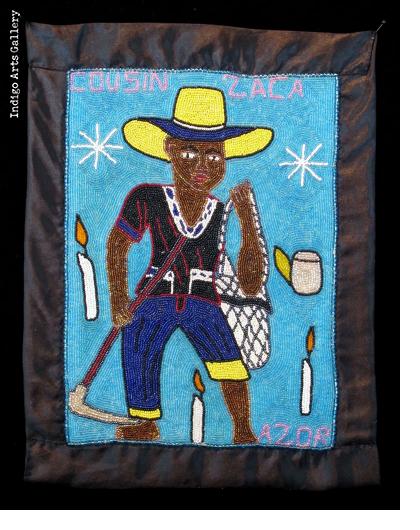

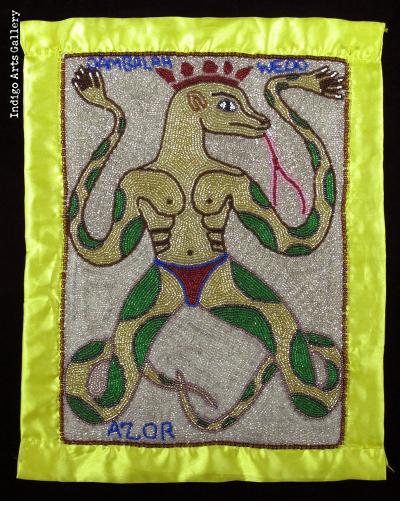

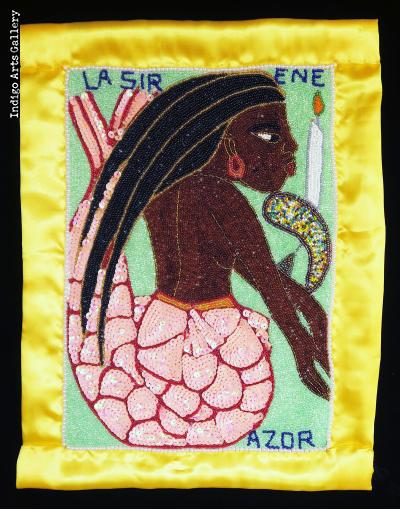

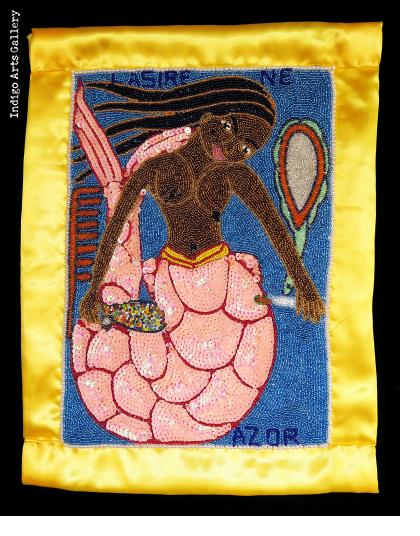

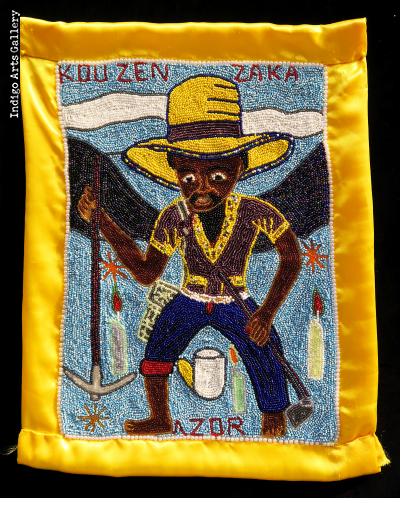

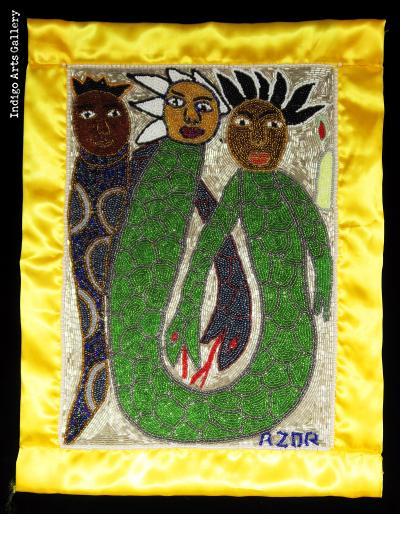

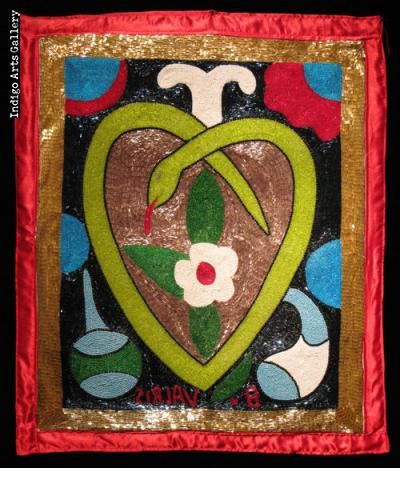

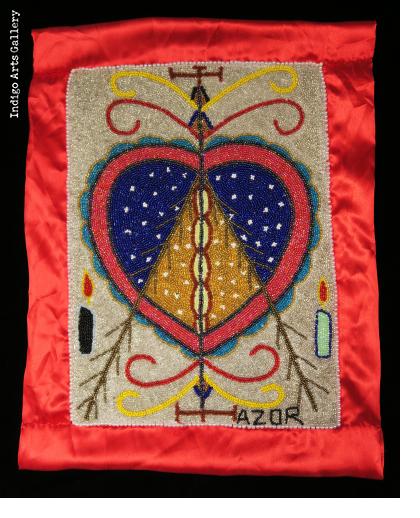

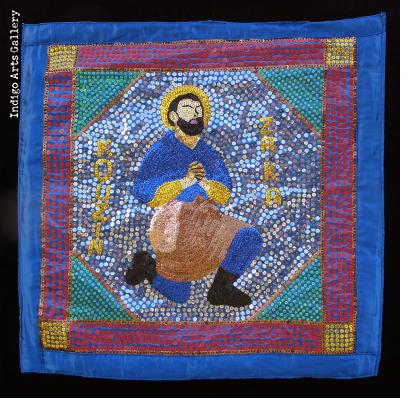

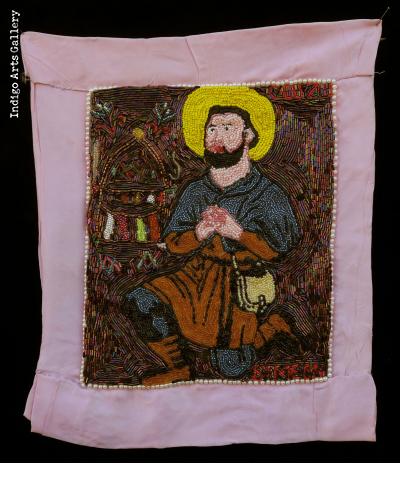

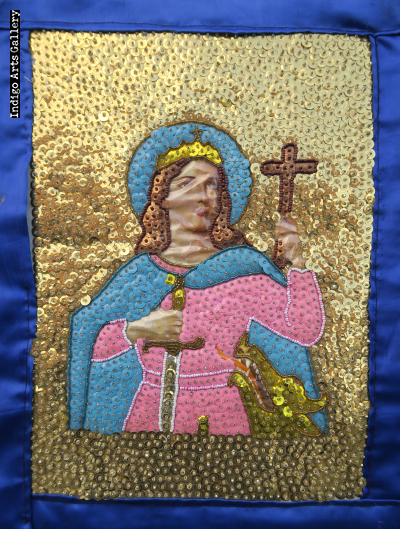

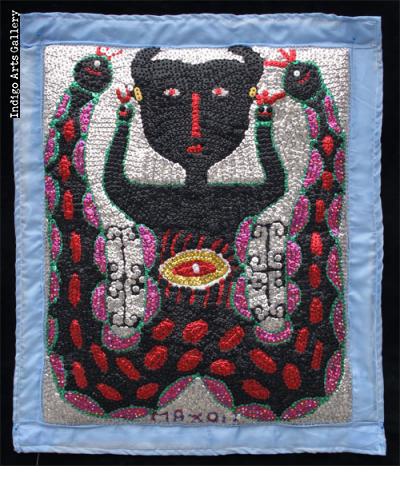

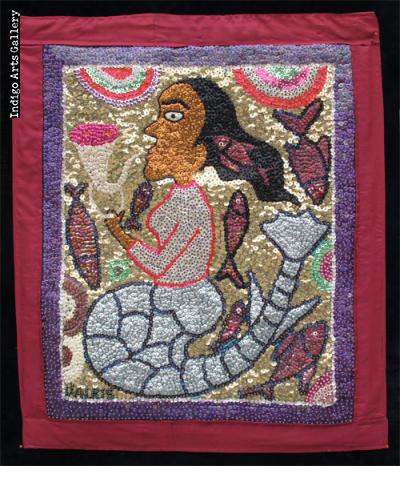

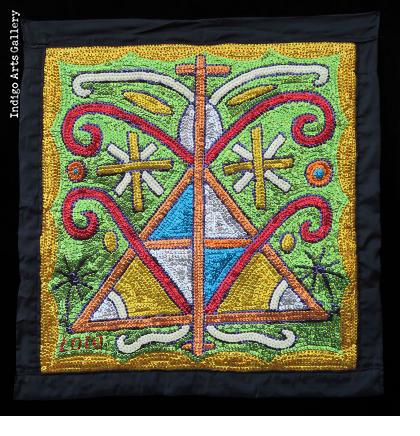

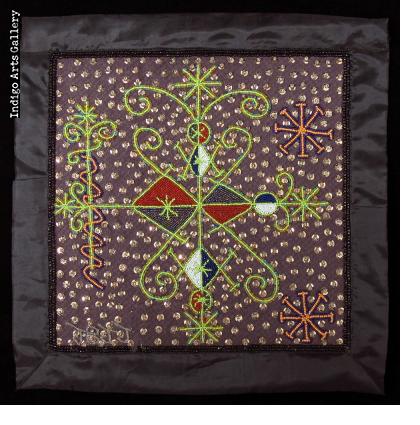

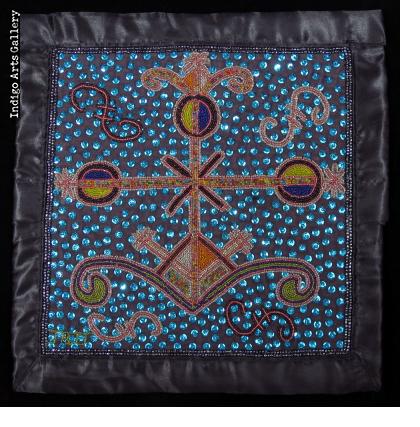

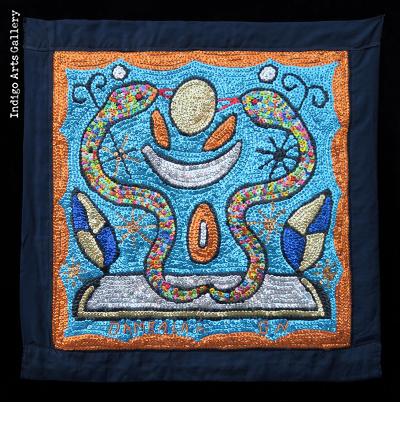

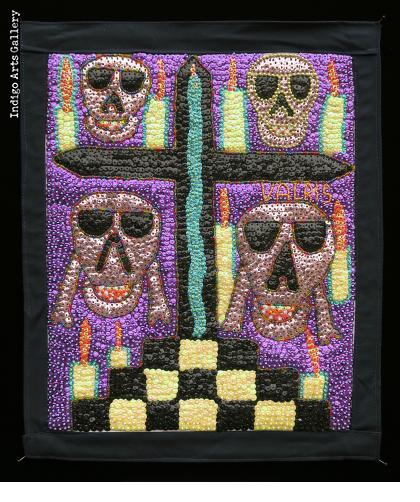

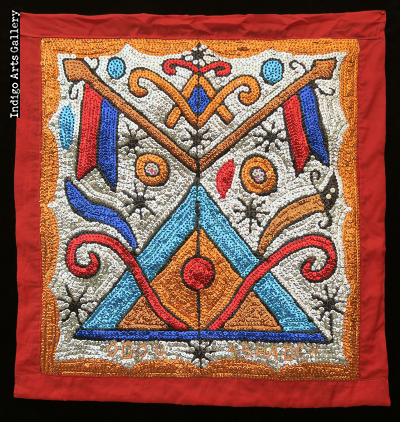

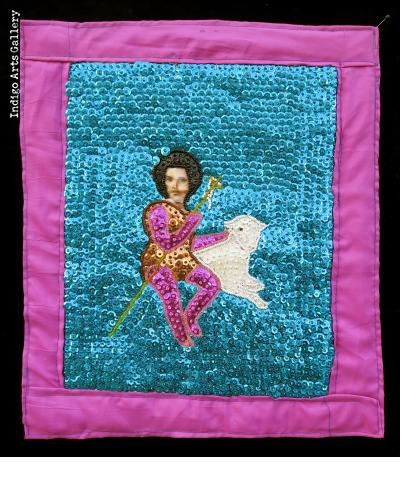

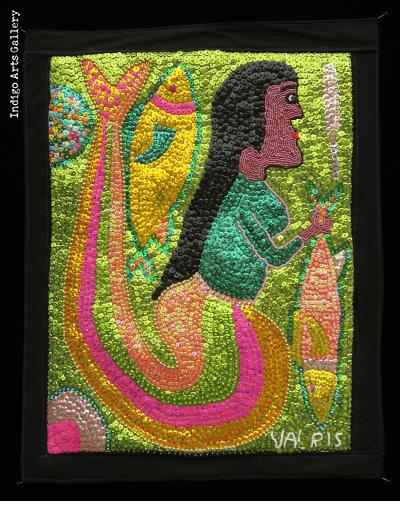

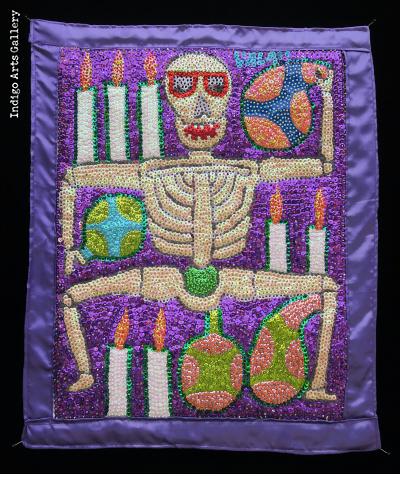

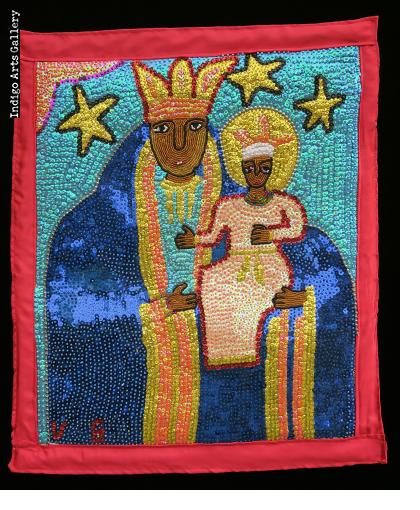

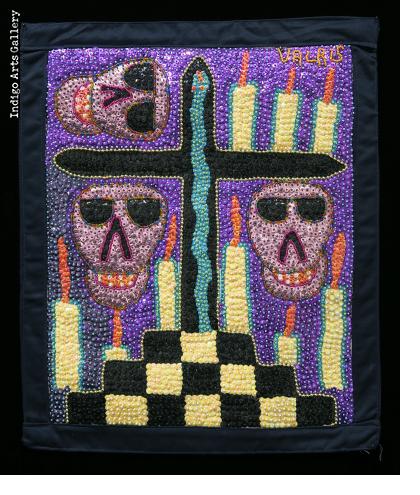

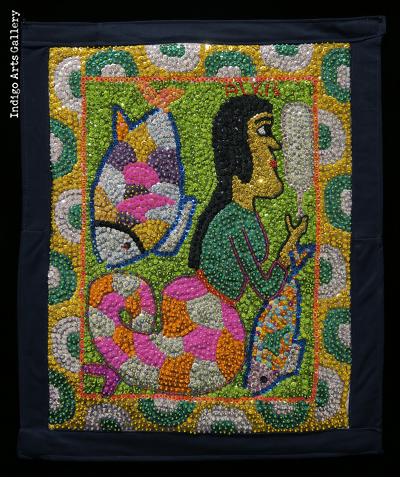

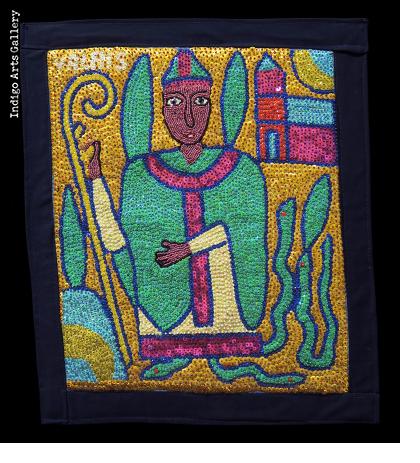

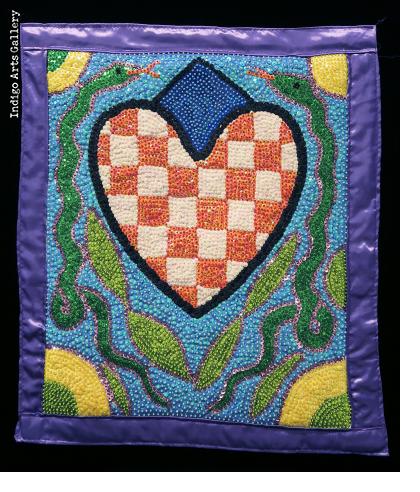

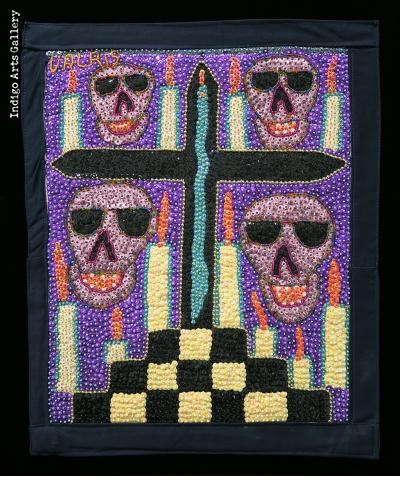

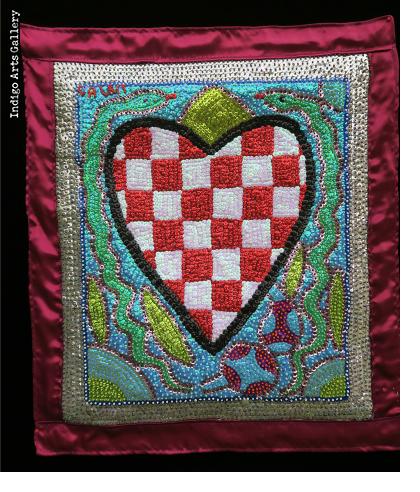

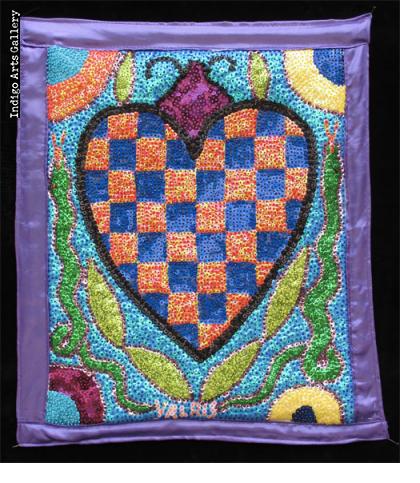

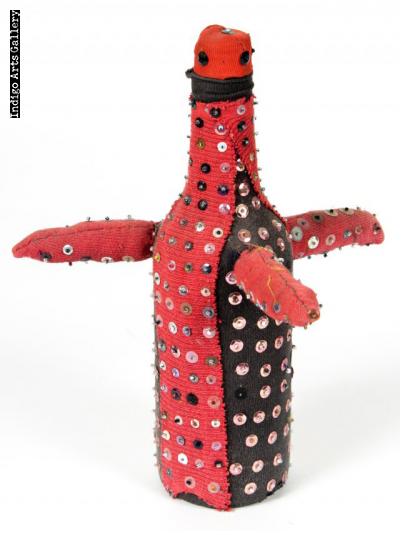

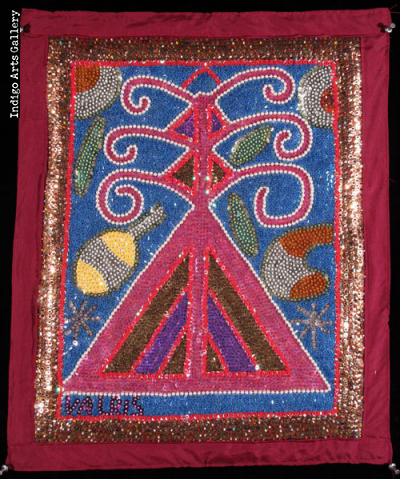

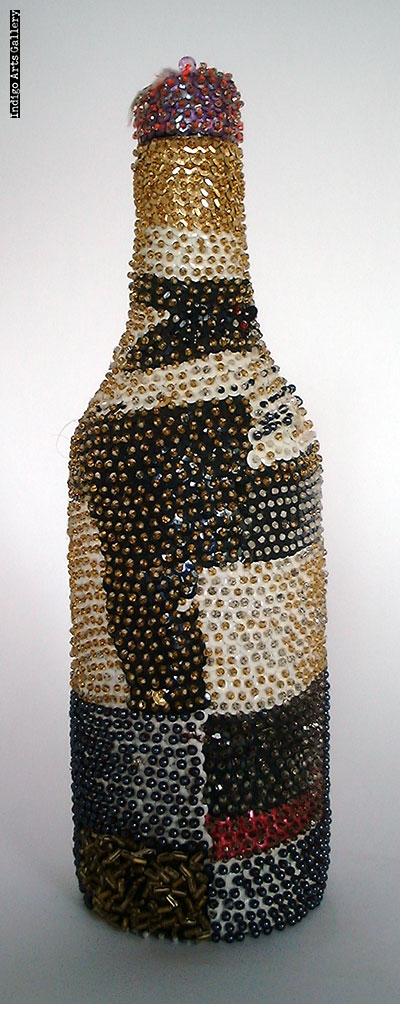

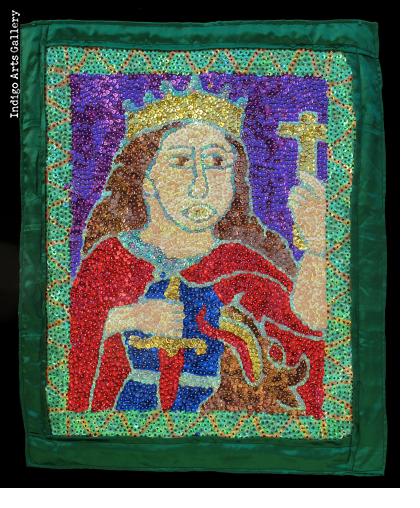

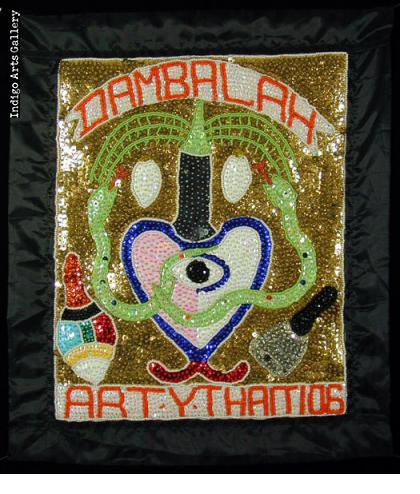

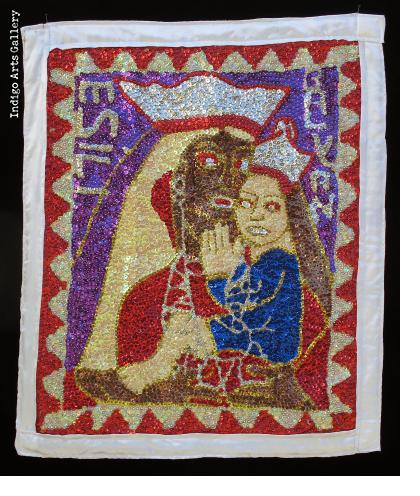

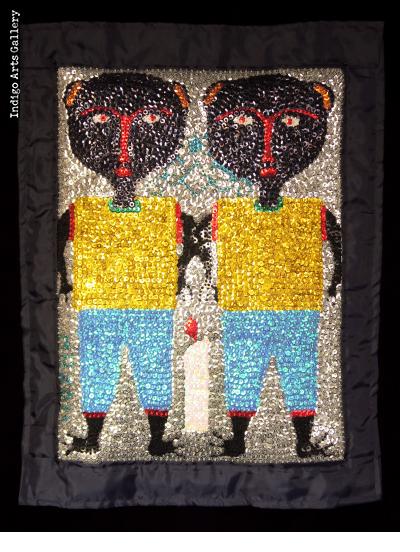

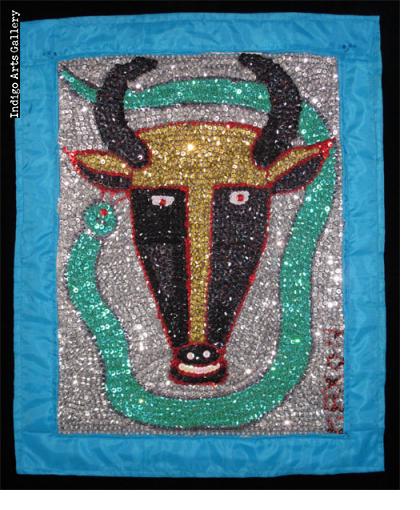

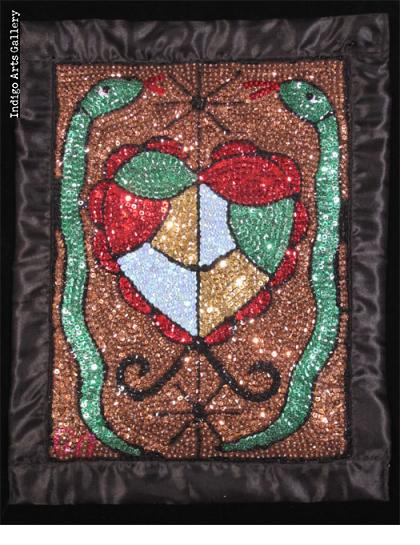

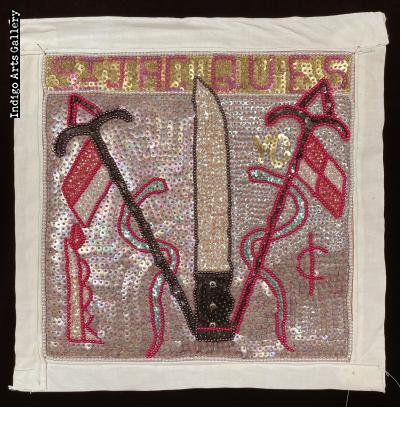

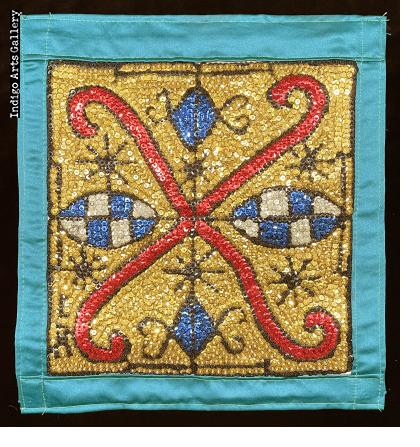

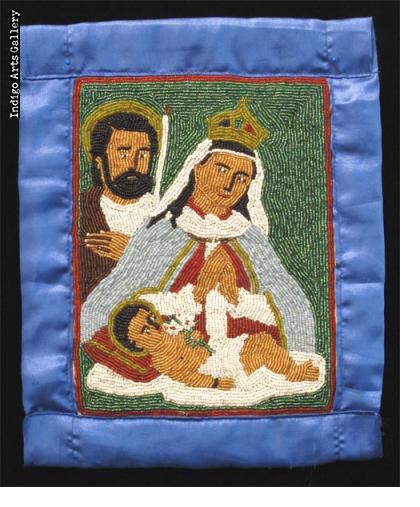

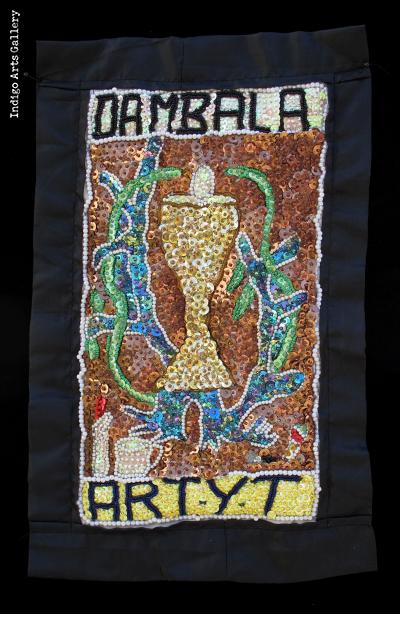

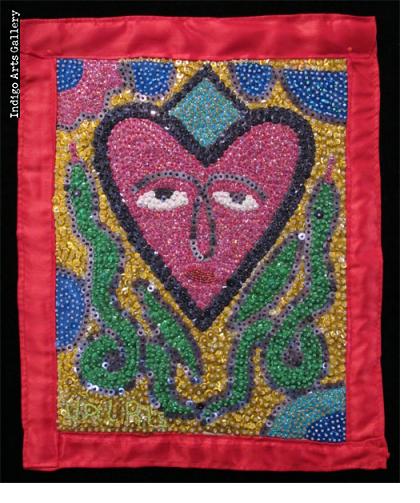

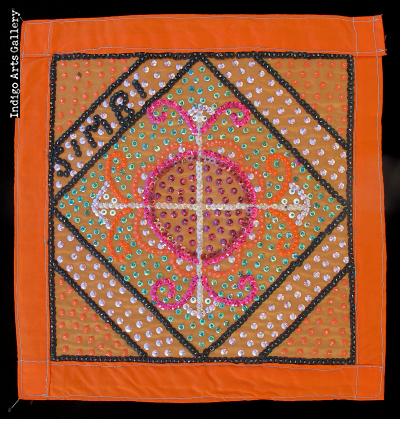

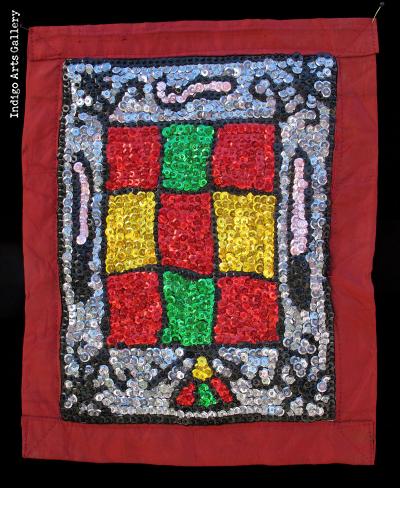

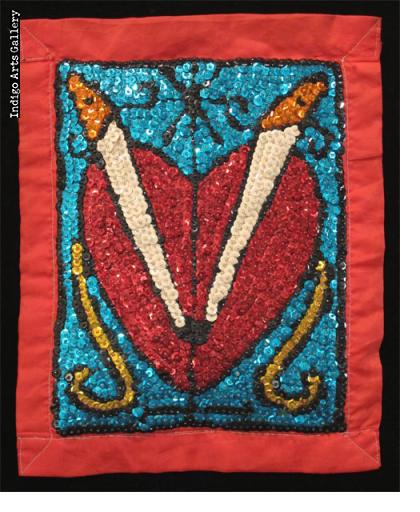

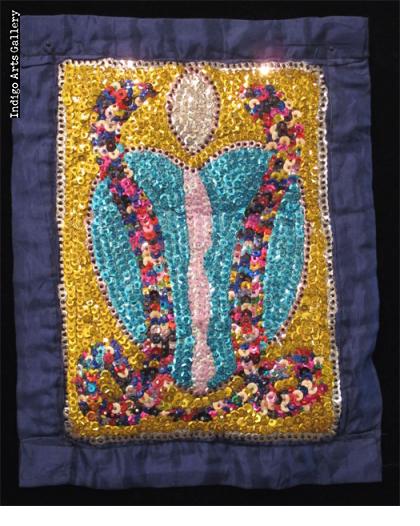

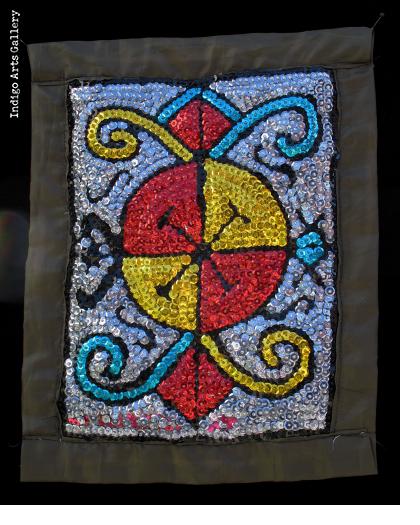

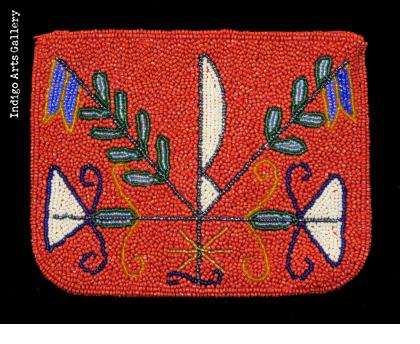

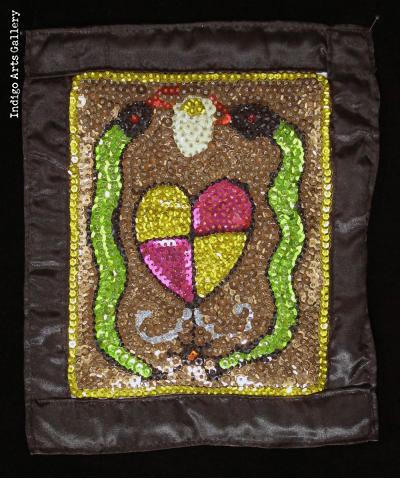

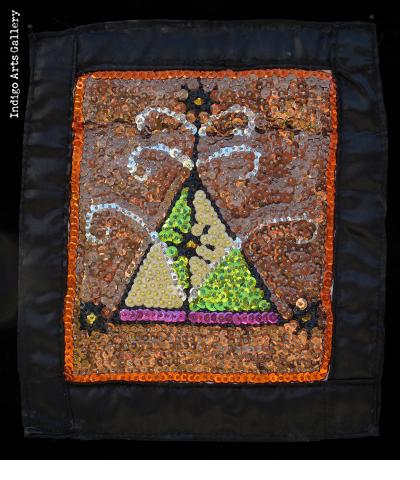

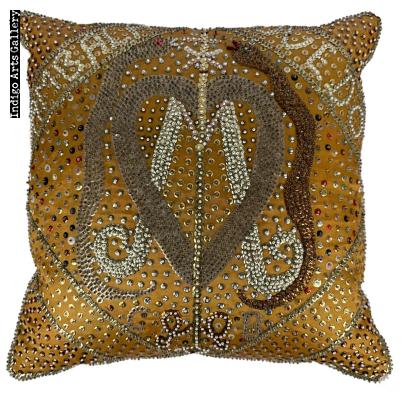

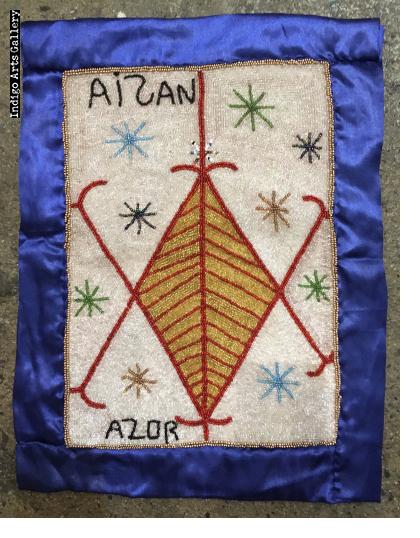

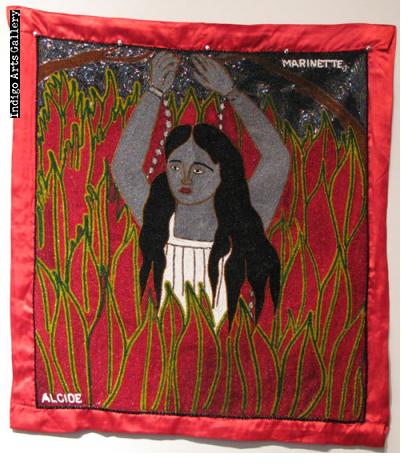

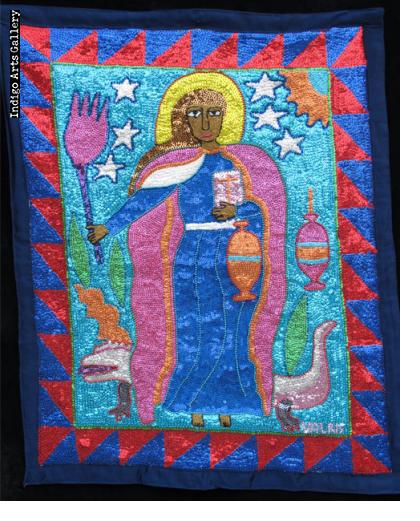

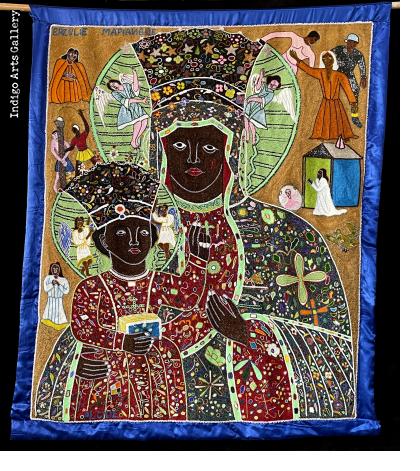

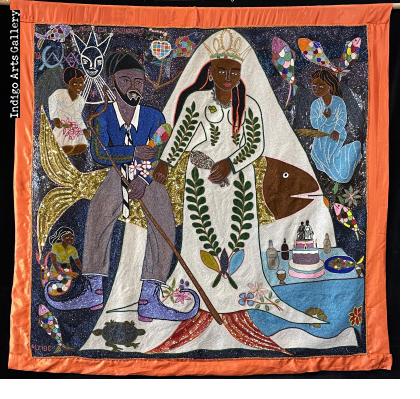

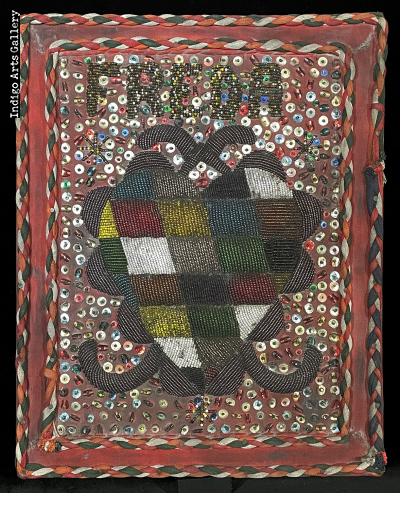

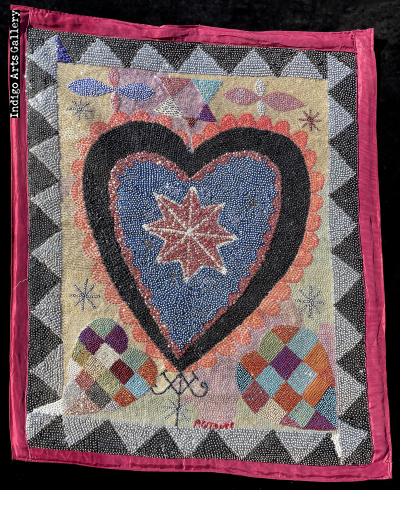

Doubtless the most spectacular Haitian art form is the sequin-covered Drapo Vodou or "Voodoo Flag". Vodou banners derive directly from the practice of the Vodou religion. Vodou is a syncretism of the traditional African religions brought to Haiti by slaves, with the Catholicism of their former masters. The banners are traditionally the work of practicing vodou priests and their followers. They are displayed in the vodou sanctuaries and are carried at the commencement of a ceremony. Each flag depicts the vévé symbol or image of the loa to which it is devoted. These include: Erzulie Freda the female deity, “goddess of love” associated with the Virgin Mary; Ogou, deity of iron and war, associated with St. Jacques; La Sirene and Agoue, the female and male deities of the sea; Legba, gatekeeper and lord of the crossroads, associated with St. Peter; Azaka, the farmer, associated with St. Isidore; Bossou, the bull; Damballah, symbolized by the snake, and paired with St. Patrick; and Baron Samedi, keeper of the cemetery and one of the Ghedes, lords of the underworld. The flags are made of shiny silk fabrics to which have been sewn a brilliant mosaic of sequins and beads. A full-size banner typically contains 18,000 to 20,000 sequins and may take ten days to complete.

While the origins of this ritual art form have been traced back several hundred years, to sources as divwrse as African textiles and French regimental flags, the present form of the vodou flag may date to only the 1950’s. But in the 1970’s and 1980’s, following on the celebrated “Haitian renaissance” in painting and sculpture, the vodou banner also came to the attention of collectors and critics. Artists were able to sell directly to tourists (until tourism essentially ended in the mid-1980’s), and an art market developed for flags as well.

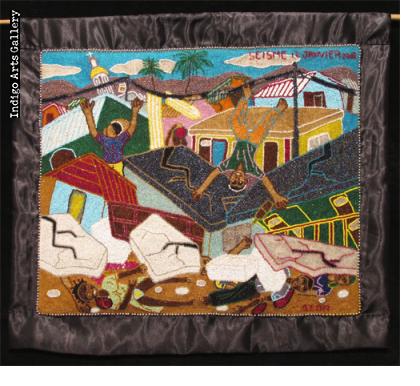

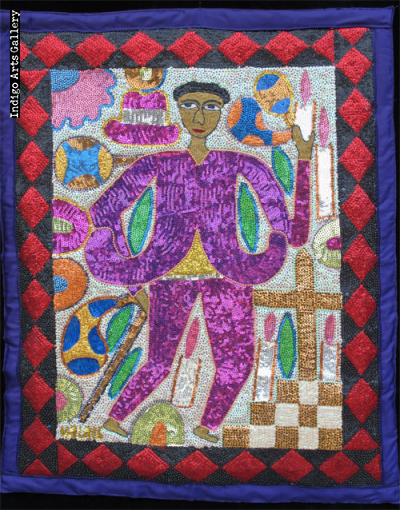

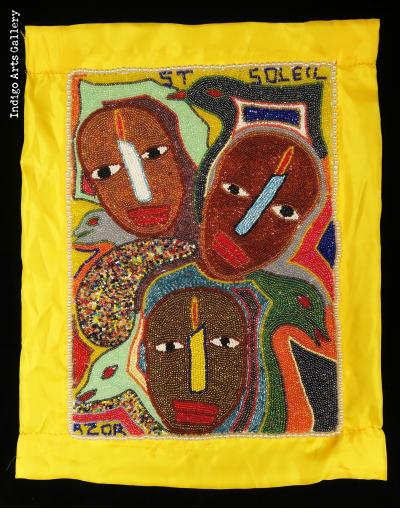

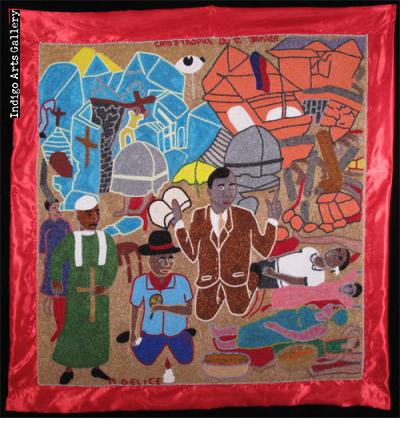

Among the more traditional practitioners of the art who are still working include Sylva Joseph, Clotaire Bazile, and Yves Telemac. The interest of collectors (and collaboration with artists from abroad such as Tina Girouard and Alison Saar) spurred innovation in the medium, and such artists as the late Joseph Oldof Pierre and Antoine Oleyant brought the art form to a new plane of creativity. Since the death of Antoine Oleyant in 1992, and in spite of the hardships of the political strife and economic embargo in Haiti, other important sequin artists such as Eveland Lalanne, Roland Rockville, Petit Frere Mogirus, Maxon Scylla, and George Valris have come to prominence.

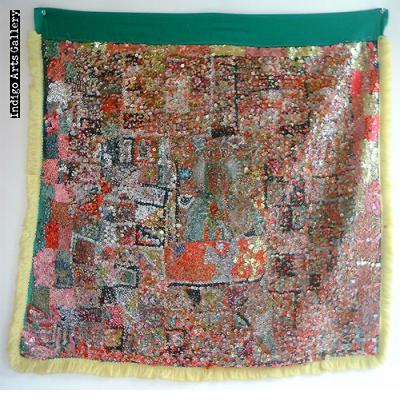

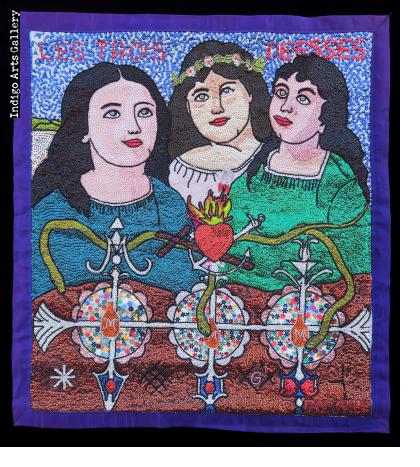

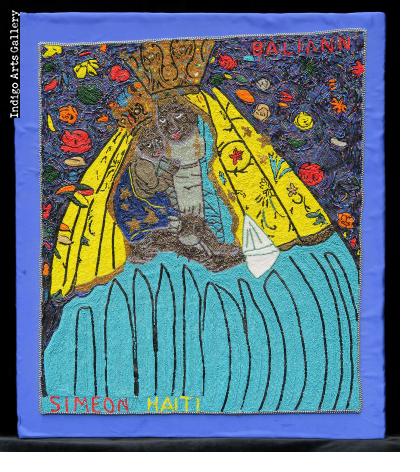

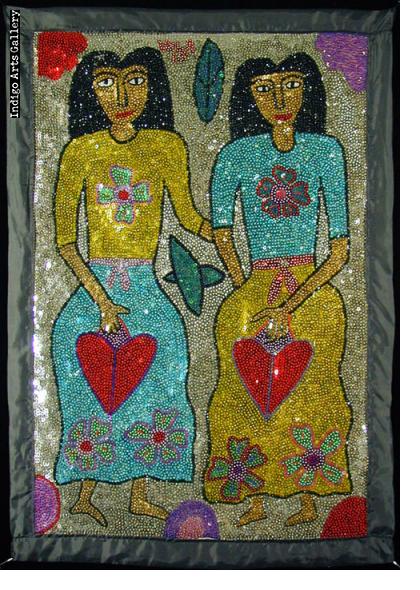

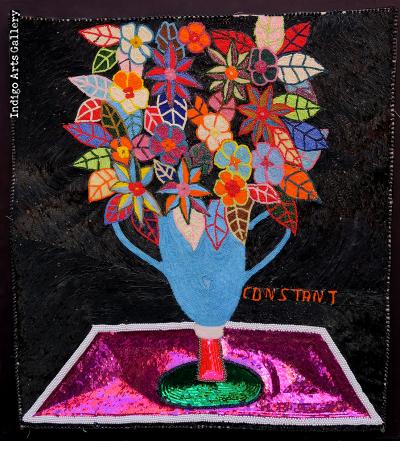

The most recent and exciting development in the art of Drapo is the emergence of the “wedding-dress factory artists”, such as Myrlande Constant, Evelyn Alcide, Roudy Azor and the late Amina Simeon. These artists, several of whom had worked at a now-closed wedding-dress factory in Port-au-Prince, introduced techniques of dense and intricate beading and sequins to the art of the drapo. This allowed much finer detail of design and subtlety of color, and encouraged the introduction of more painterly techniques such as shading and perspective to the medium. What were once essentially sequinned religious icons have become ever more complex beaded mosaic paintings.