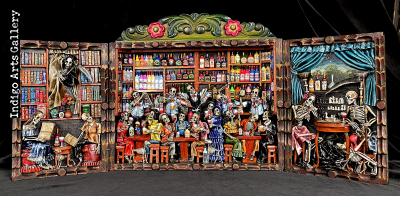

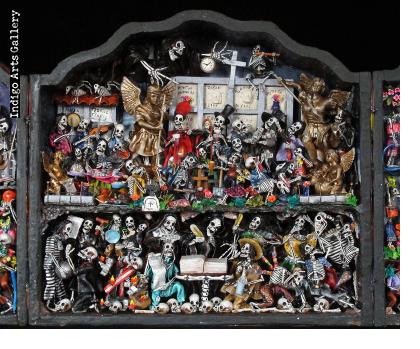

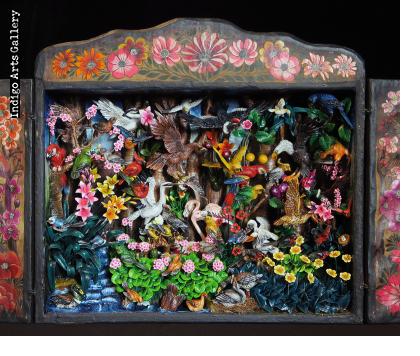

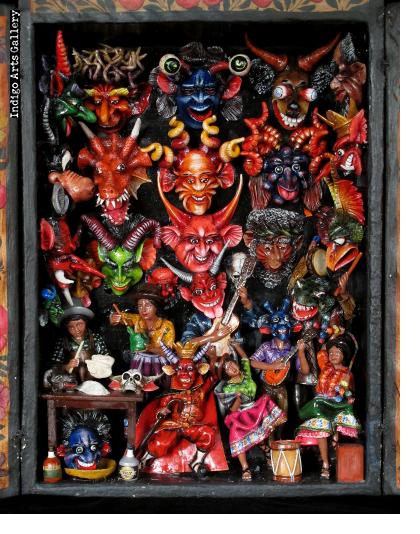

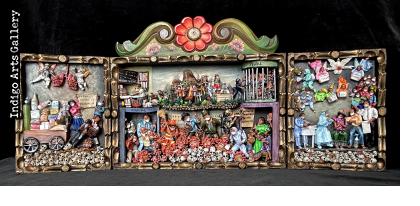

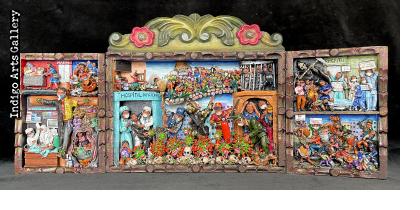

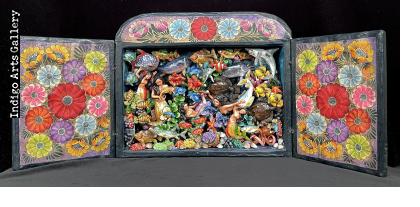

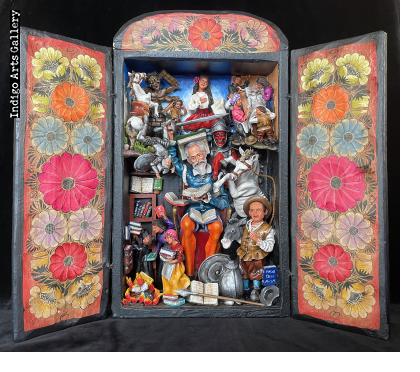

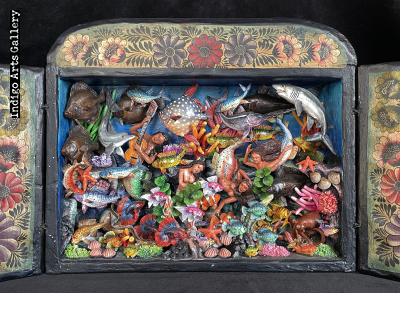

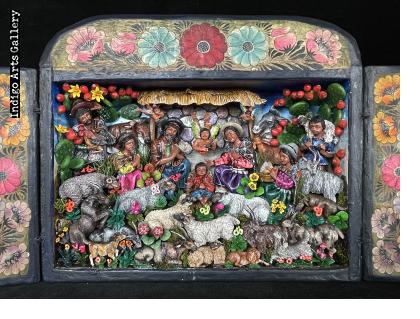

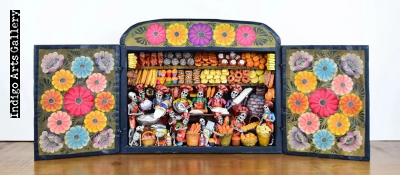

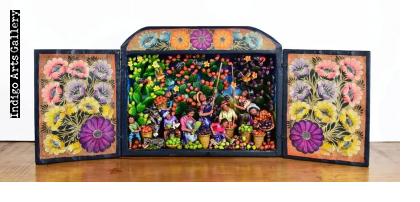

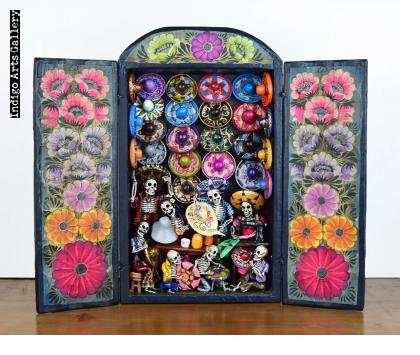

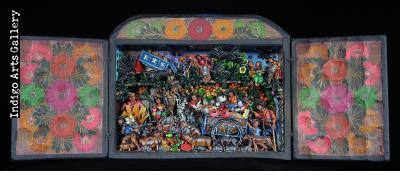

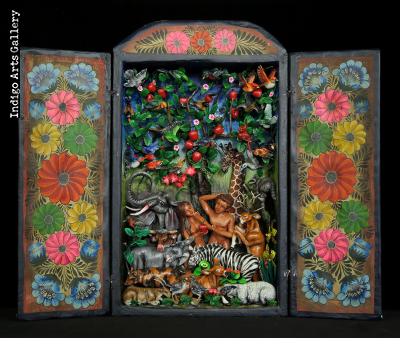

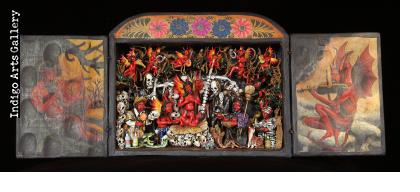

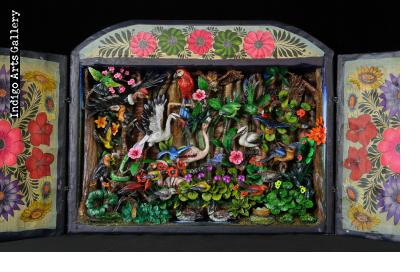

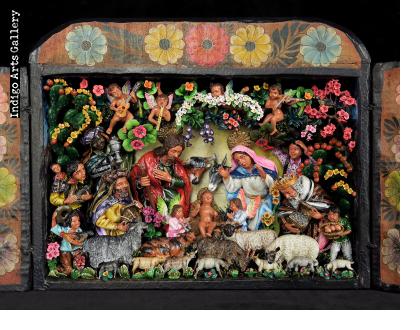

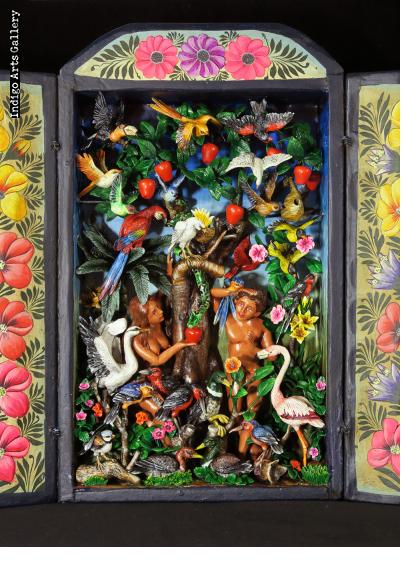

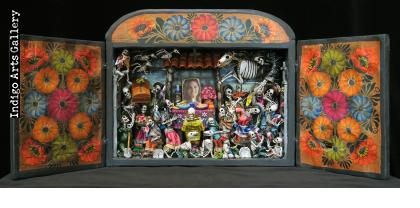

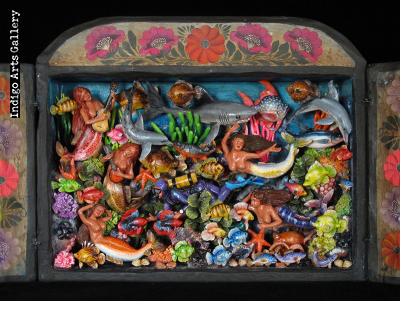

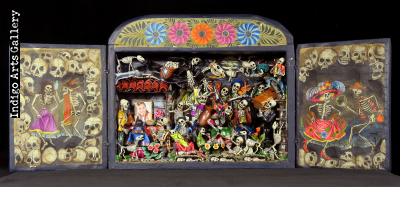

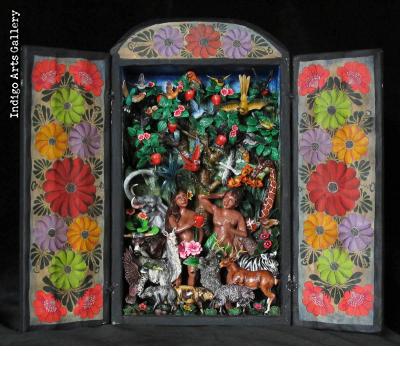

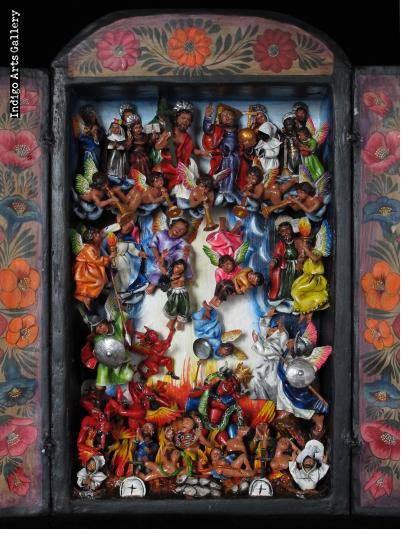

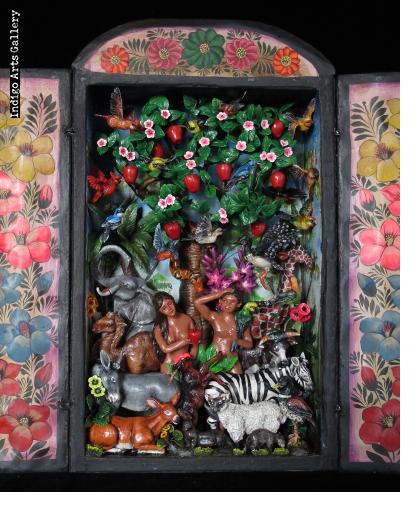

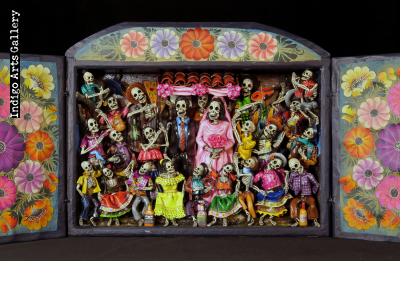

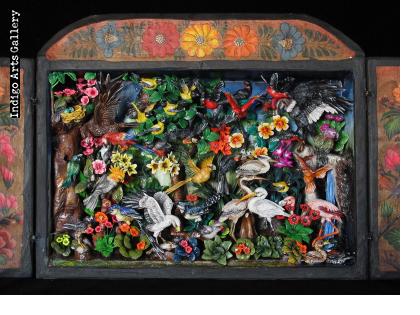

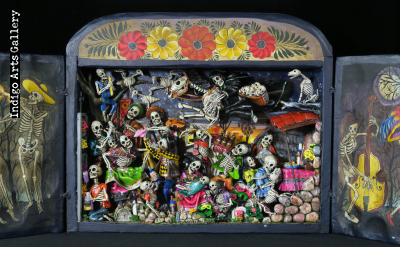

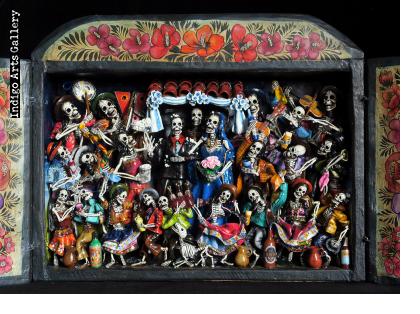

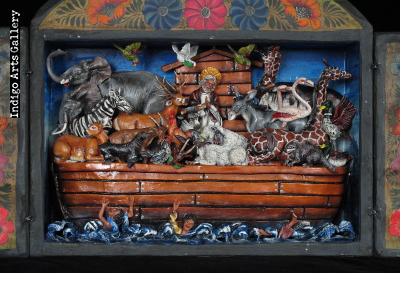

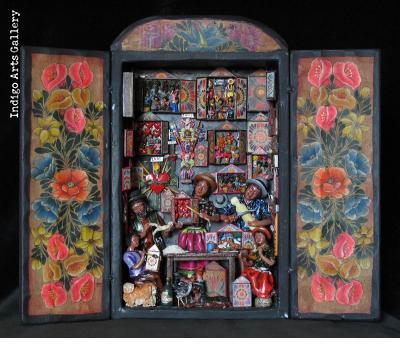

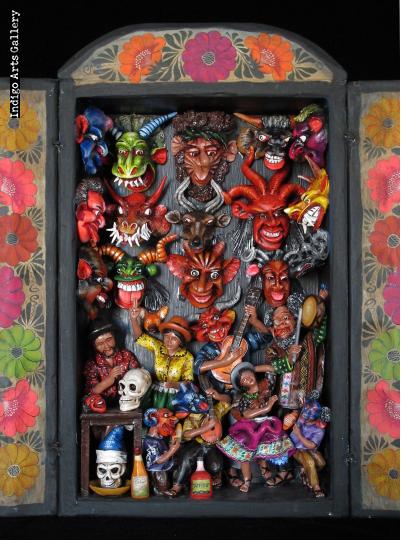

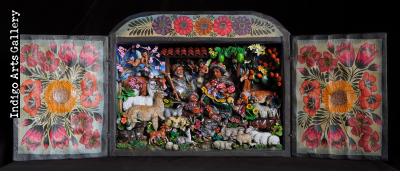

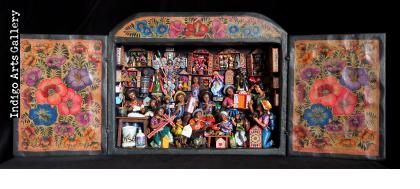

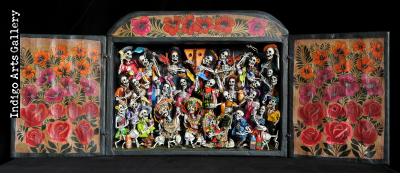

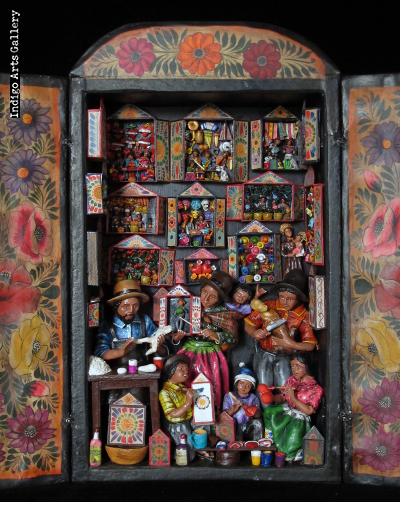

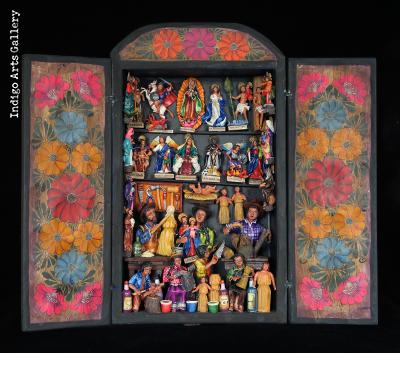

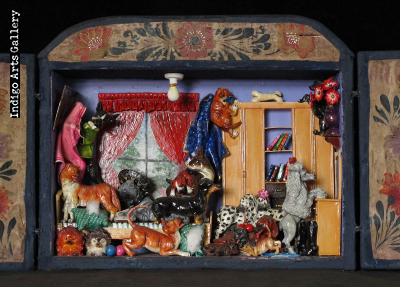

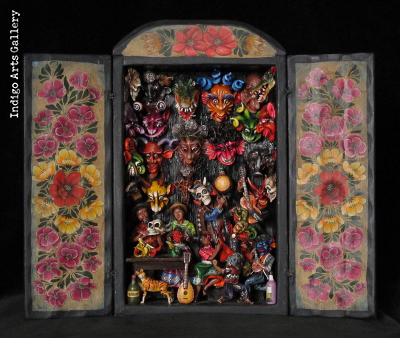

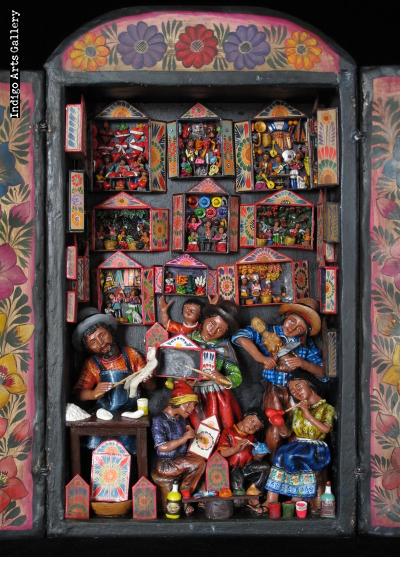

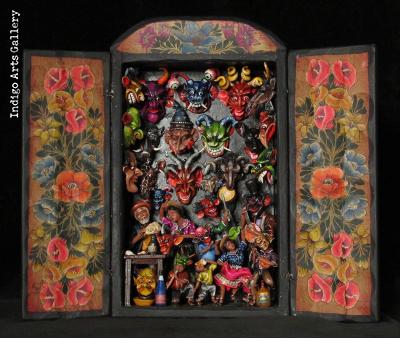

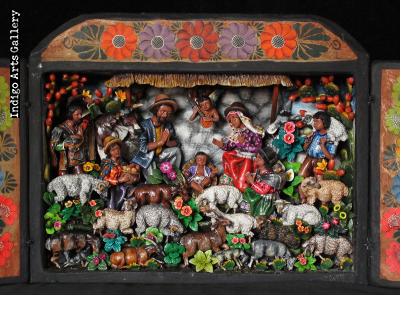

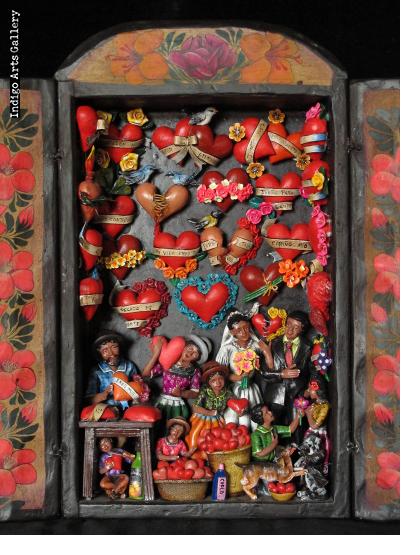

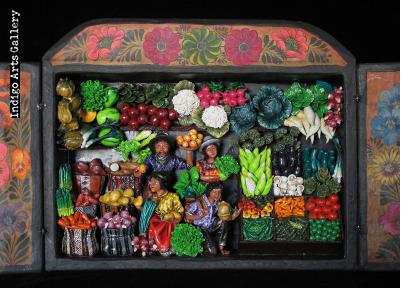

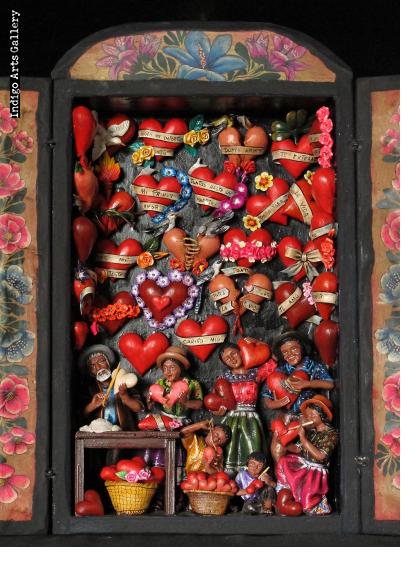

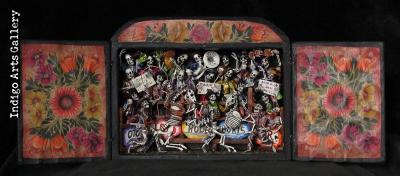

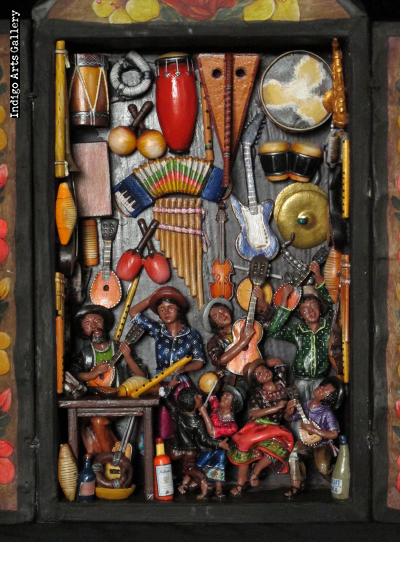

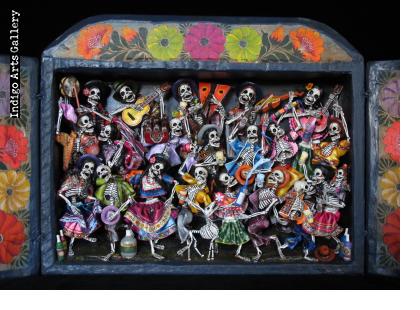

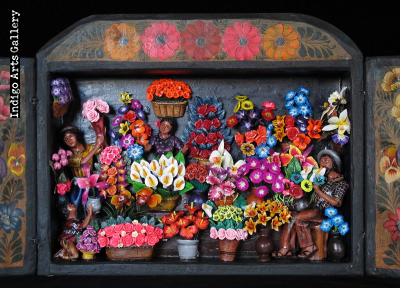

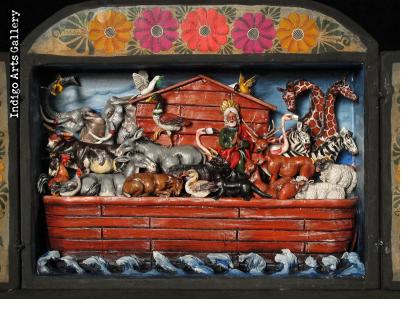

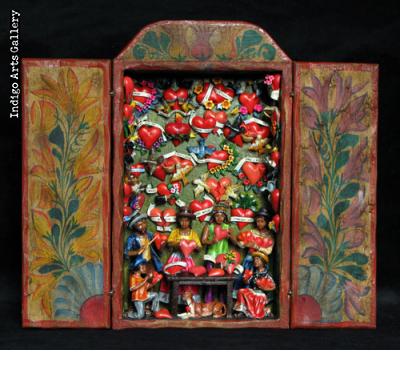

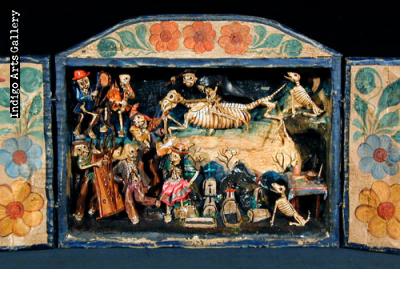

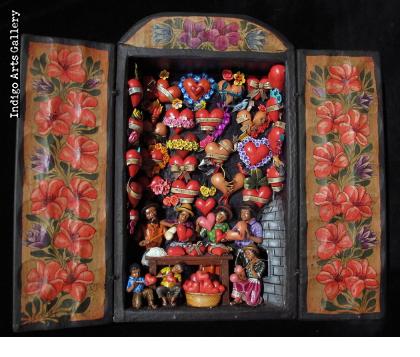

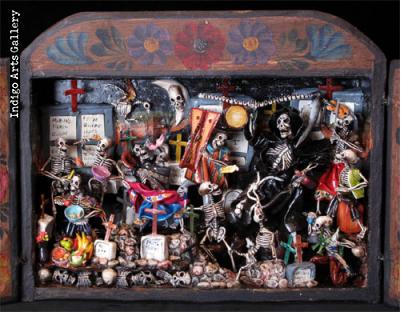

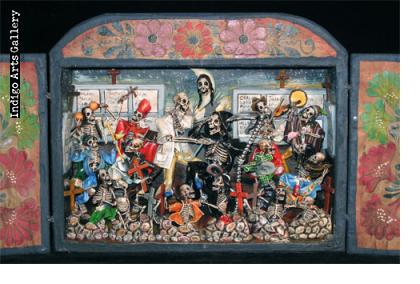

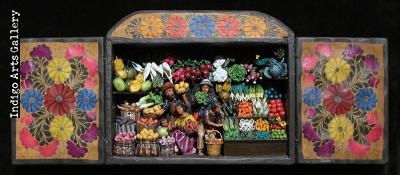

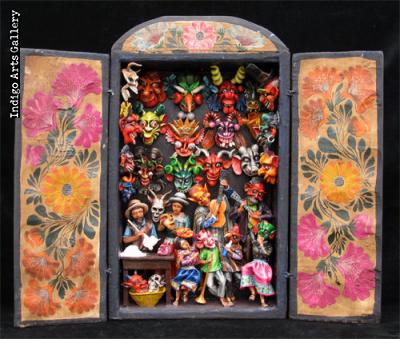

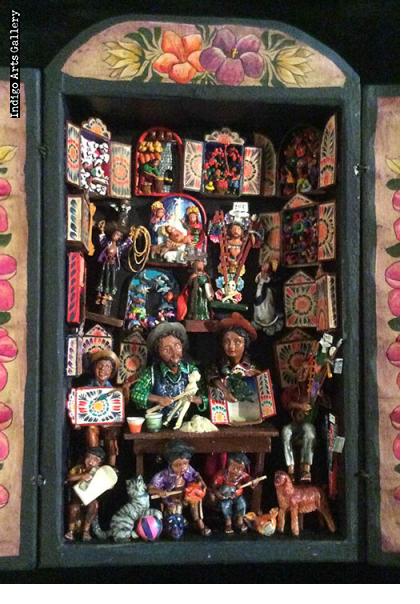

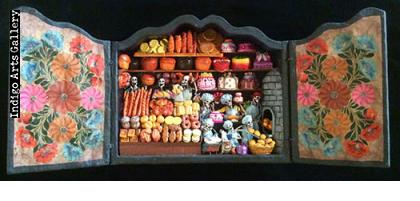

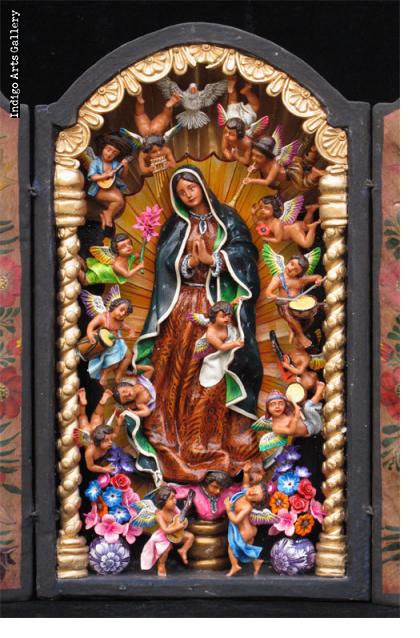

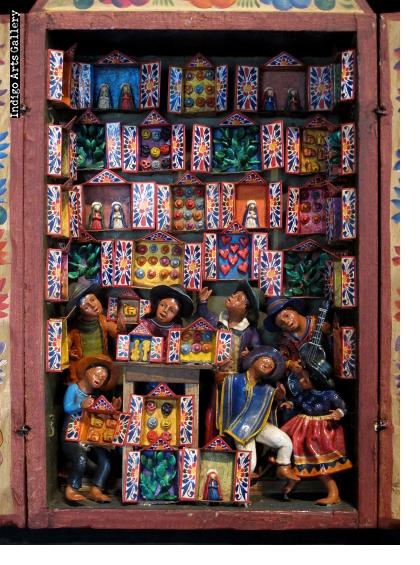

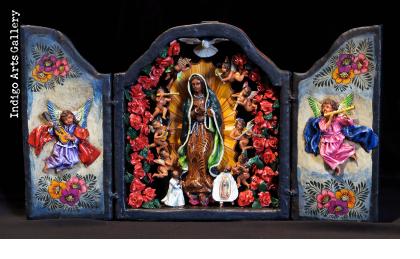

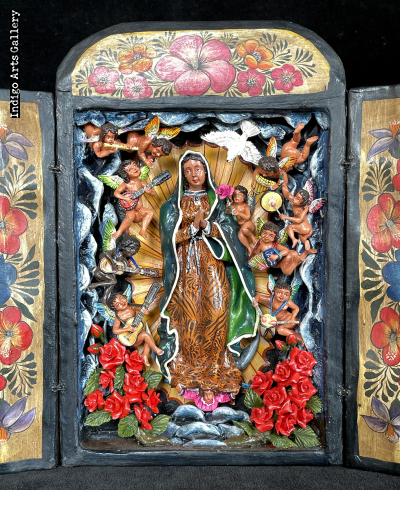

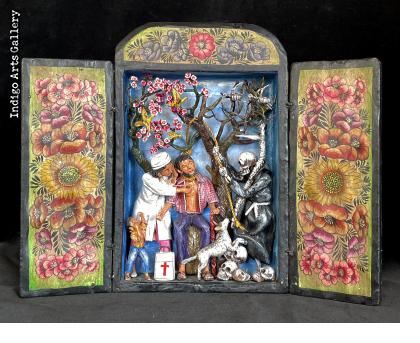

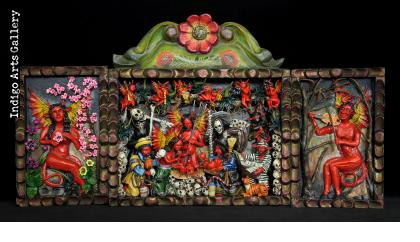

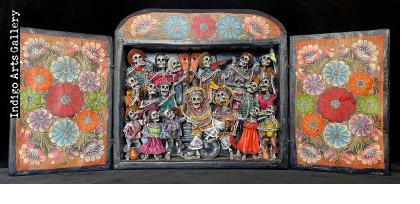

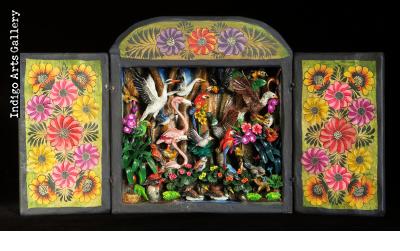

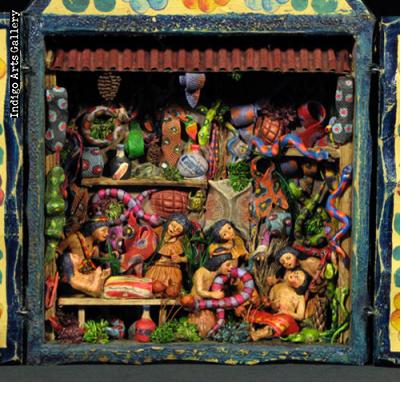

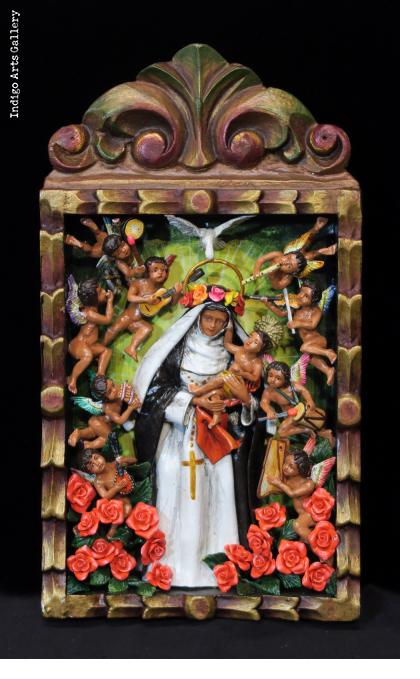

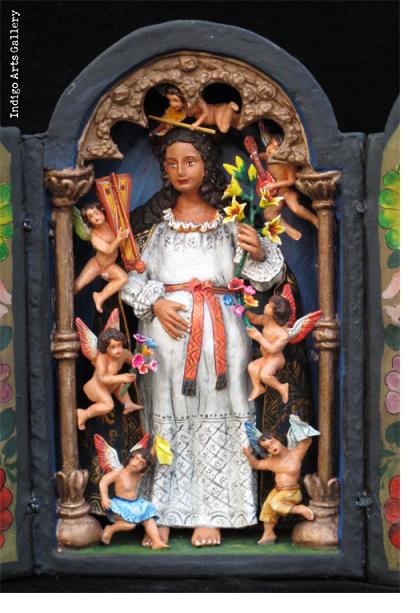

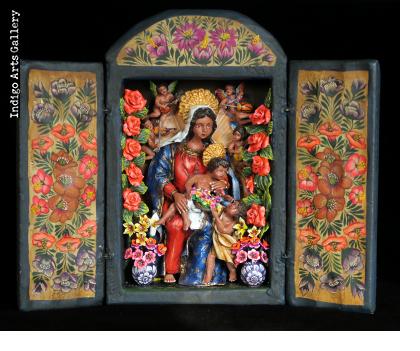

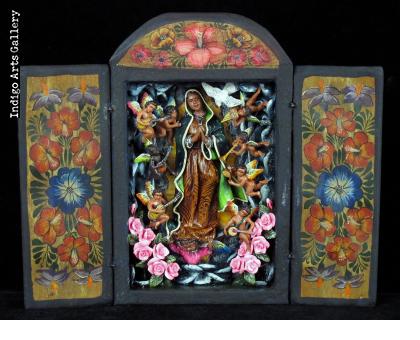

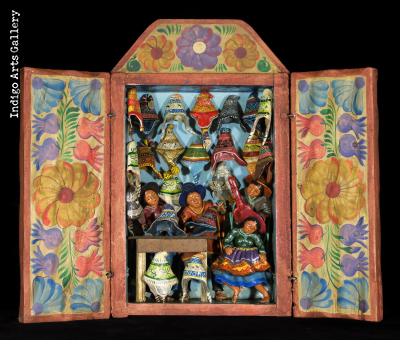

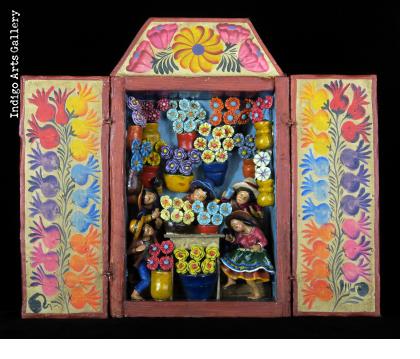

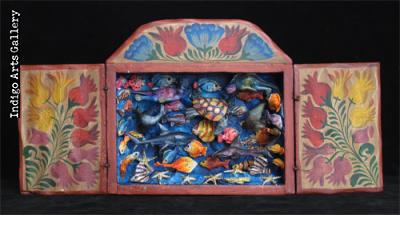

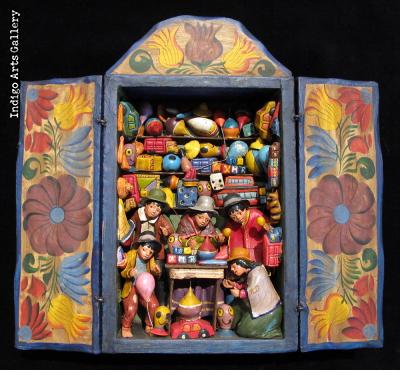

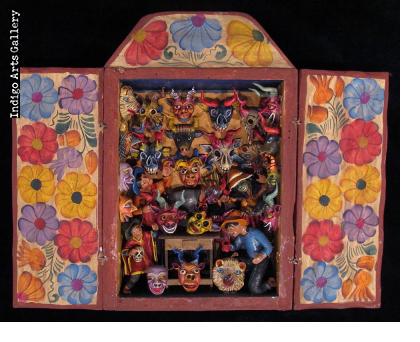

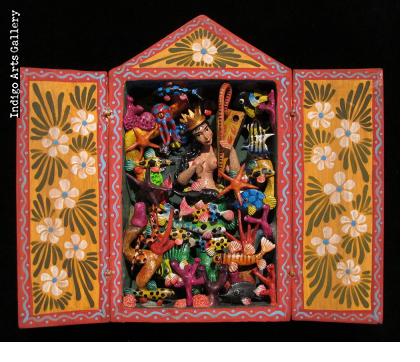

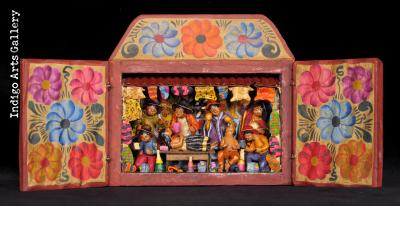

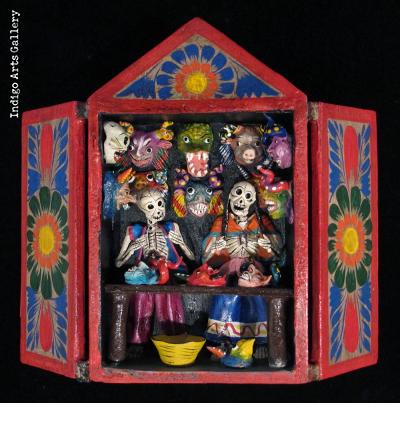

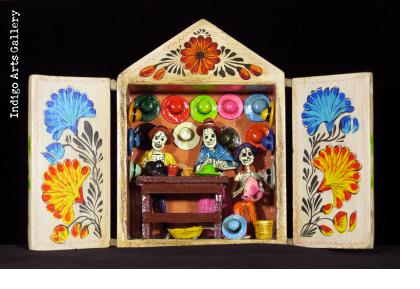

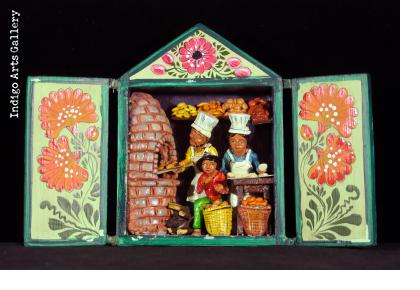

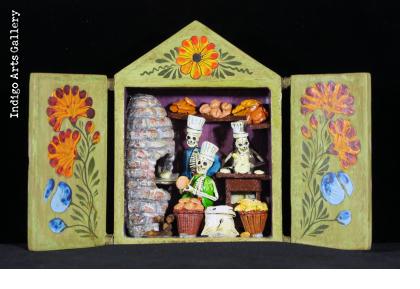

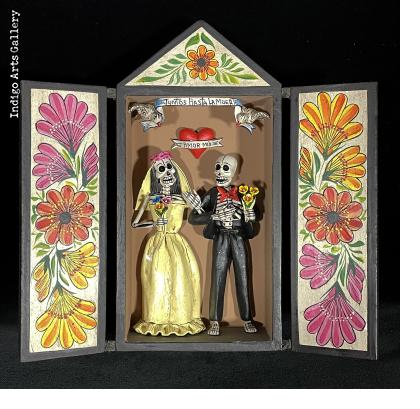

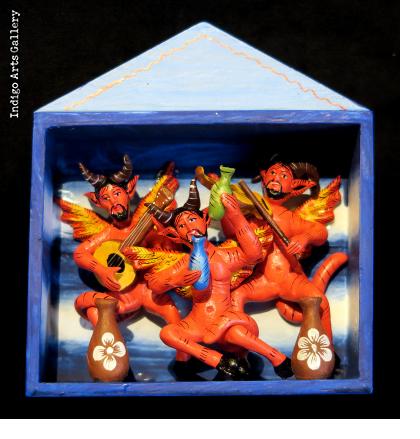

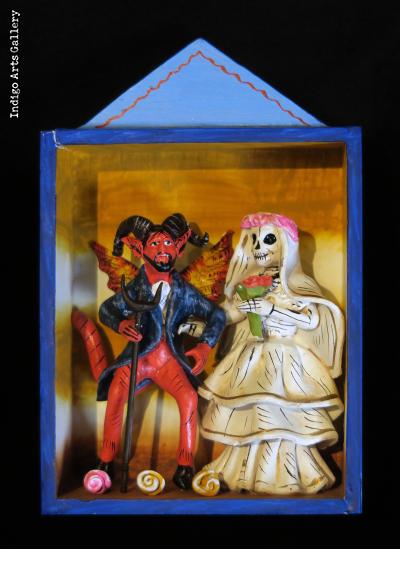

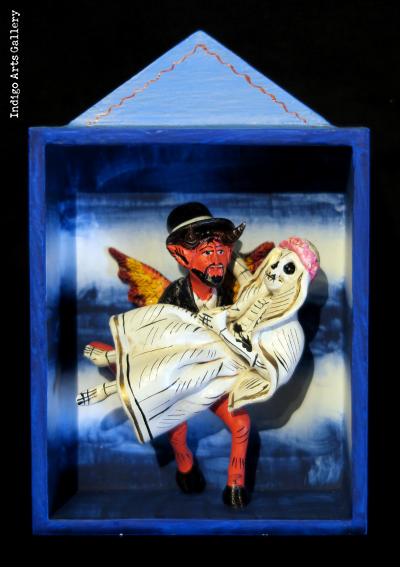

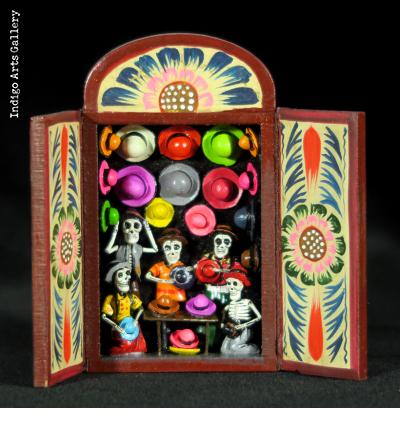

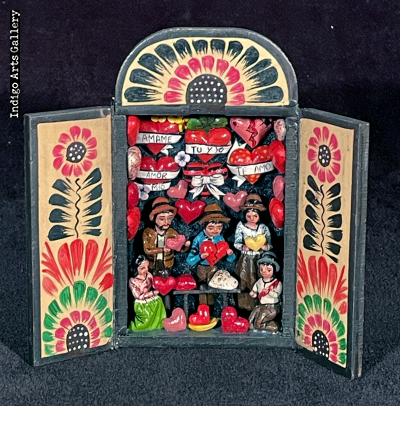

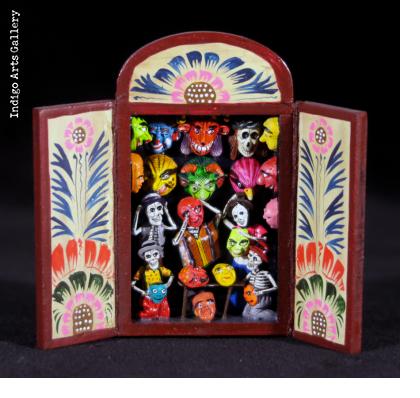

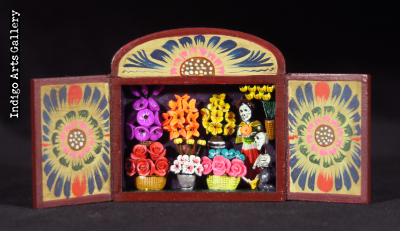

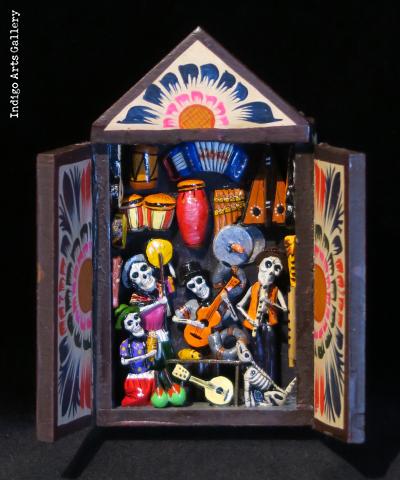

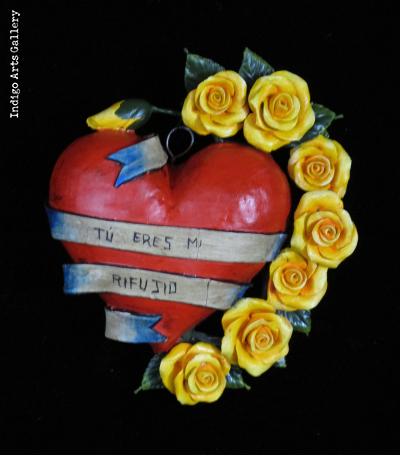

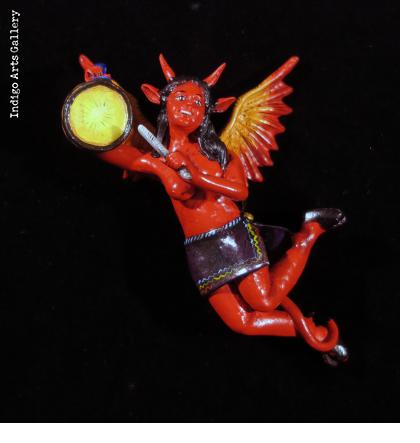

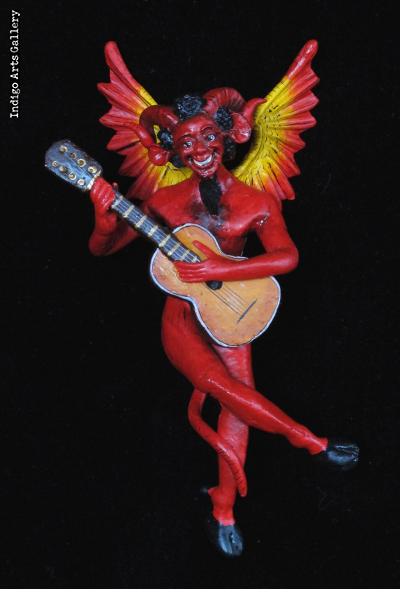

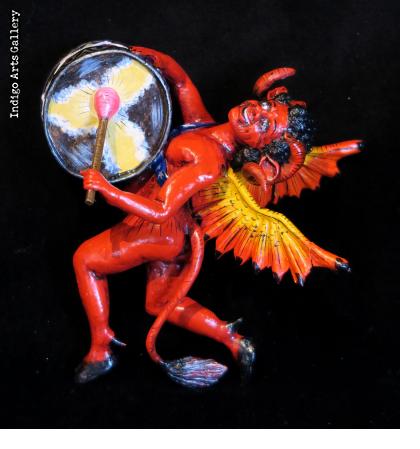

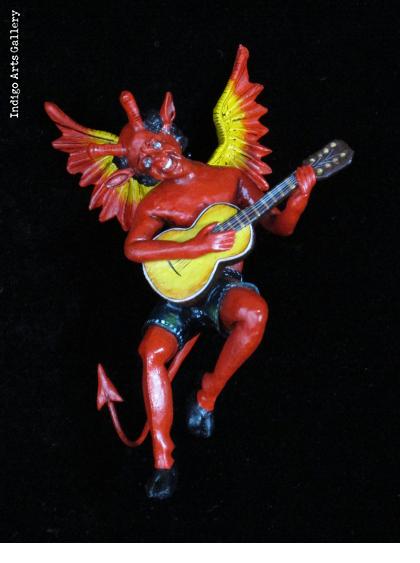

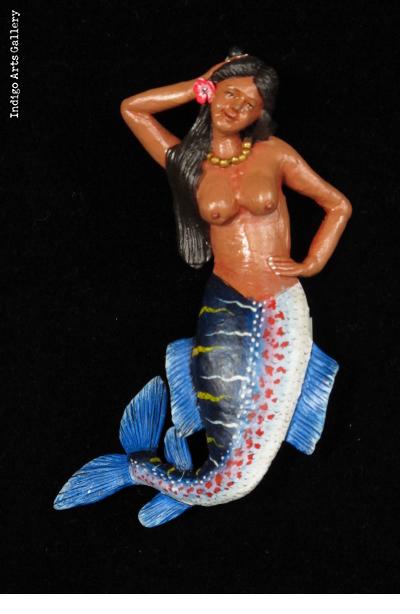

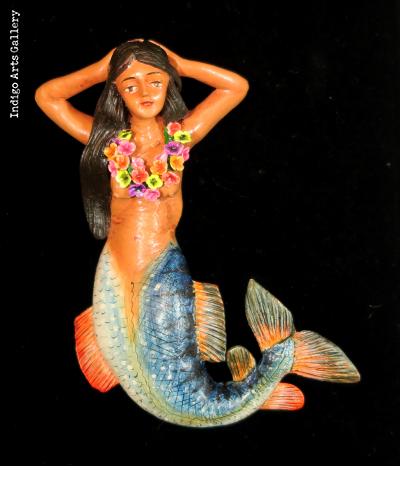

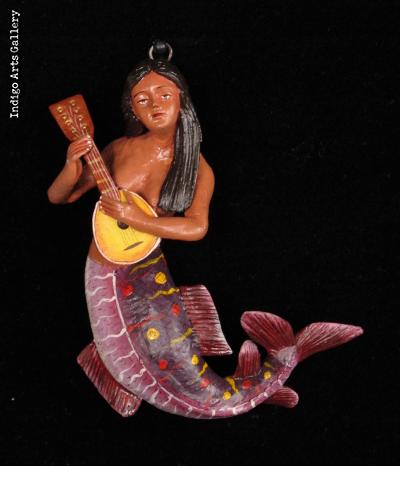

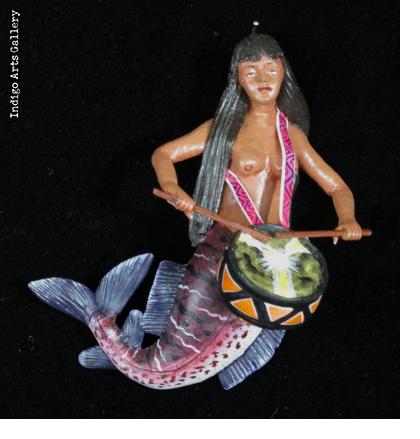

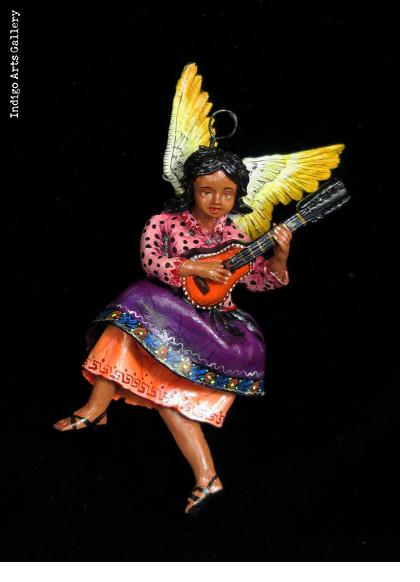

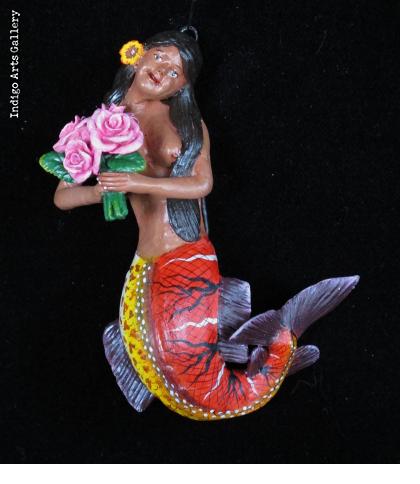

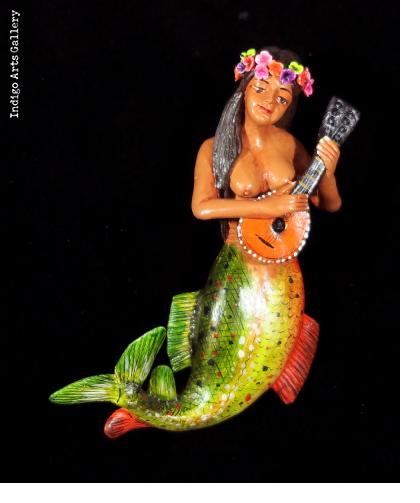

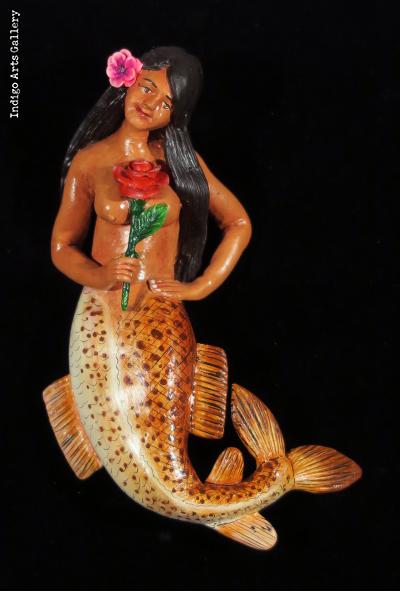

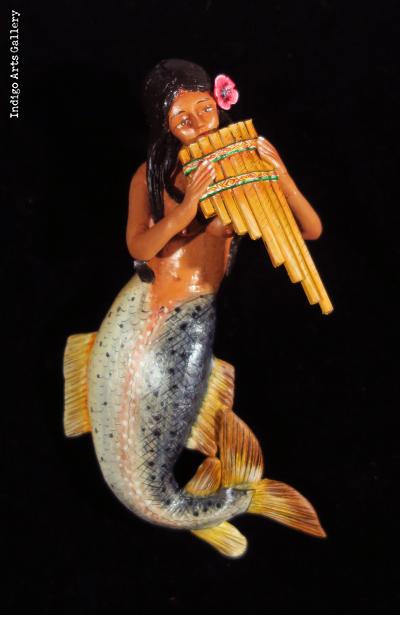

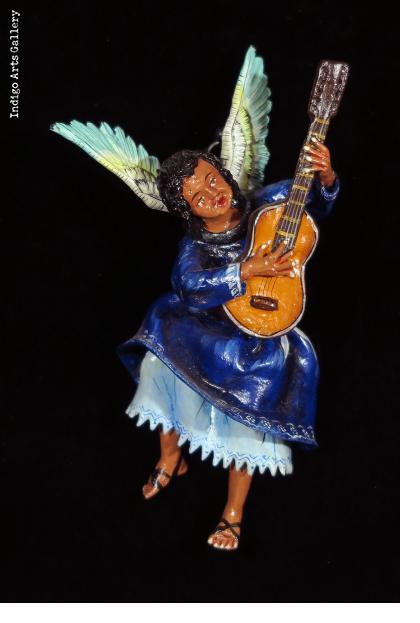

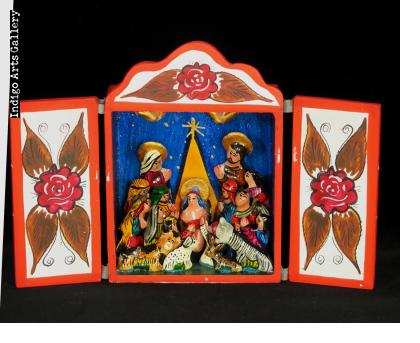

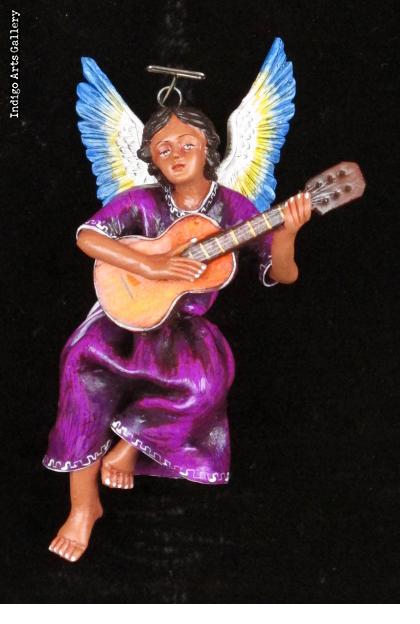

Shrines of Life celebrates the art of the contemporary Peruvian retablo. The retablo is a kind of portable shrine or nicho holding figures sculpted of pasta (a mixture of plaster and potato) or maguey cactus wood. The making of retablos is a folk art whose roots go back to the sixteenth century in the Andes (and even to the Greeks and Romans before that). While the art’s origins are religious, the contemporary Peruvian retablos exhibited at Indigo Arts range from the sacred to the secular, to the profane.

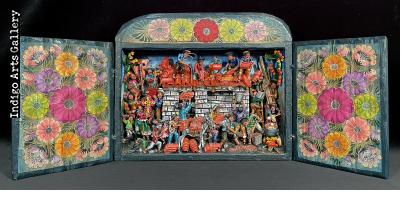

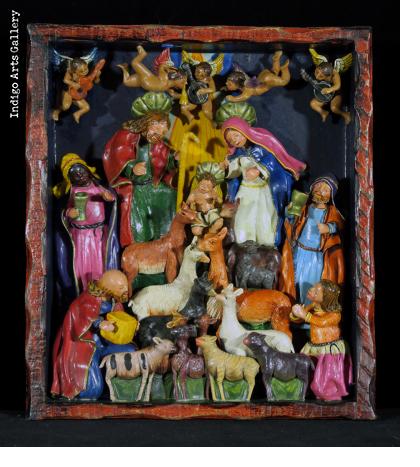

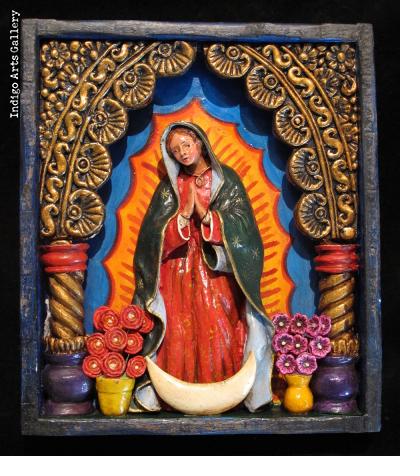

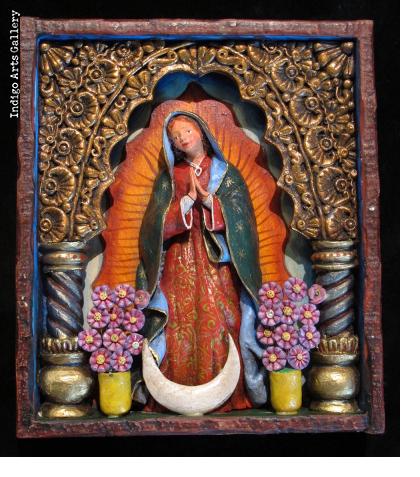

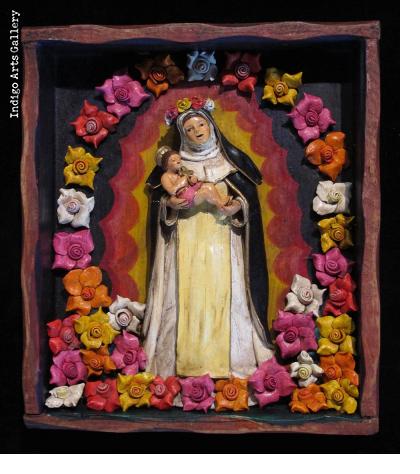

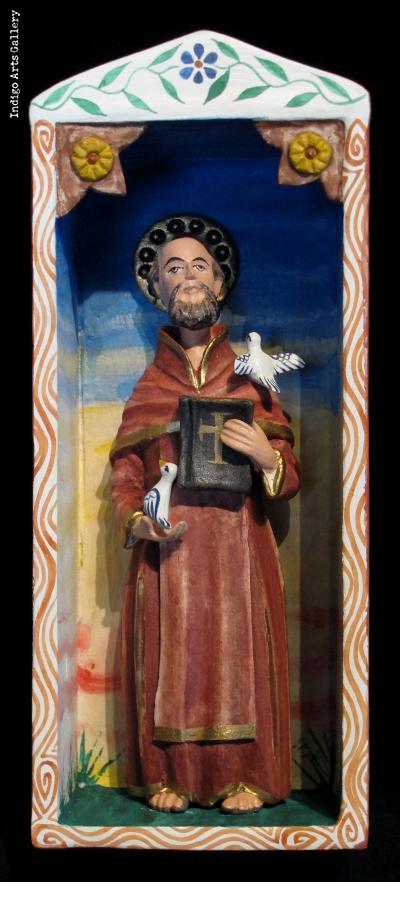

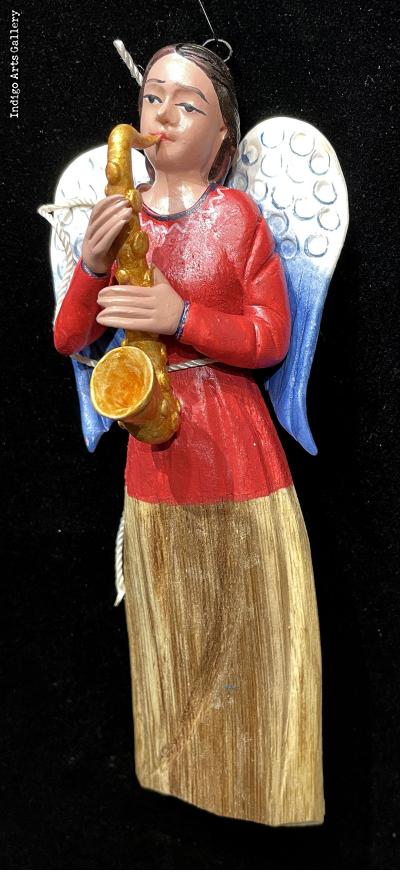

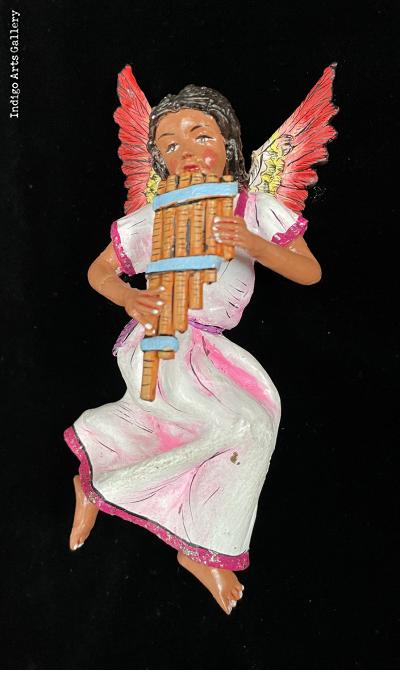

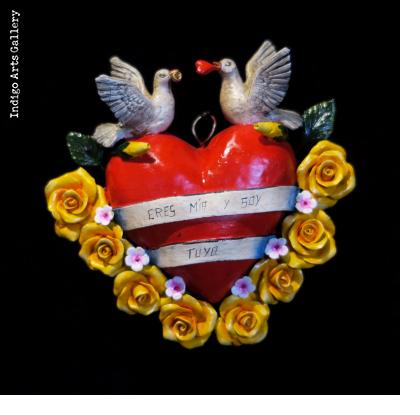

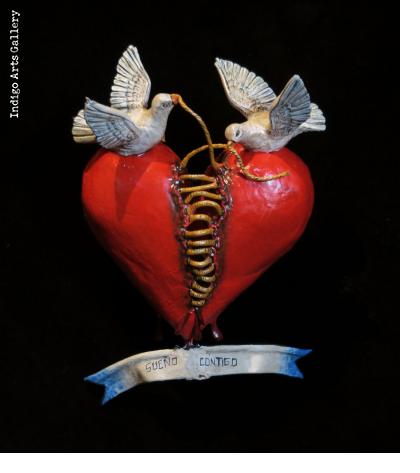

Spanish priests and colonists introduced small portable shrines in the 16th century to aid in the conversion and instruction of the Indian population of the Andes. These were generally wooden boxes like miniature houses, holding images of saints carved of stone or maguey cactus wood or molded of pasta - a mix of plaster with potato. Known as cajas de imaginero, these portable shrines could be placed in the home for private worship, displayed in festivals, or carried from village to village by missionaries, travelers and the mule-train drivers known as arrieros.

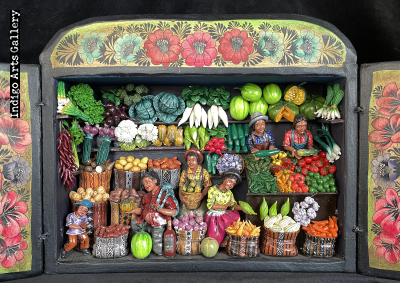

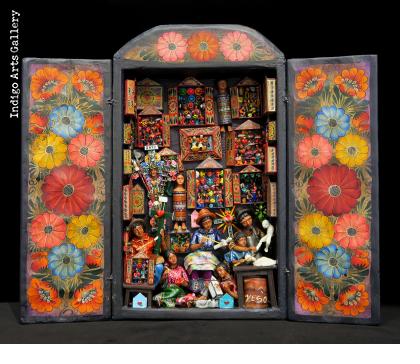

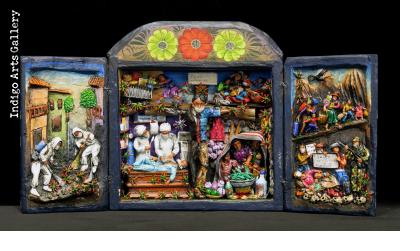

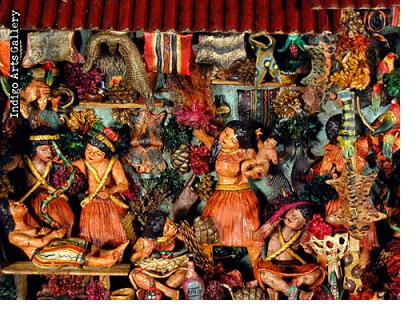

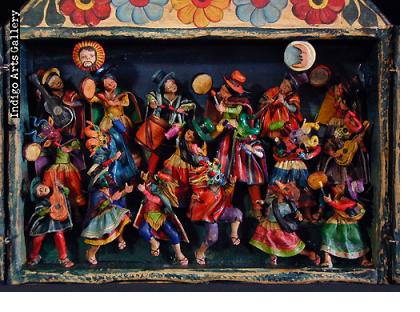

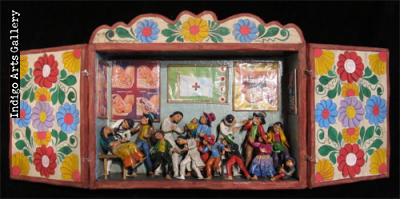

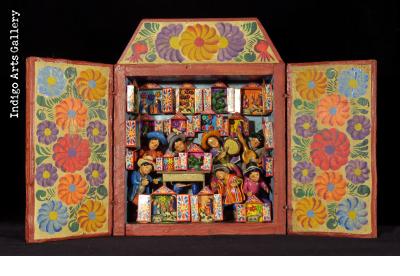

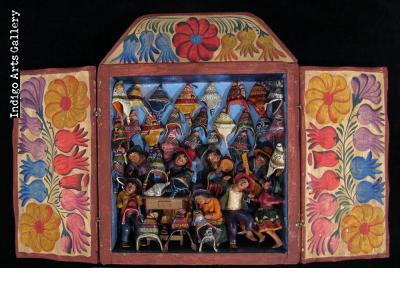

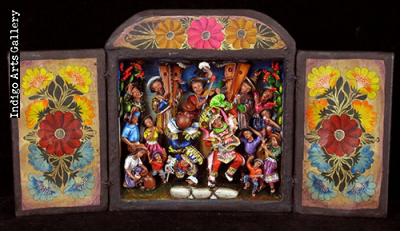

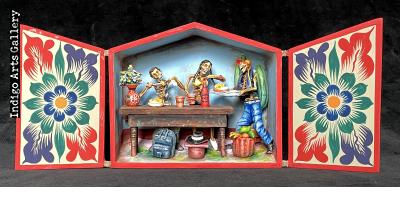

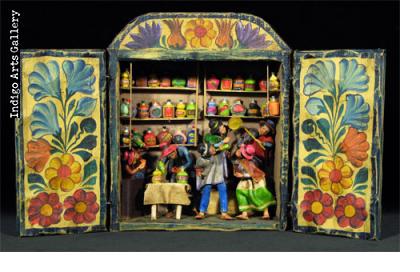

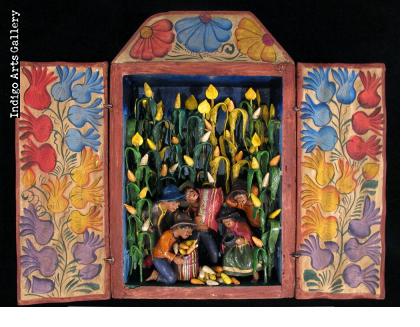

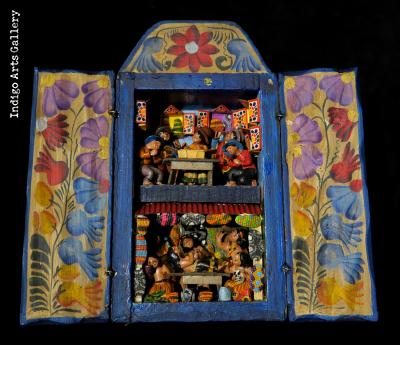

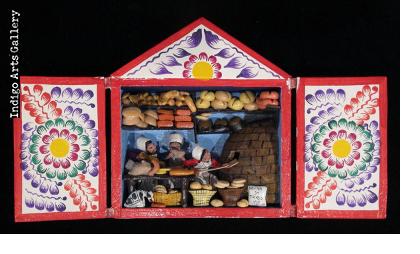

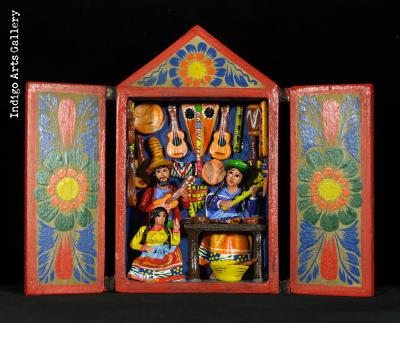

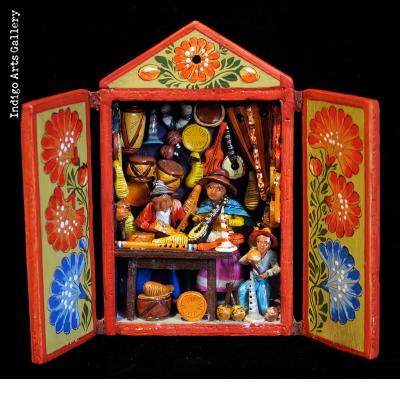

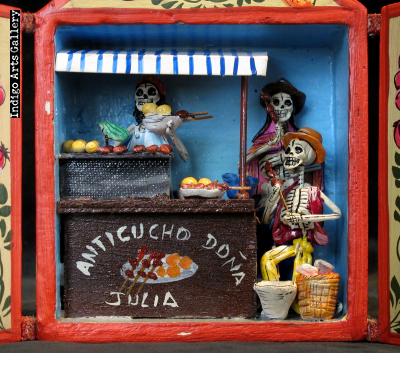

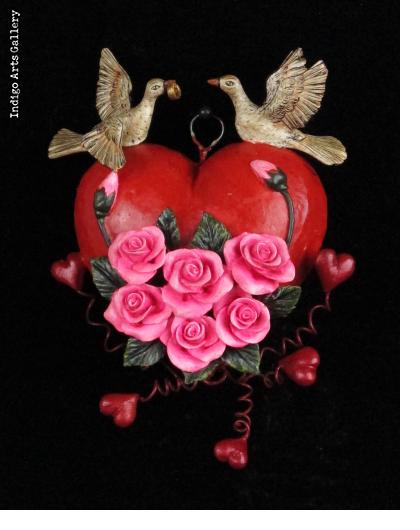

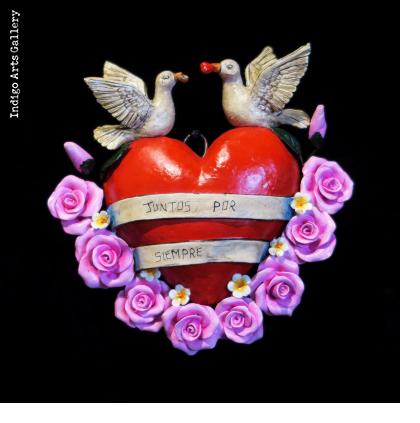

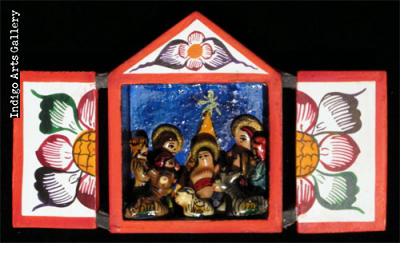

Over the coming centuries distinct variations evolved in the isolated Andean regions of Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru. By the mid-20th century, as construction of new roads and railroads changed trade and travel routes, the folk art had begun to change and in some areas even die out. It became common to pair secular scenes with the images of the saints. Two-level retablos, like two-storey houses, might have a scene of the nativity above, and a story of peasant life below. Popular scenes in the Huamanga region of Peru were the pasion, which depicted the punishment of a thief by a hacienda owner, or the reunion, which depicted various occupations and activities of rural life.

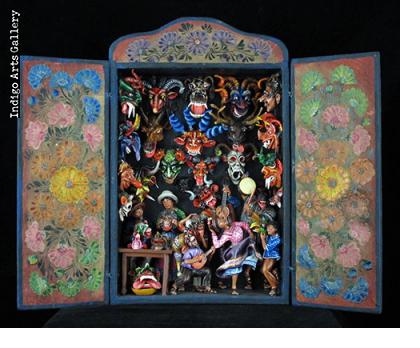

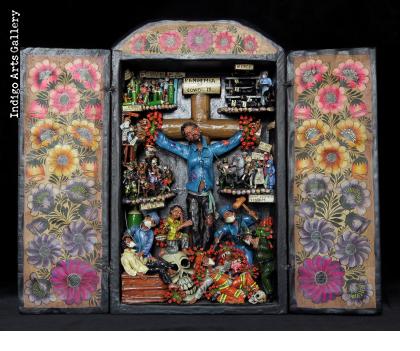

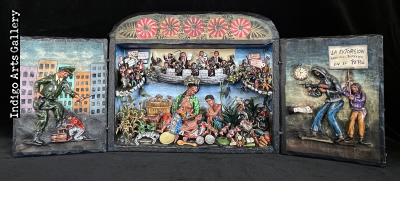

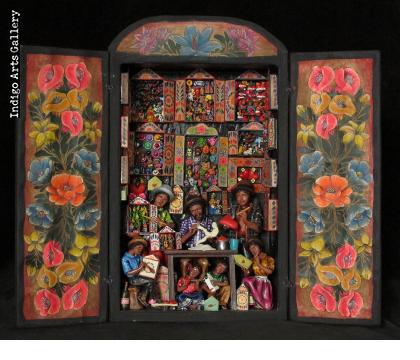

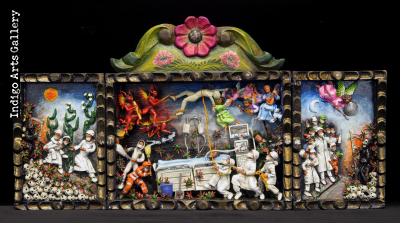

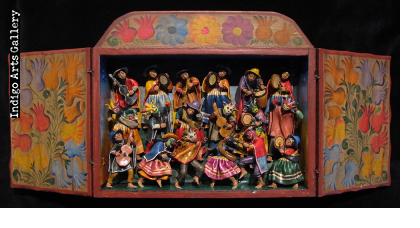

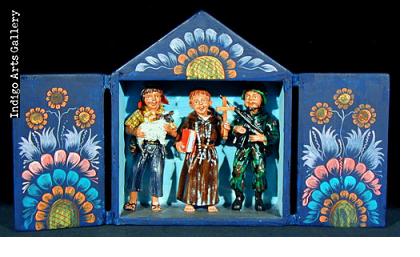

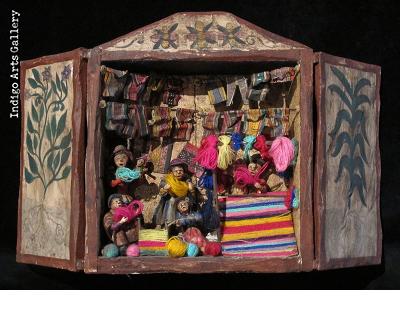

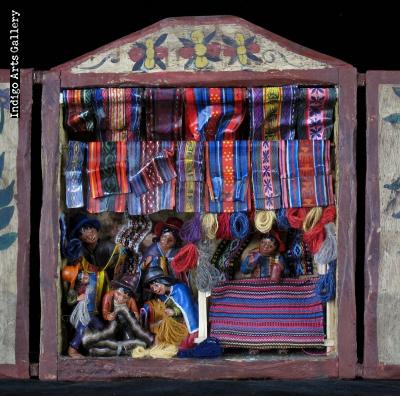

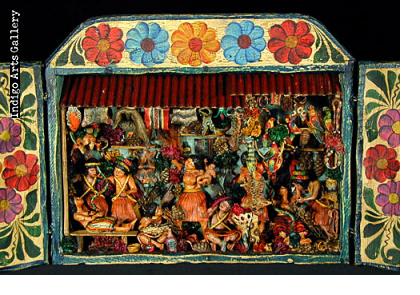

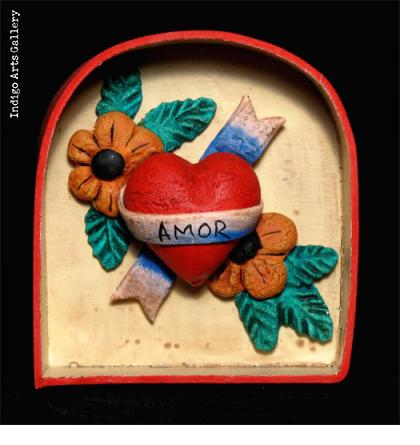

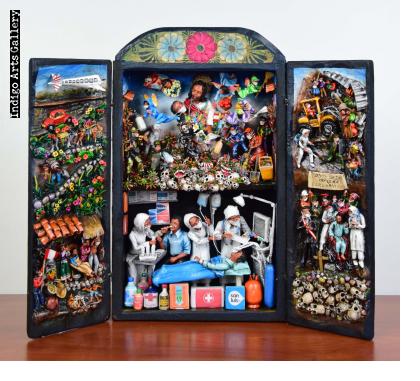

Beginning in the 1940s an indigenista movement among Peruvian intellectuals brought attempts to encourage (but inevitably change) traditional Andean crafts. To broaden the appeal of the shrines to collectors they encouraged the artists to depict festivals and rural pastimes, as well as events of Peruvian history. These more secular shrines came to be called retablos, a term derived from the Latin res tabula, the screen behind the altar in a church, which was commonly applied to small paintings of the saints in Mexico and Guatemala. The term stuck and the interest in retablos as an art form grew. Another key event in the development of the retablo was the brutal civil war of the 1980’s and early 1990’s, which pitted a violent revolutionary group, the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) against equally ruthless government forces. The peasants caught in the middle suffered the deaths or disappearances of some 70,000 people in this period.

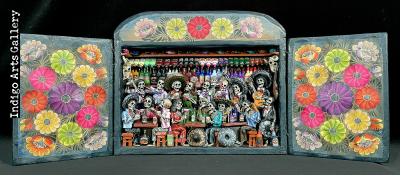

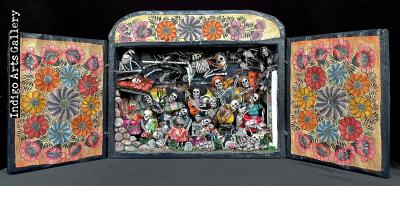

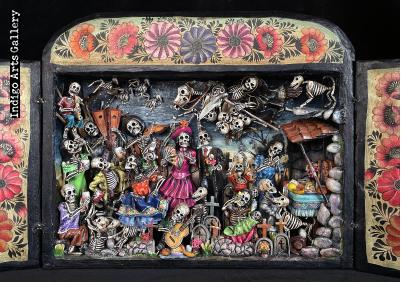

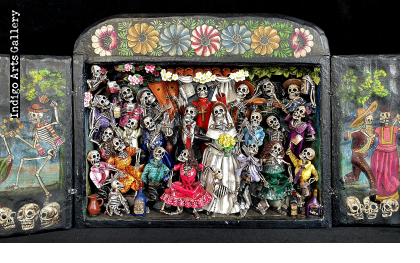

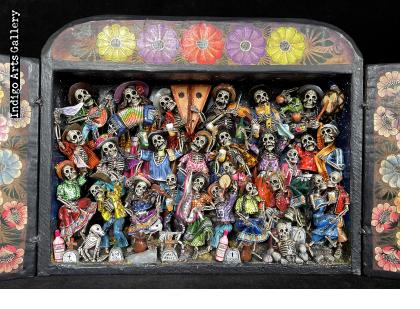

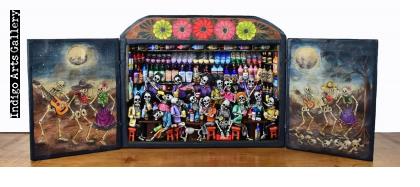

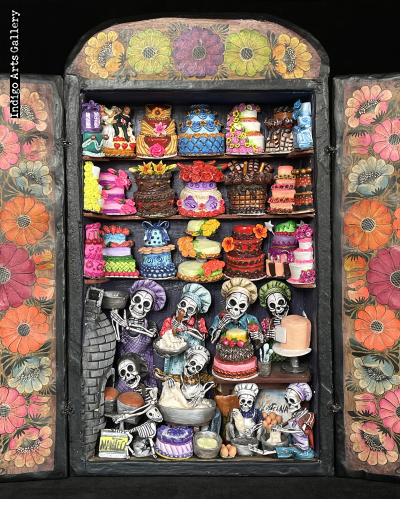

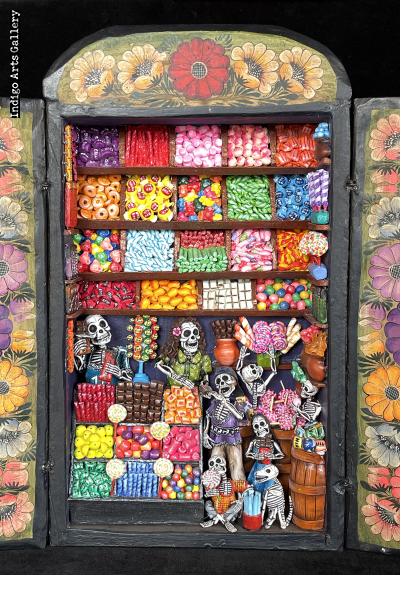

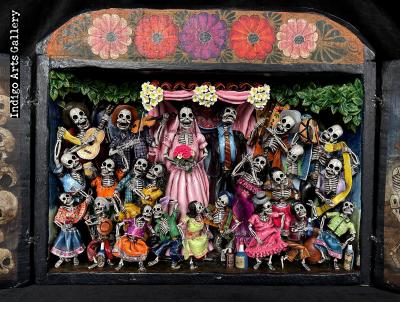

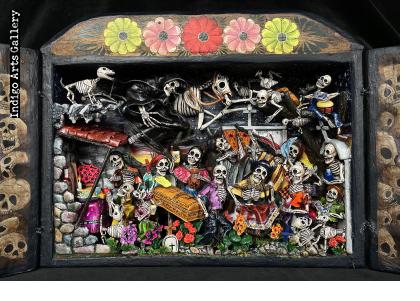

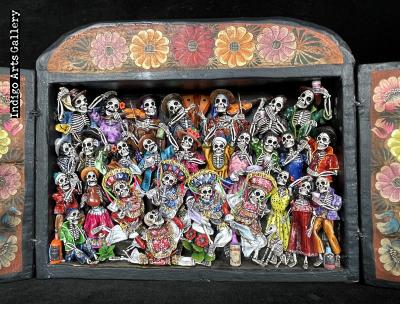

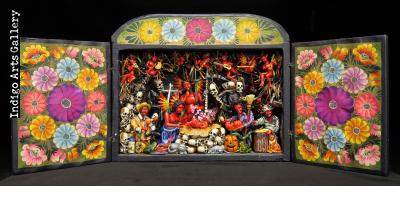

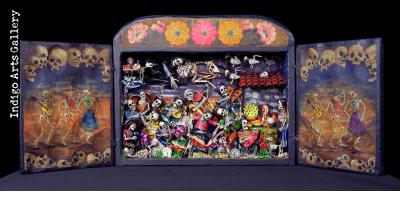

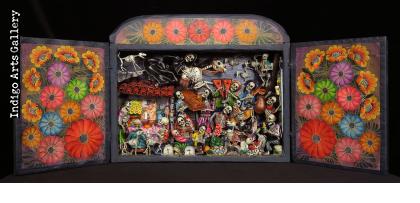

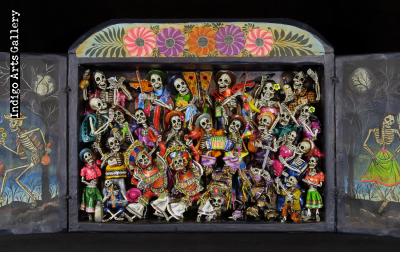

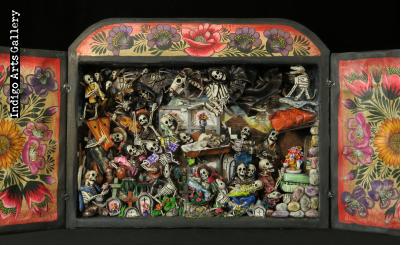

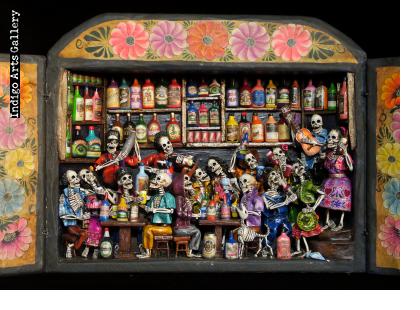

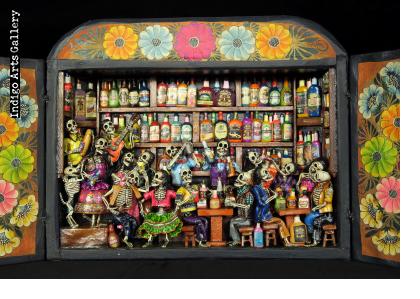

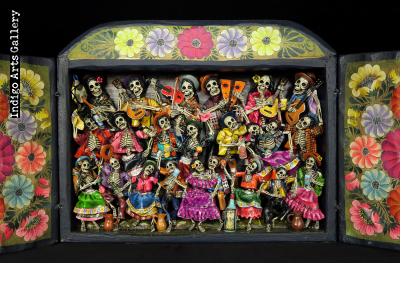

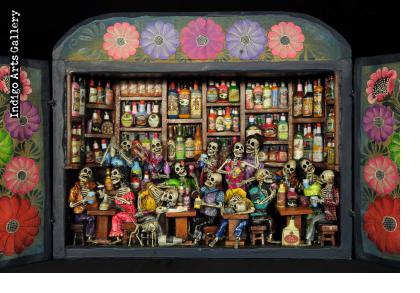

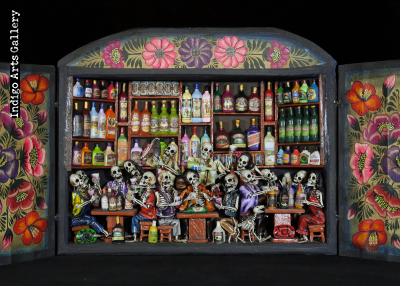

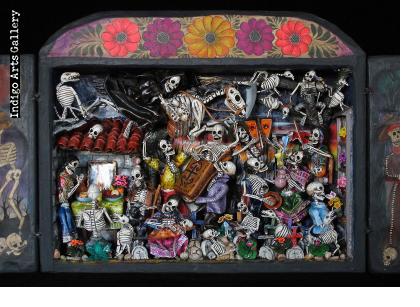

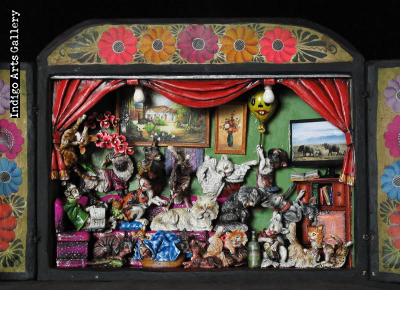

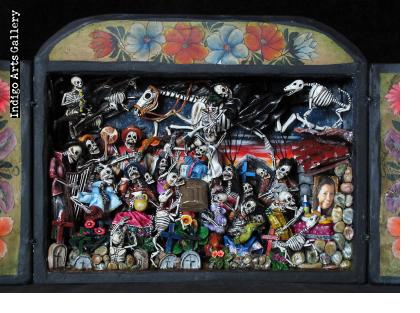

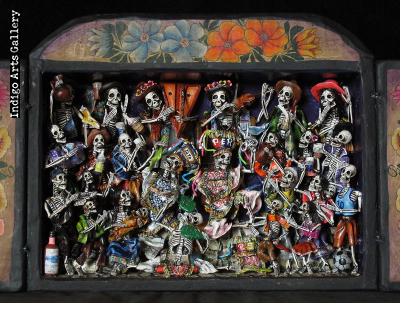

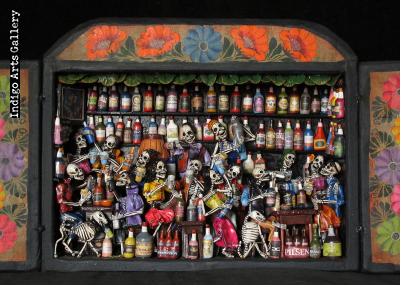

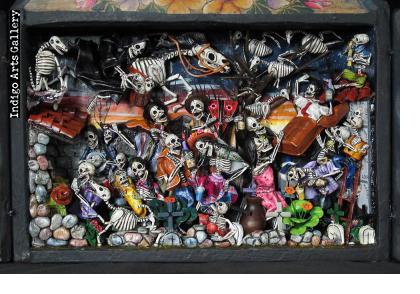

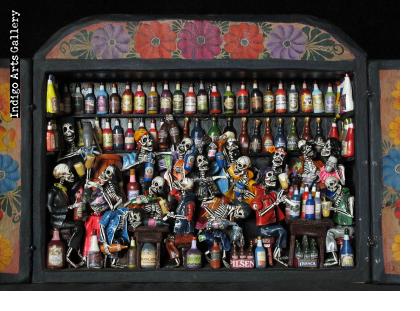

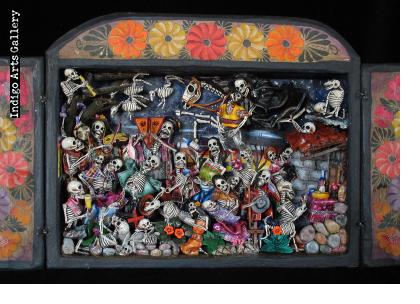

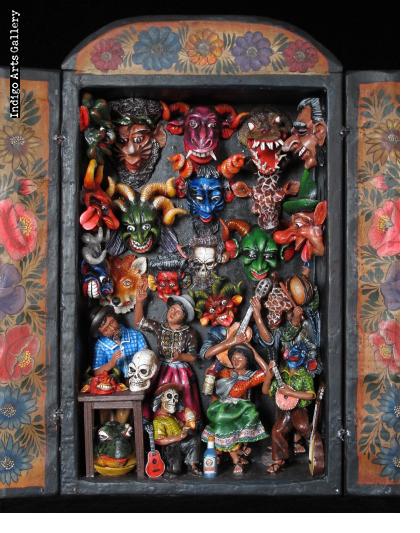

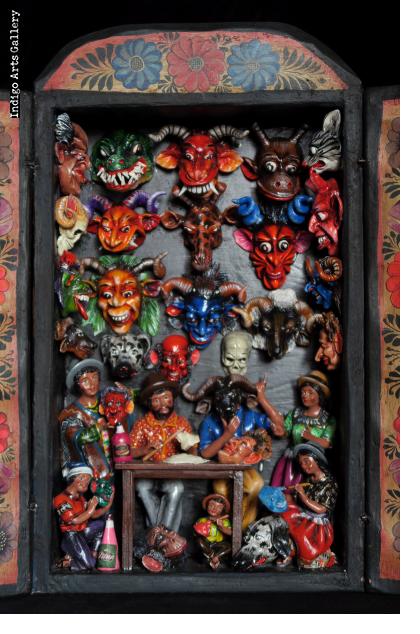

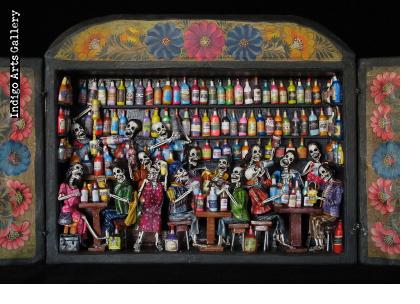

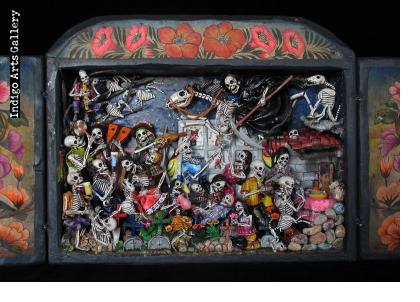

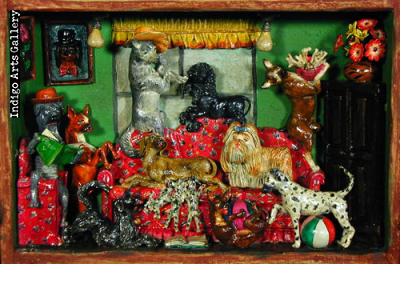

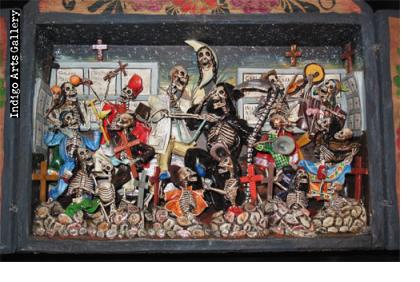

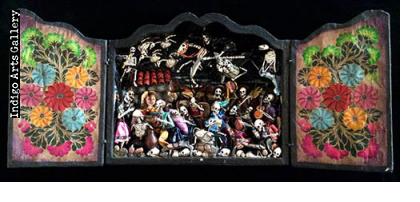

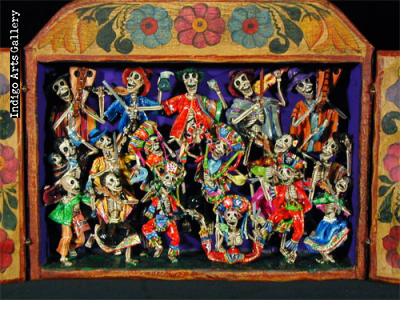

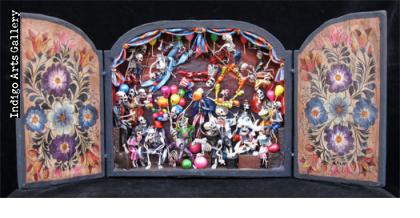

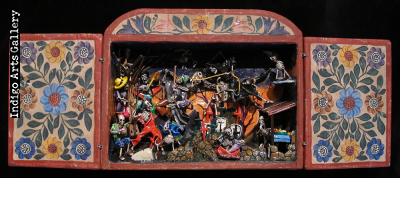

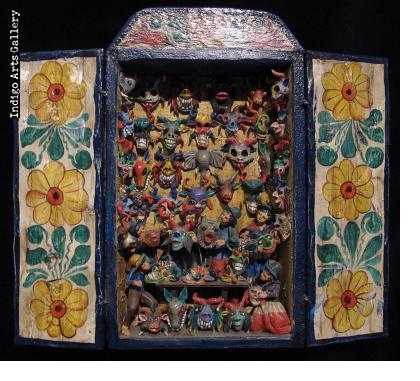

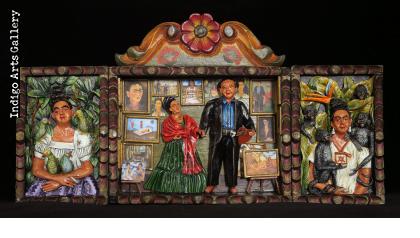

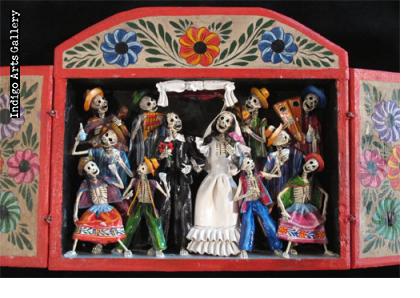

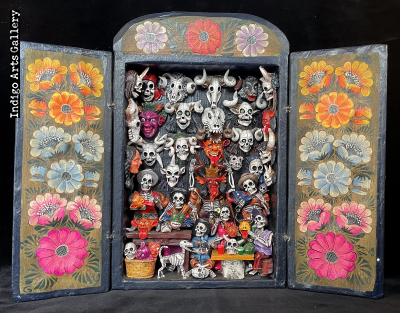

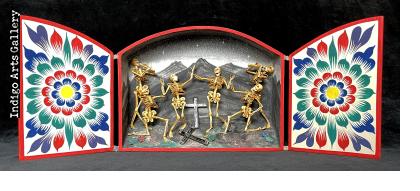

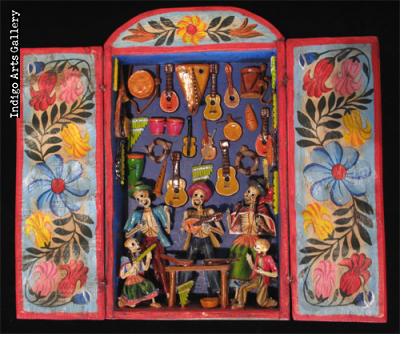

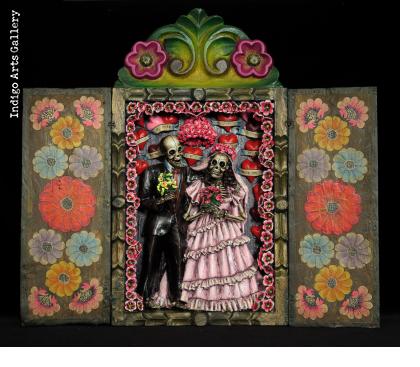

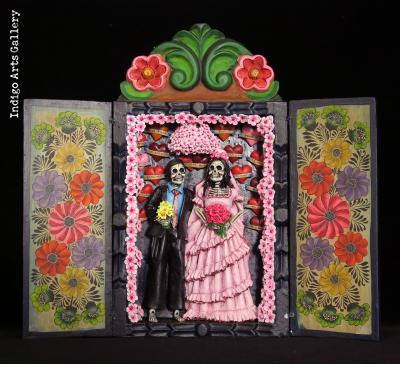

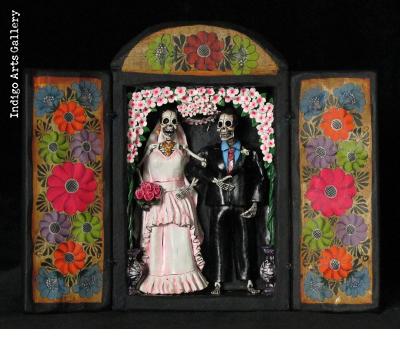

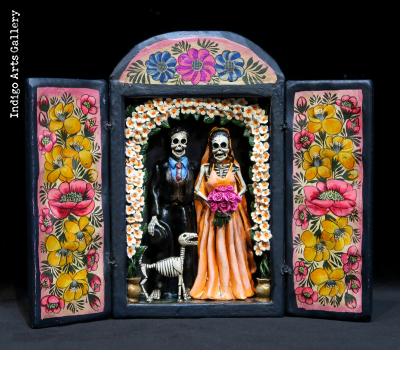

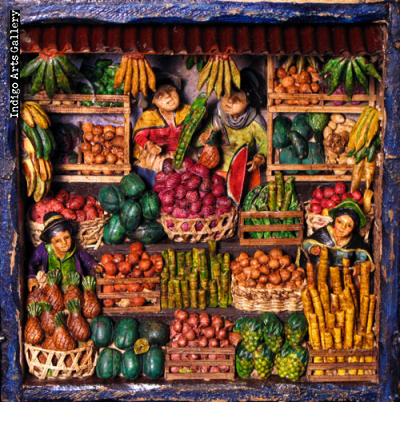

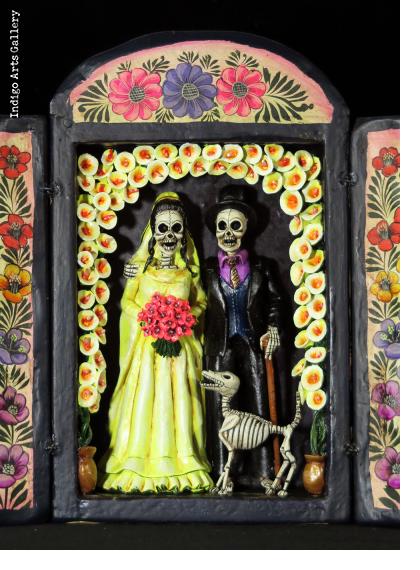

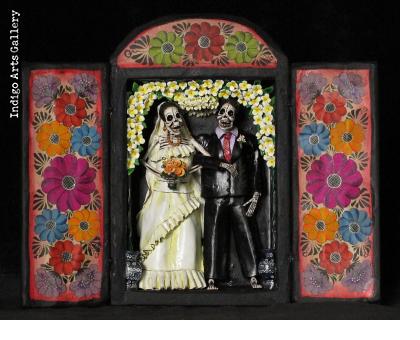

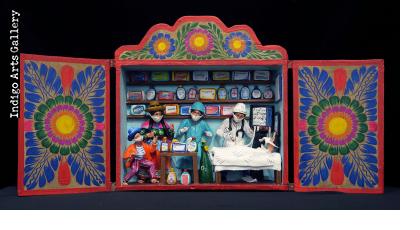

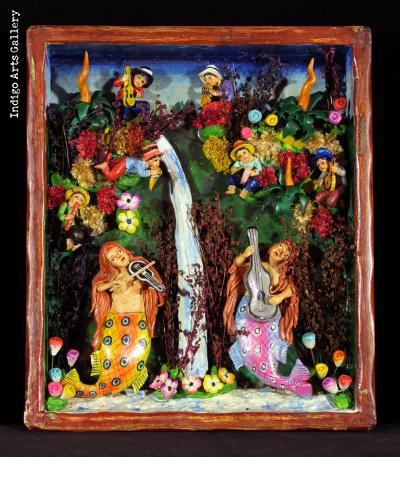

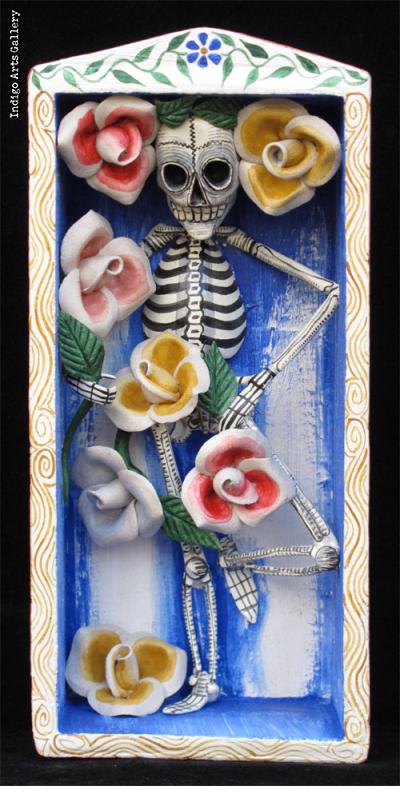

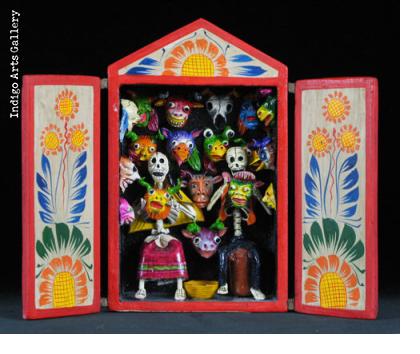

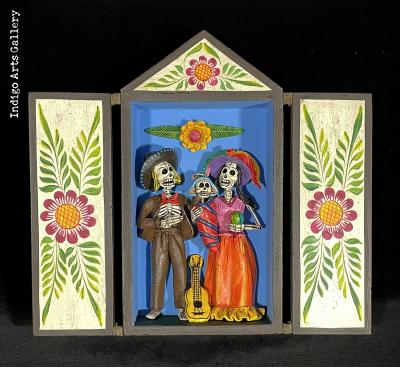

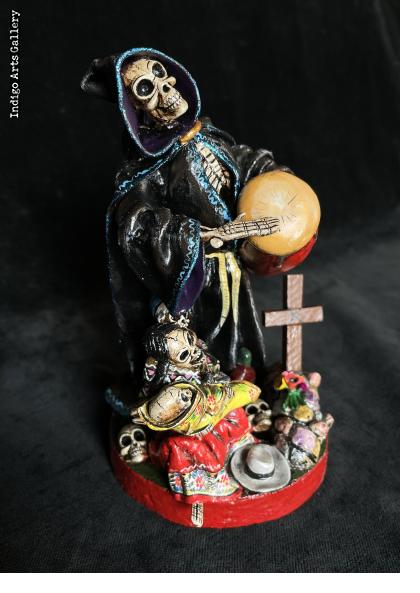

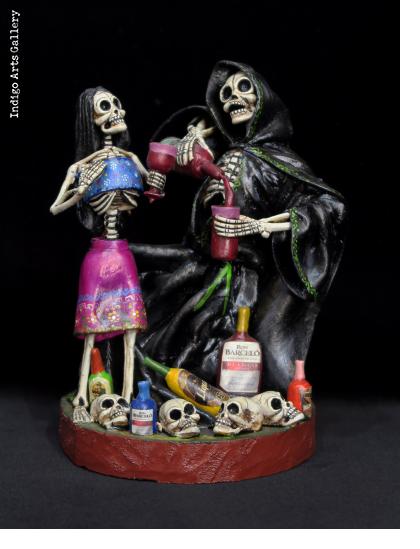

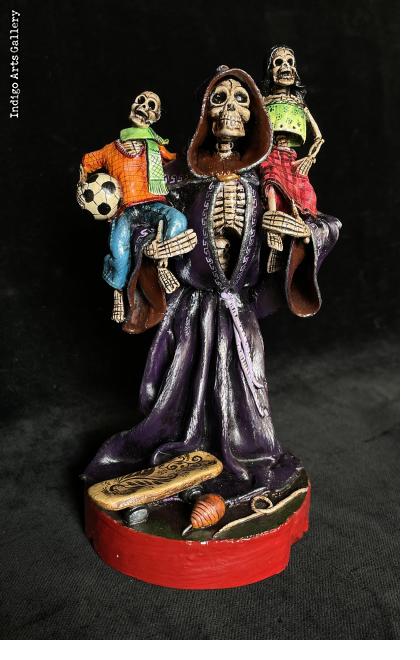

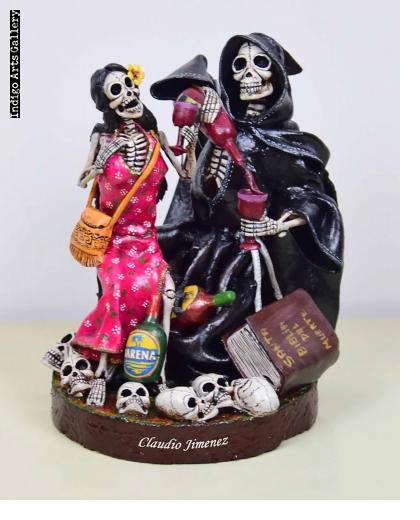

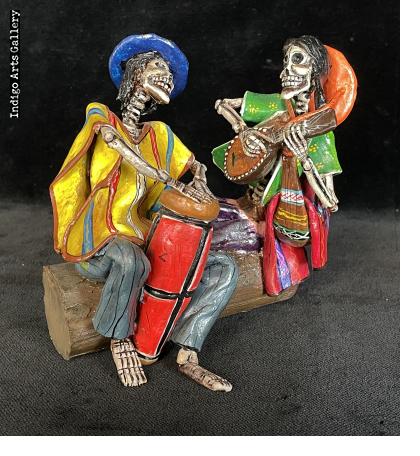

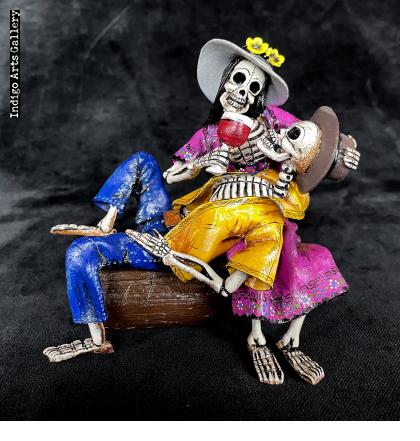

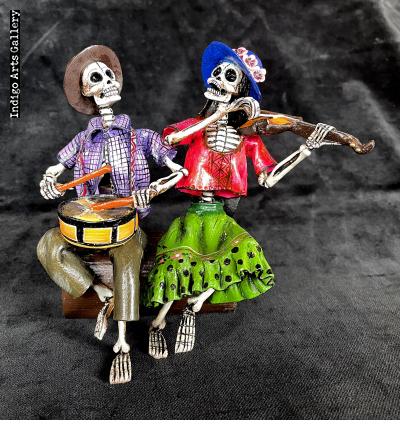

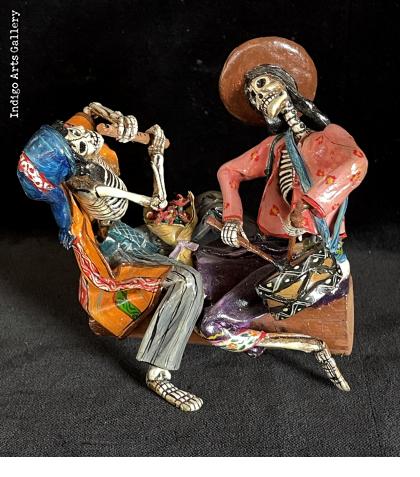

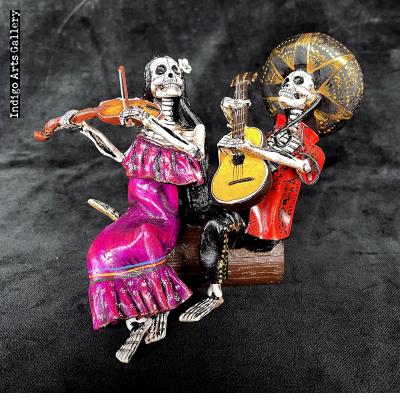

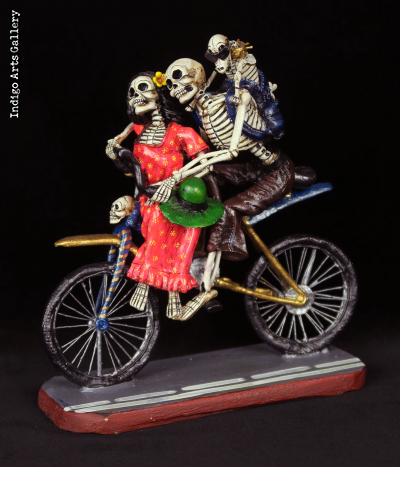

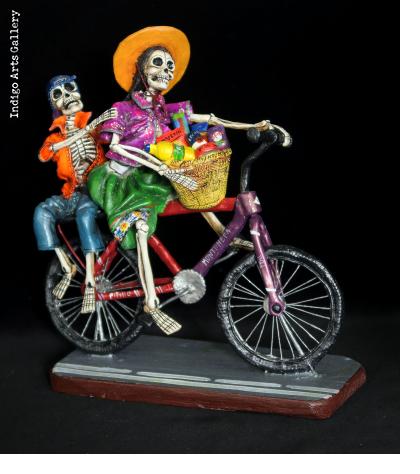

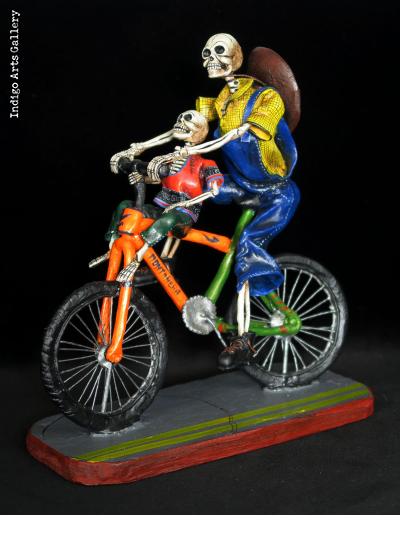

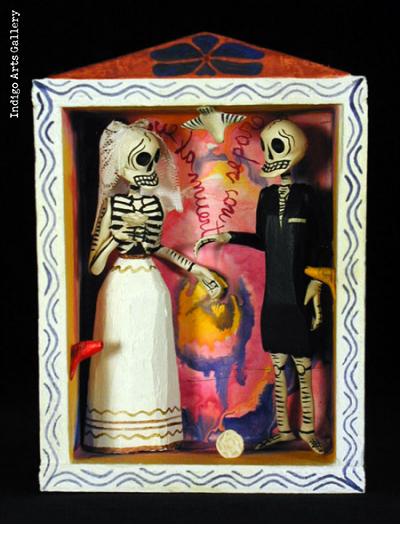

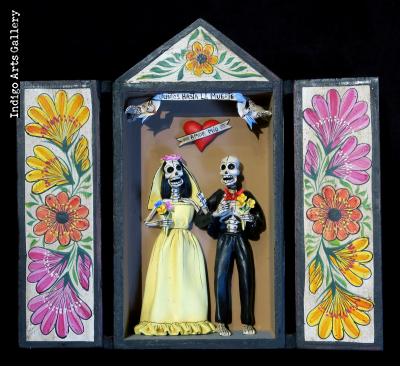

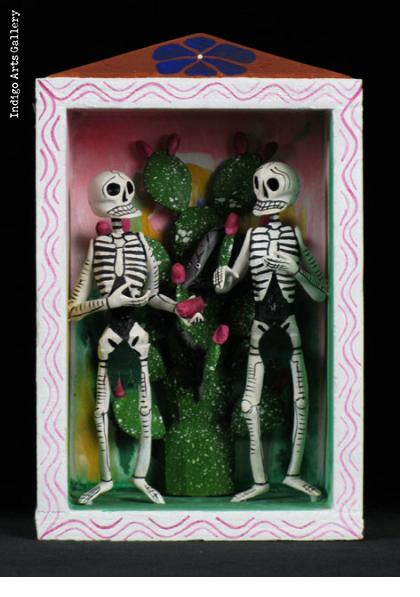

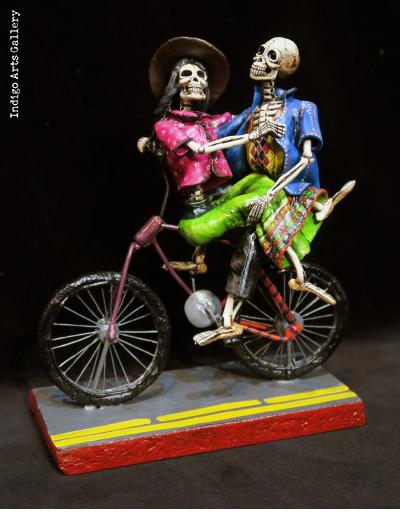

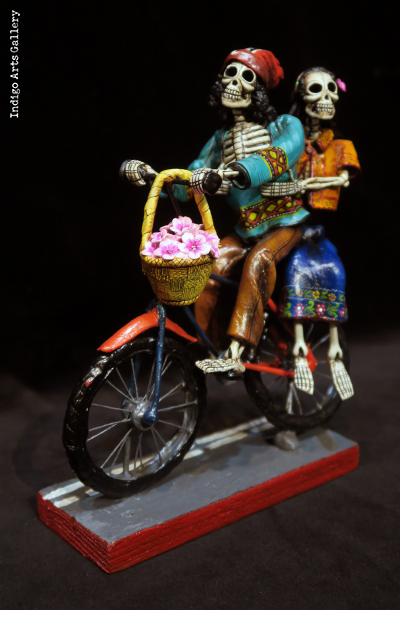

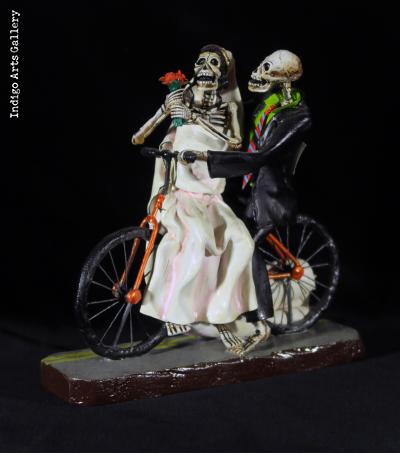

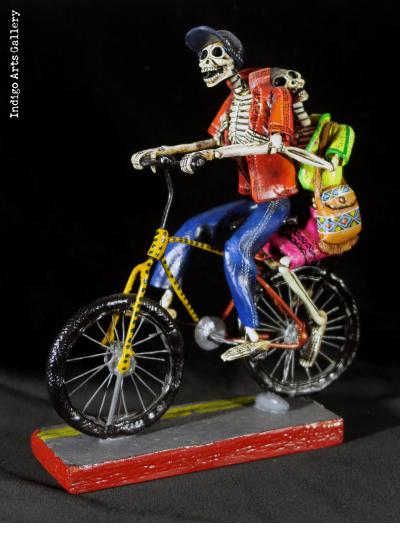

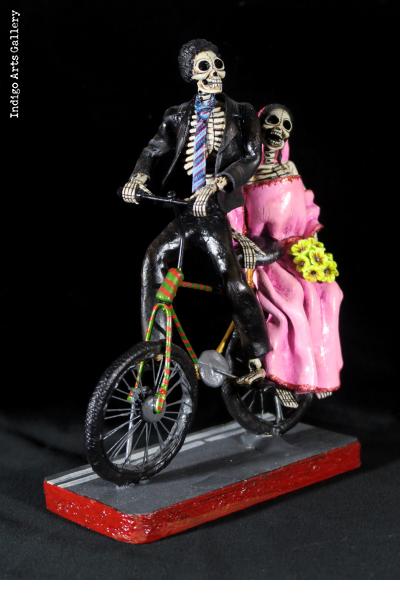

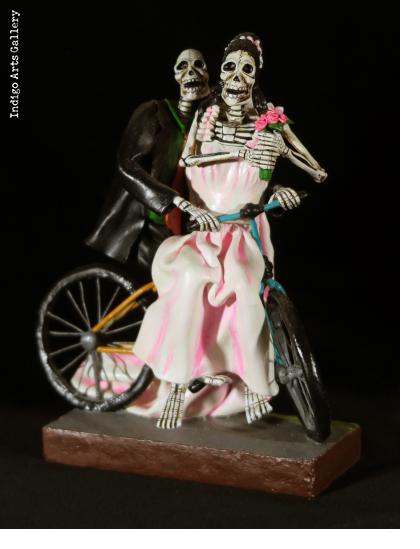

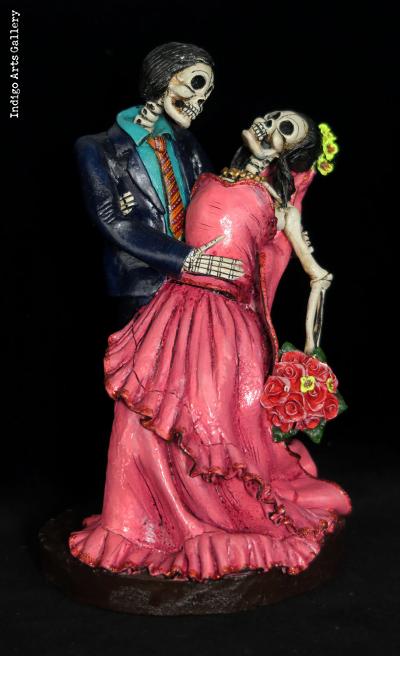

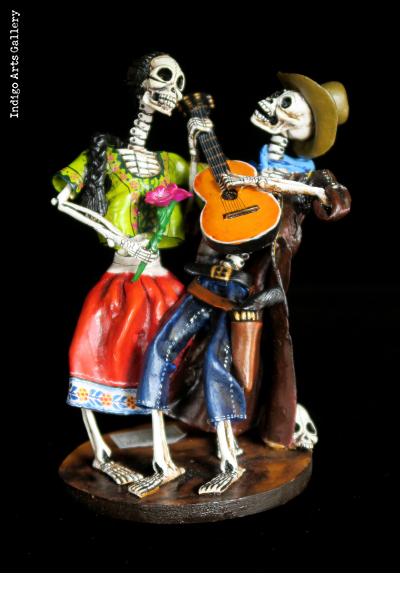

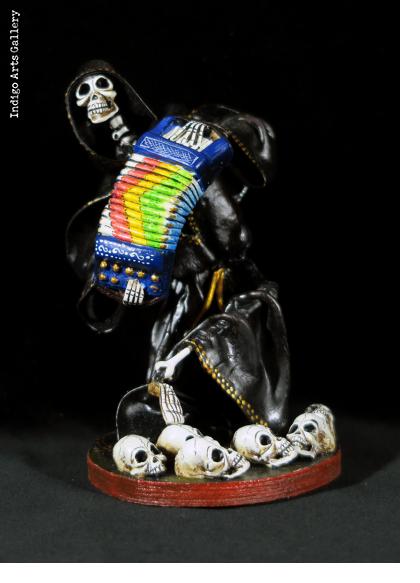

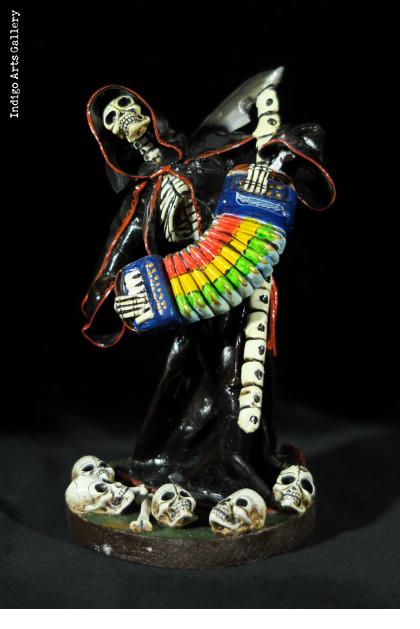

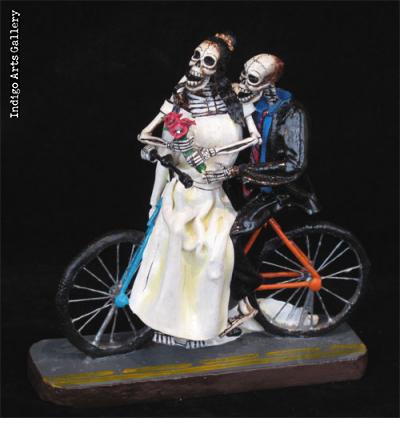

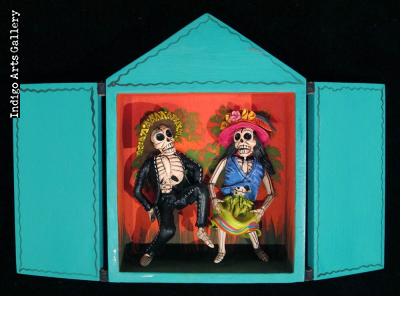

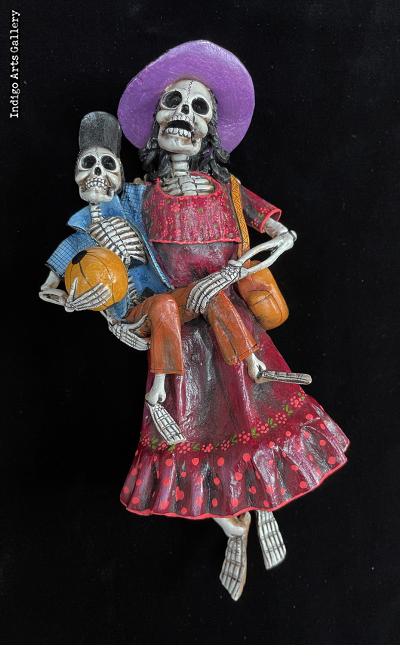

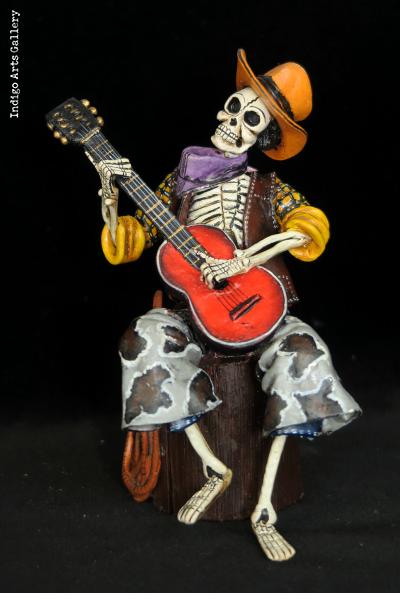

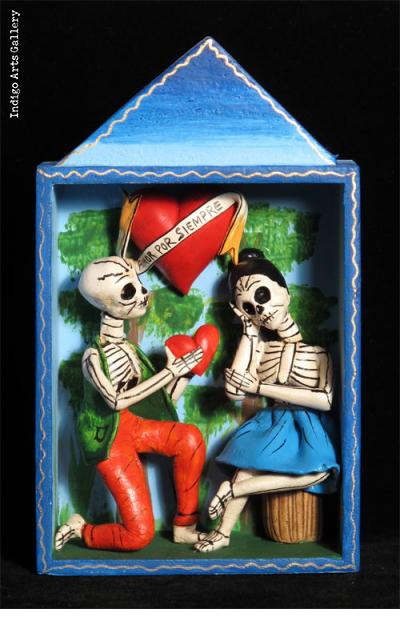

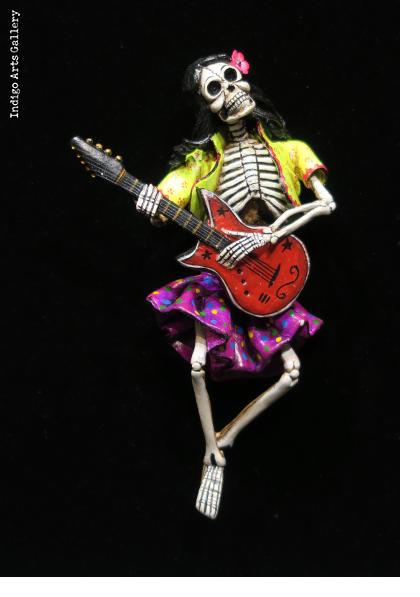

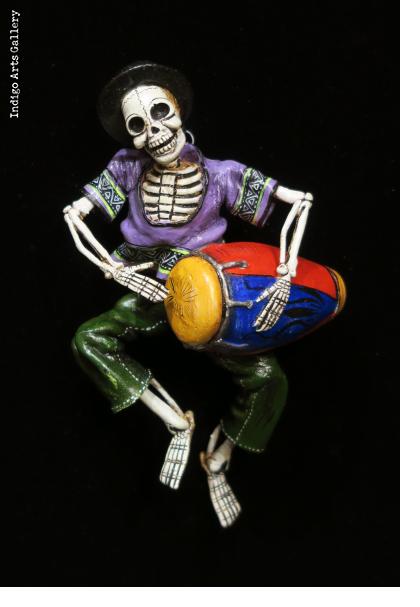

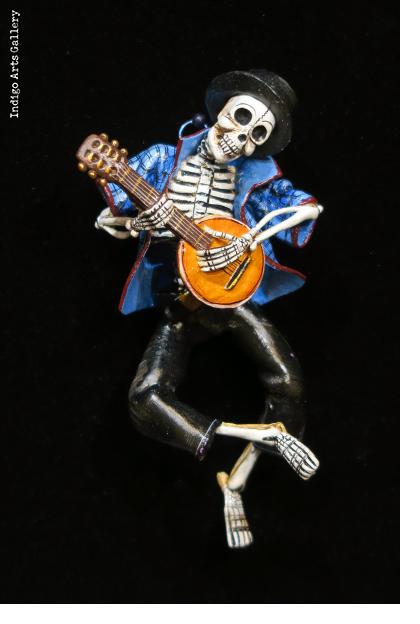

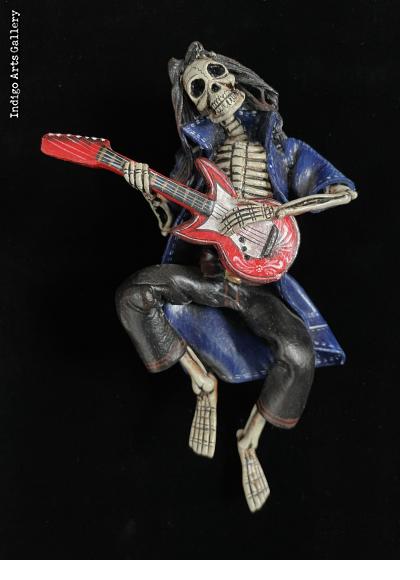

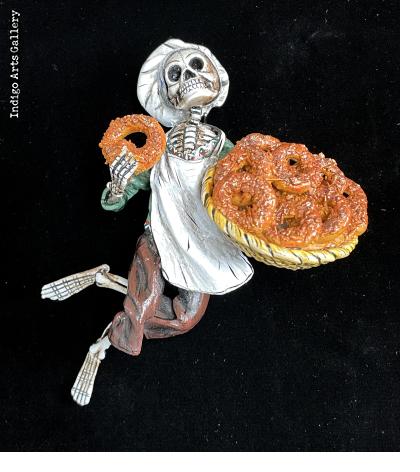

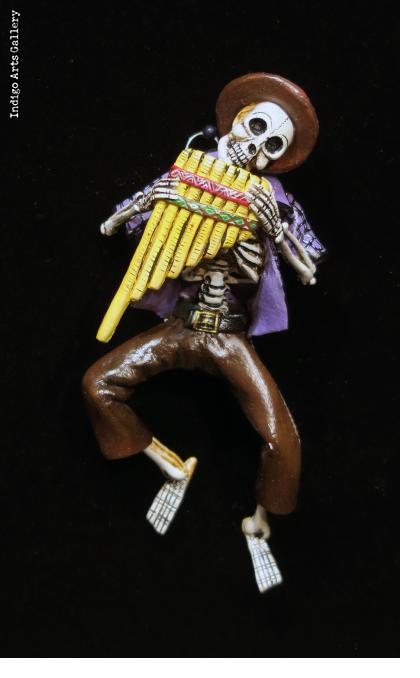

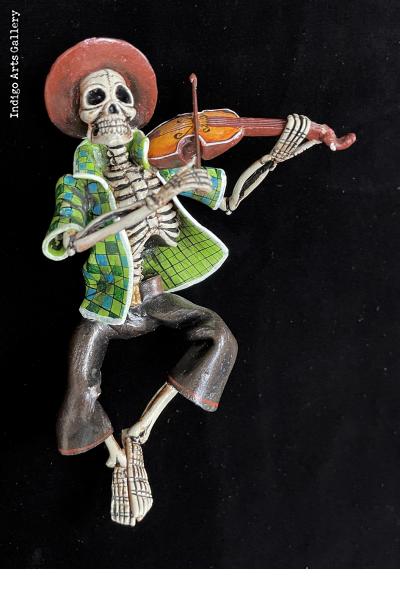

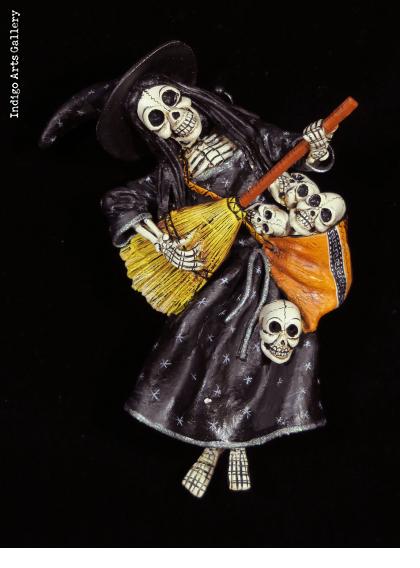

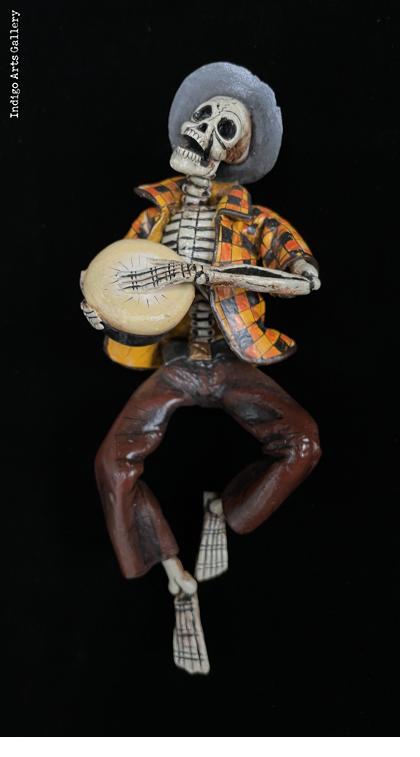

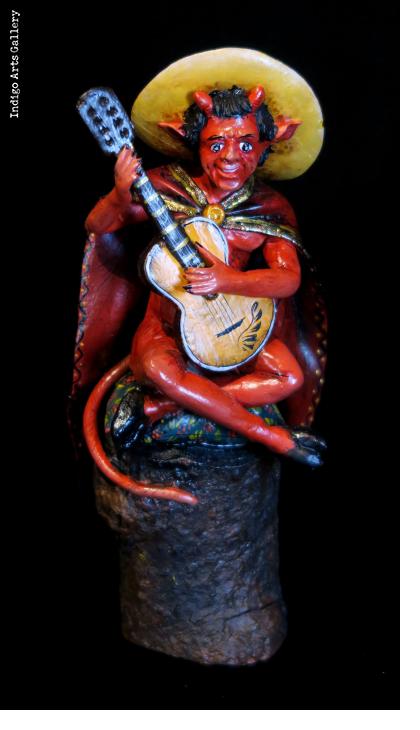

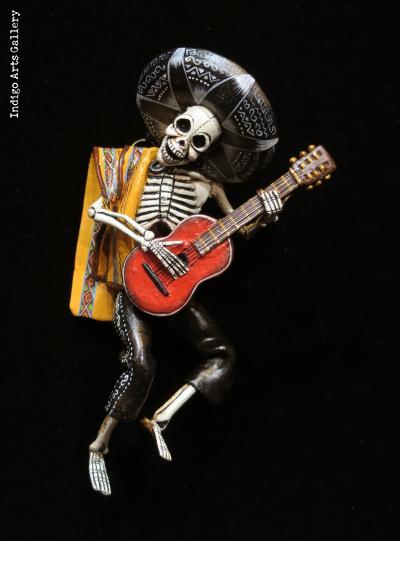

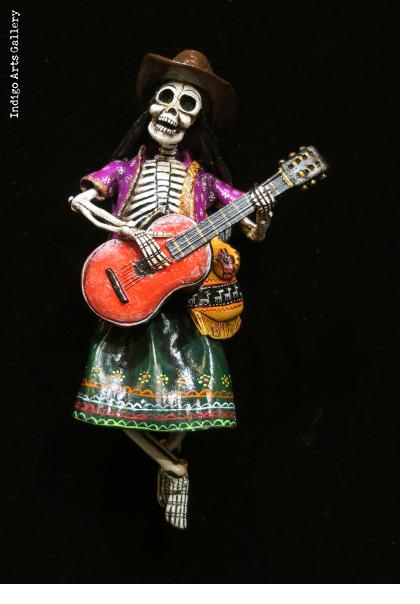

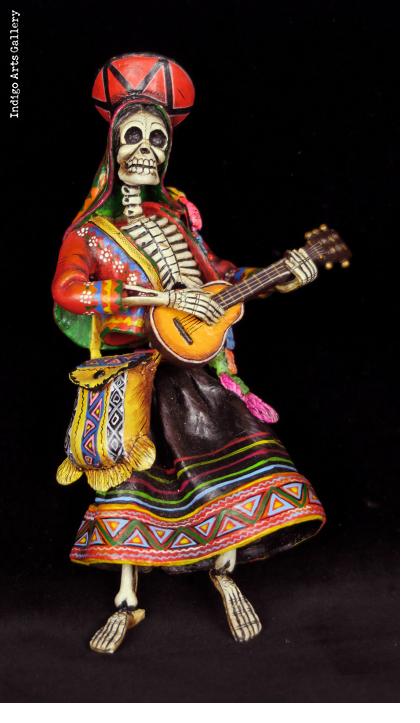

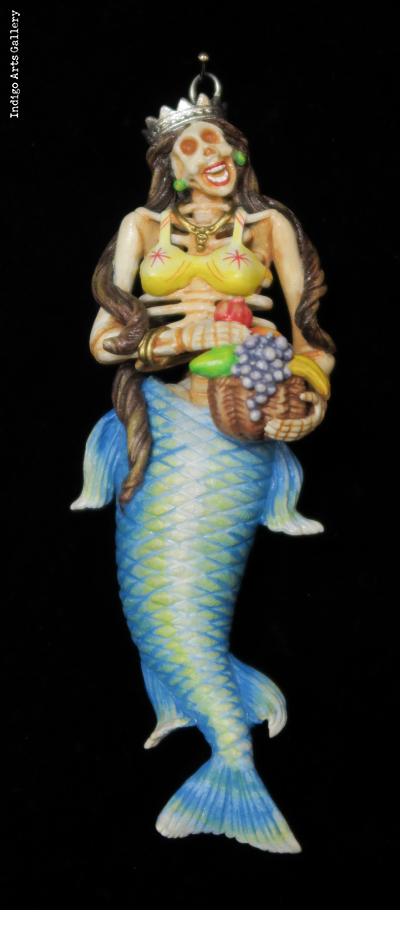

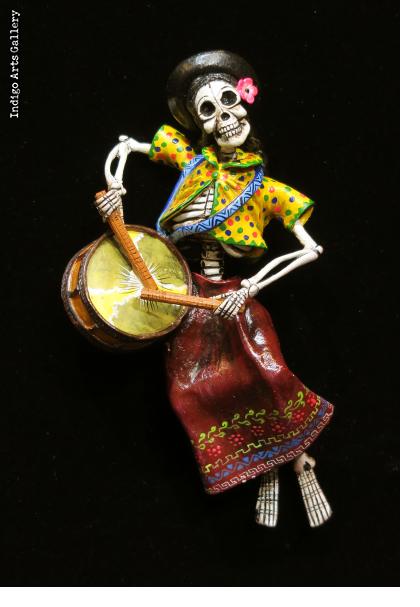

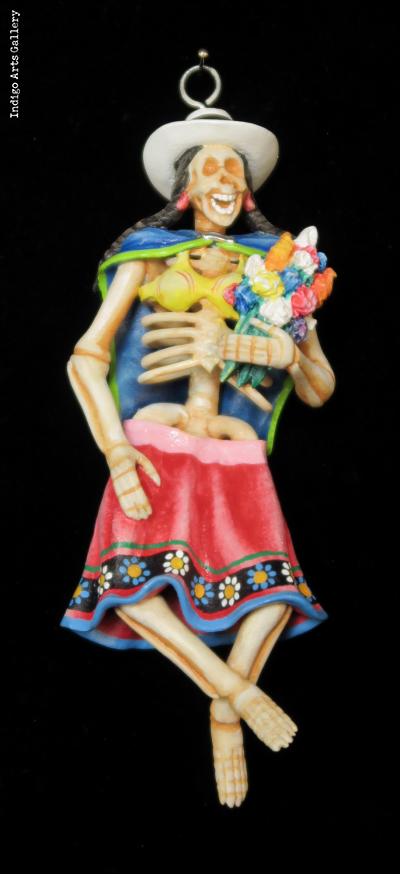

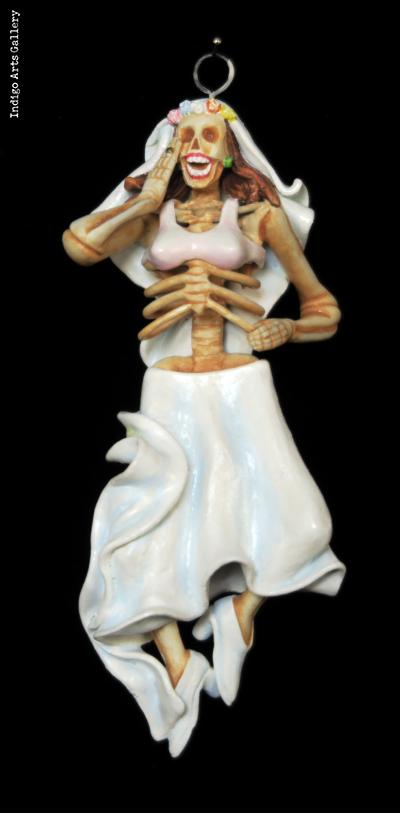

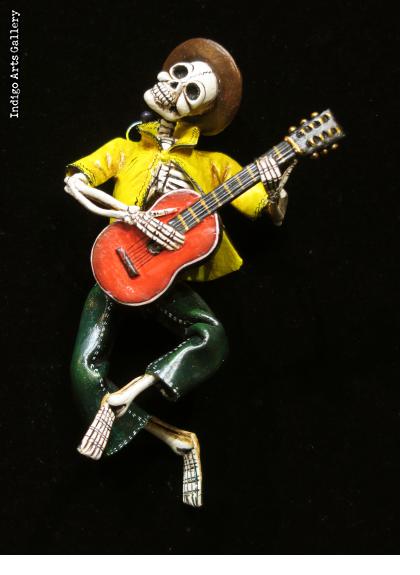

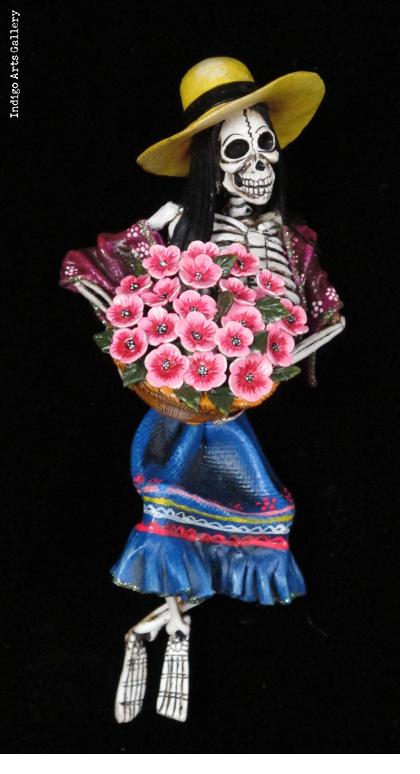

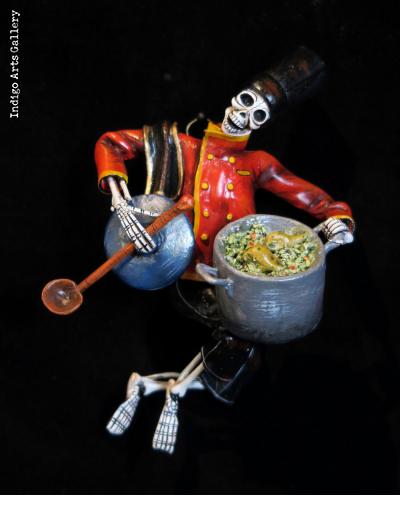

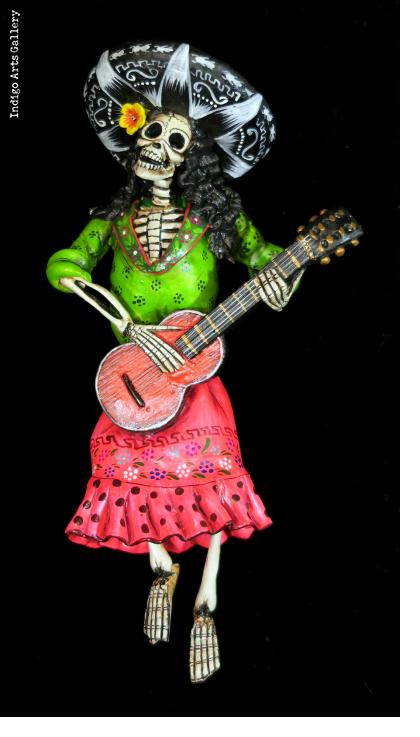

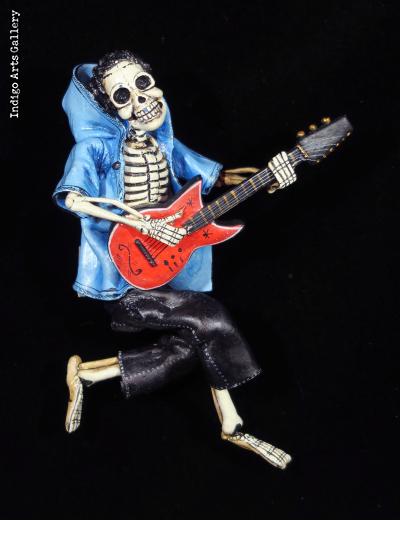

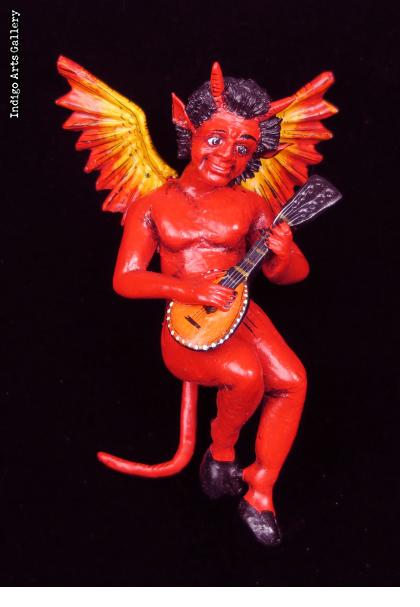

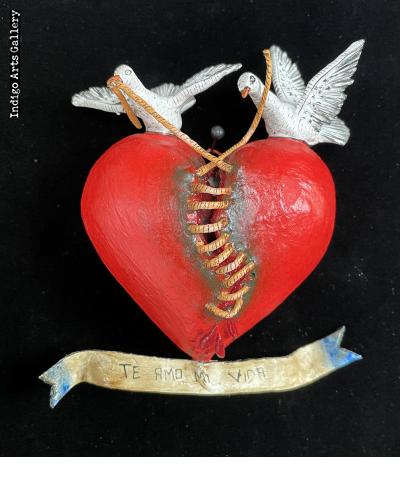

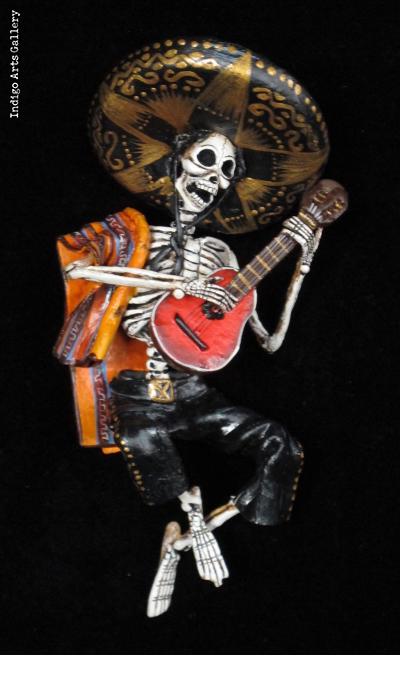

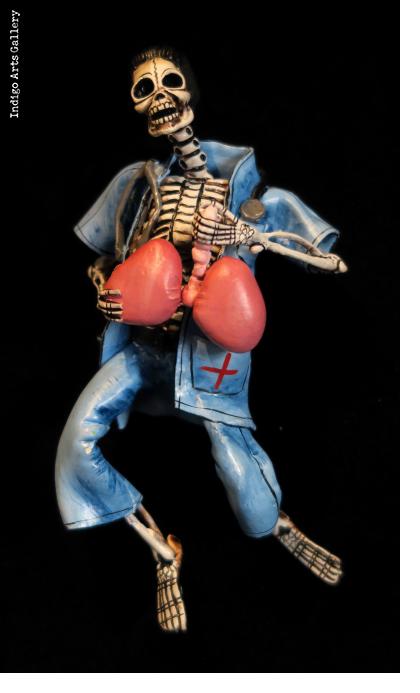

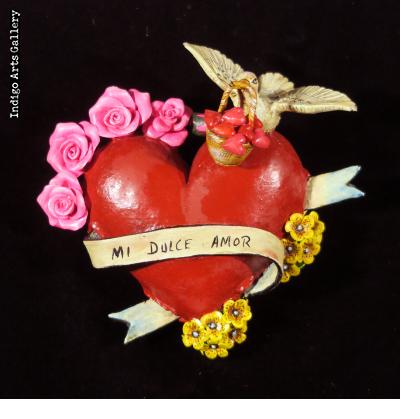

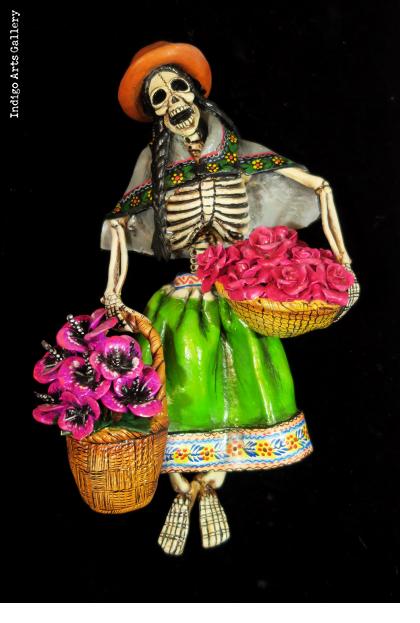

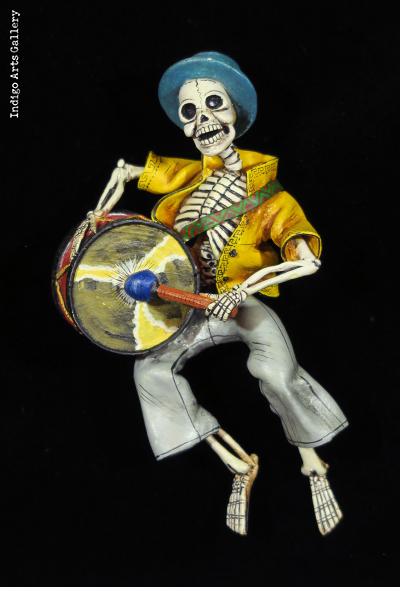

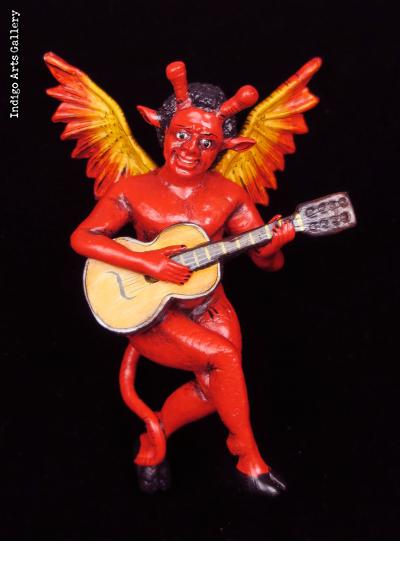

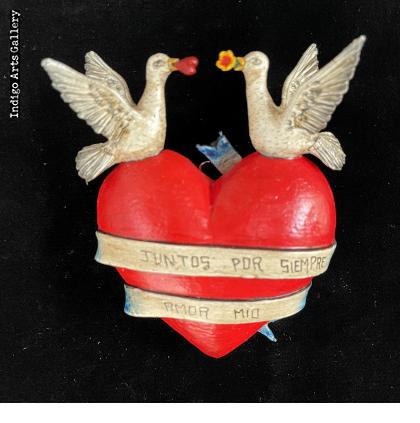

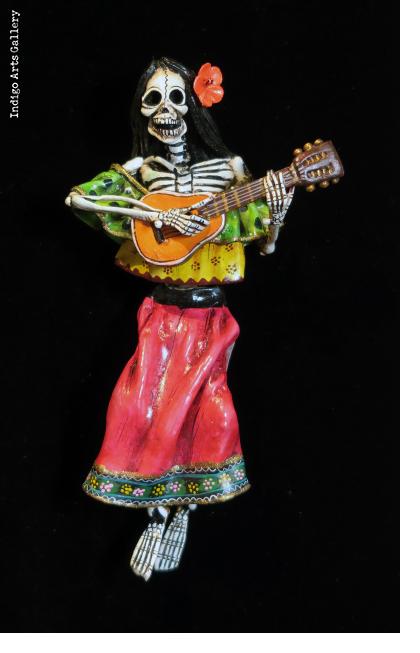

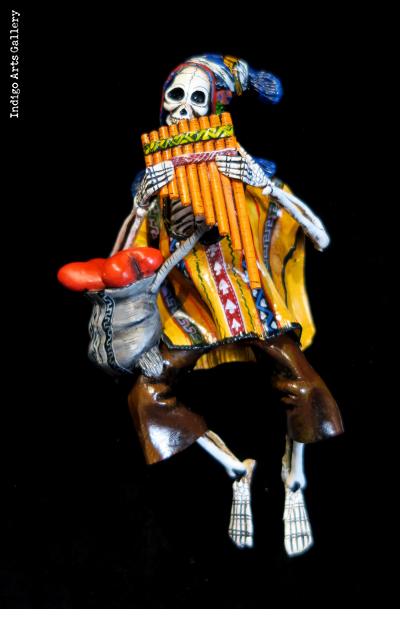

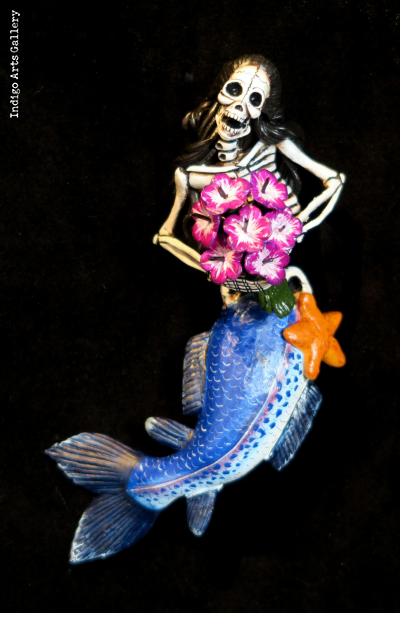

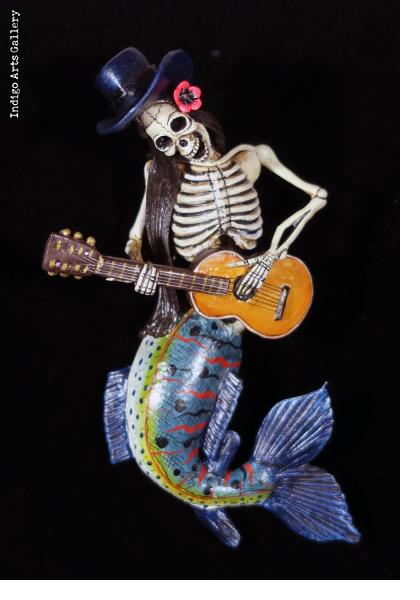

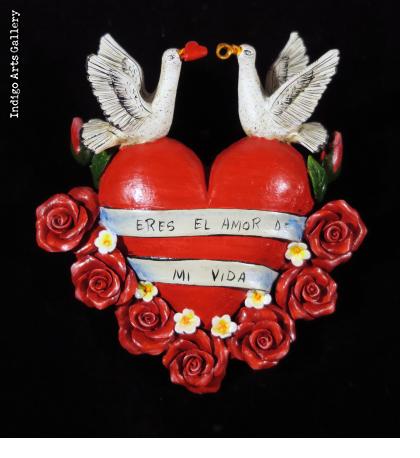

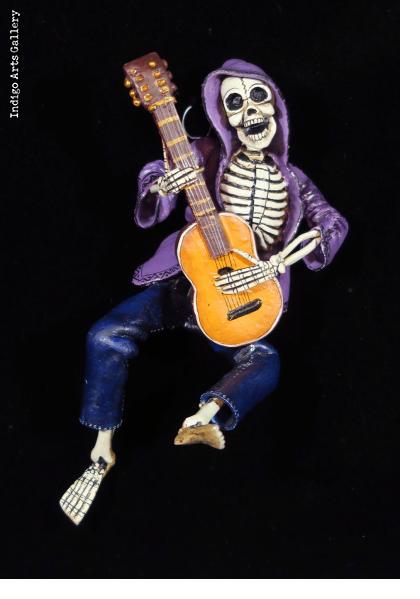

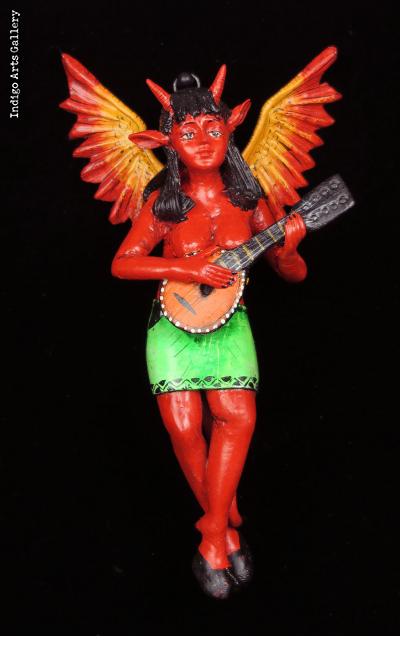

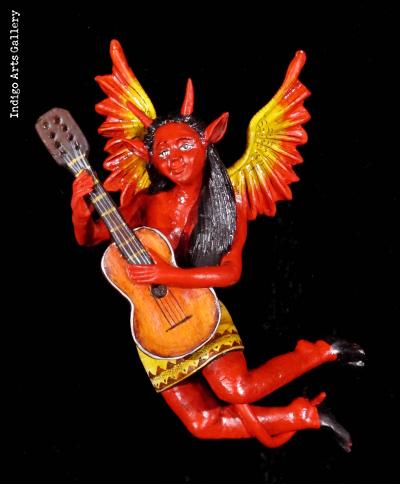

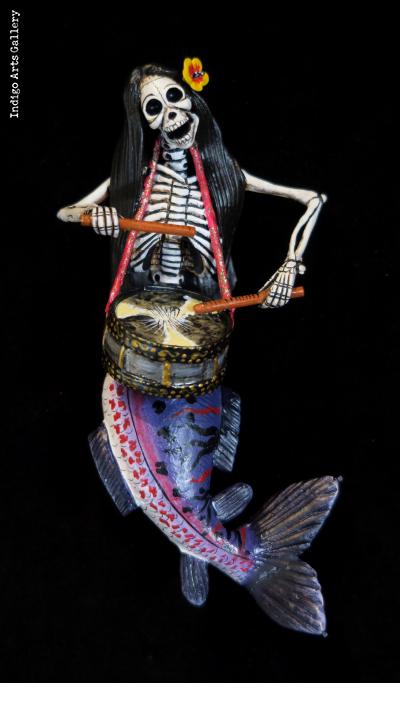

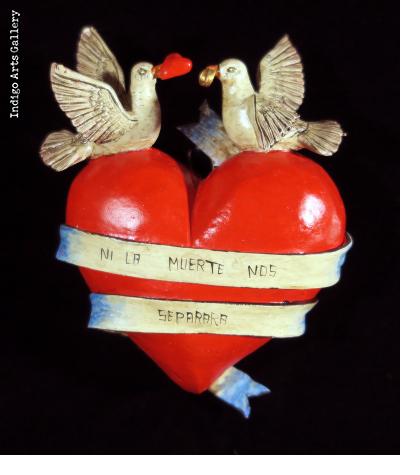

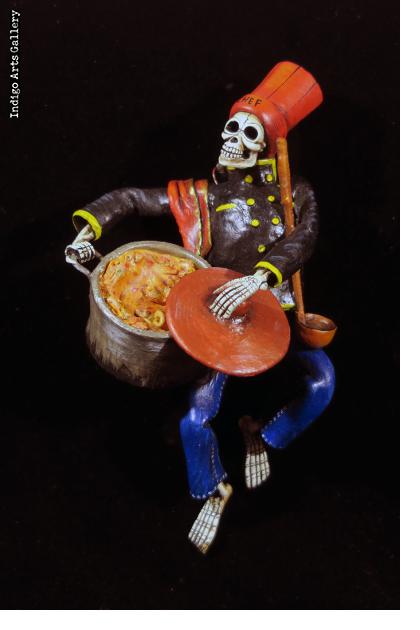

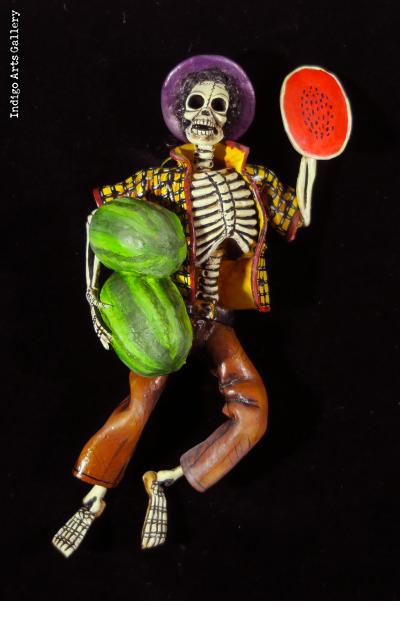

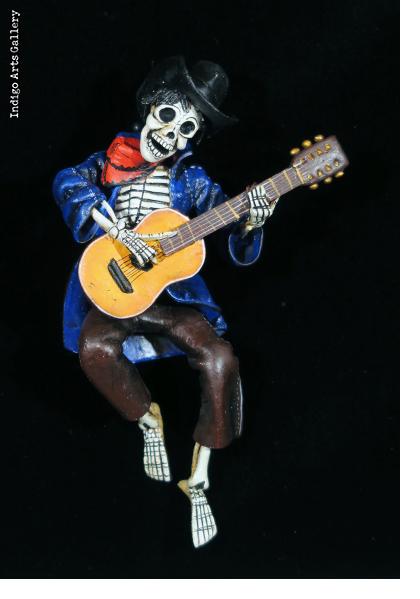

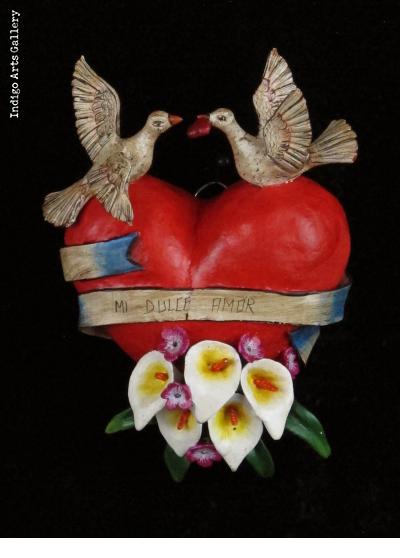

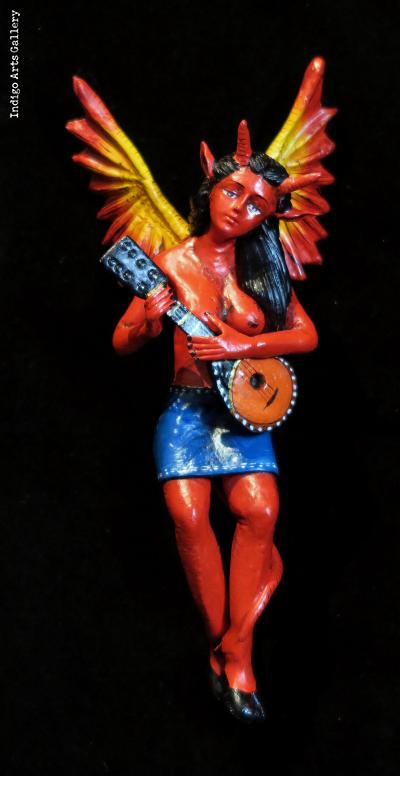

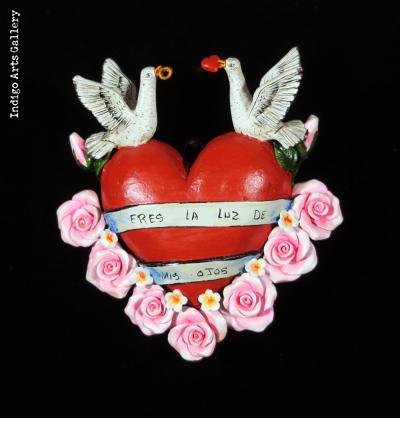

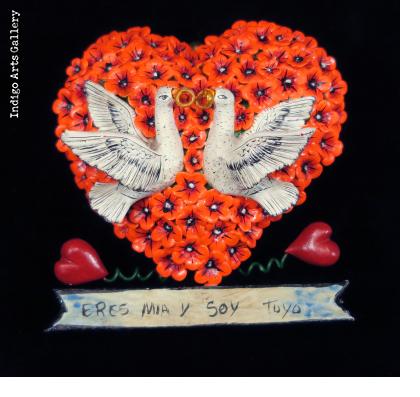

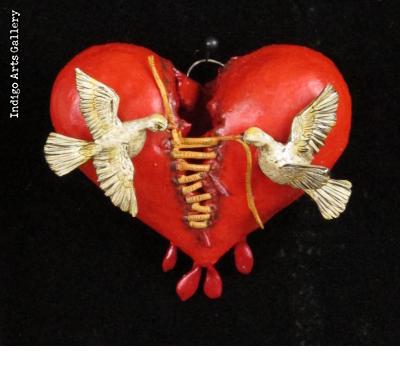

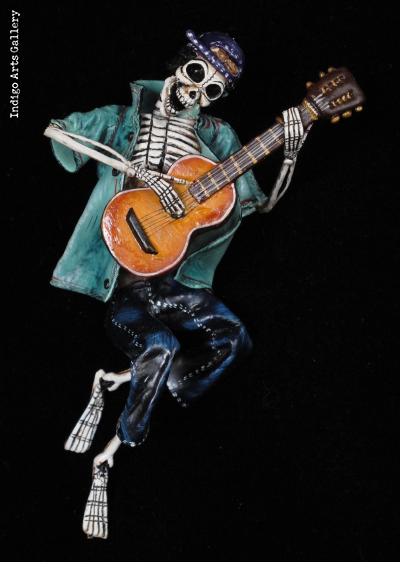

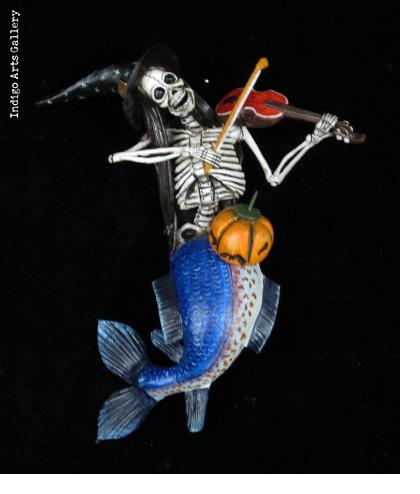

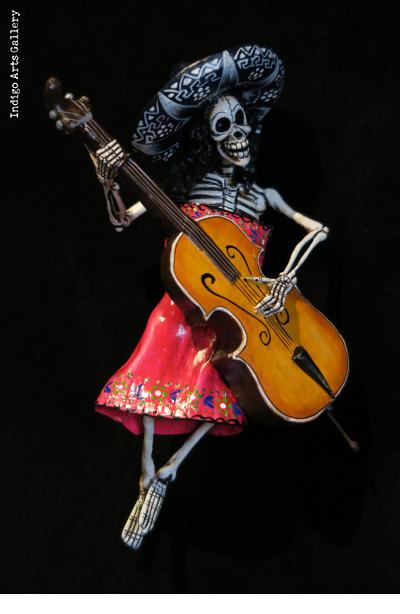

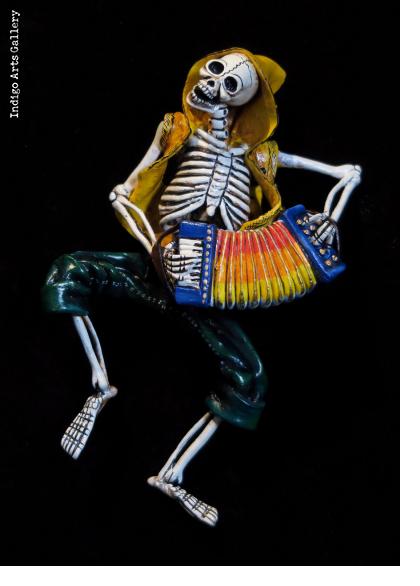

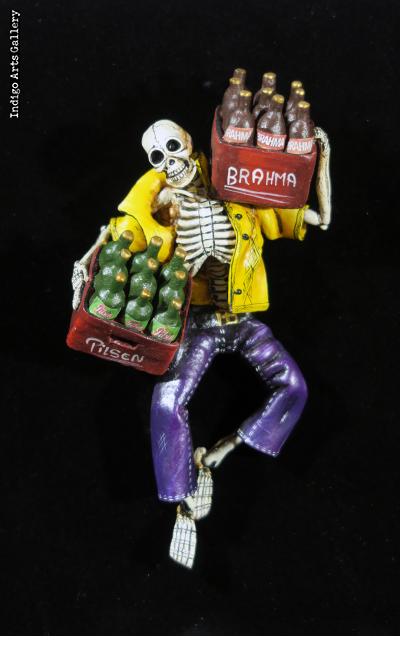

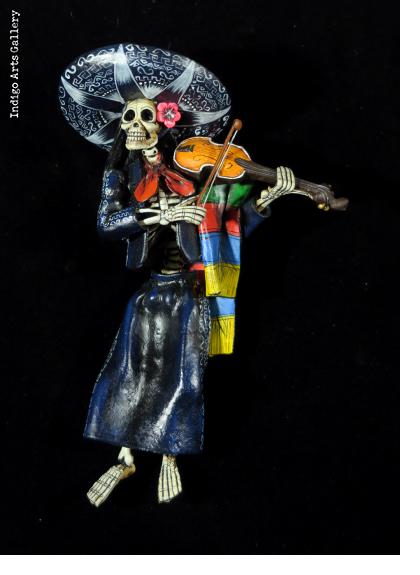

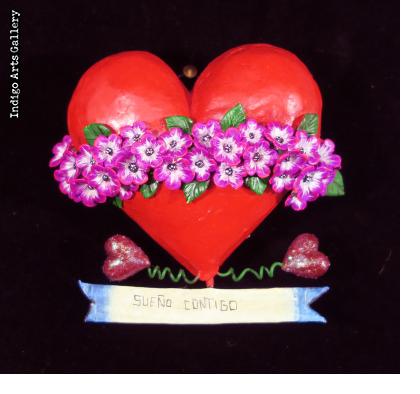

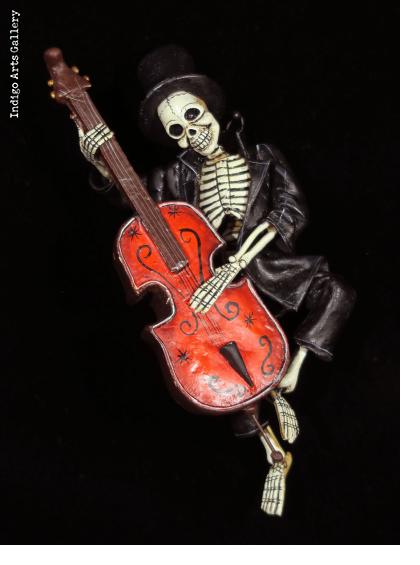

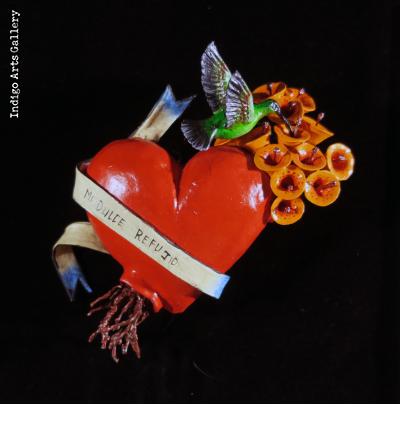

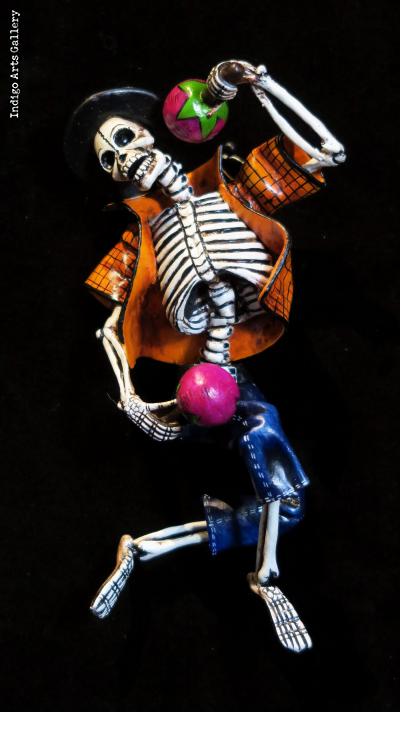

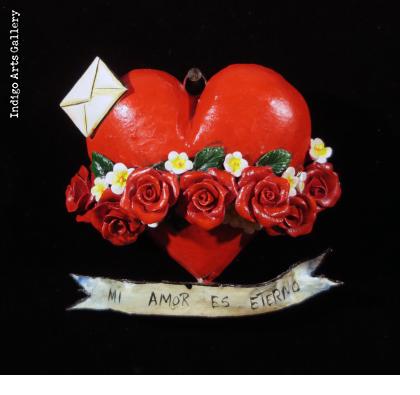

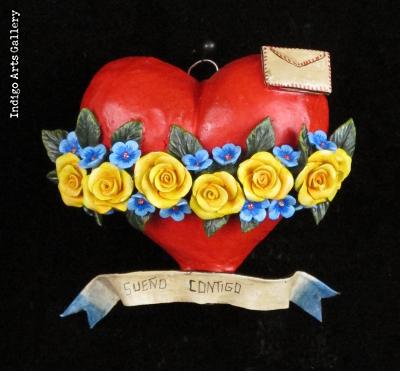

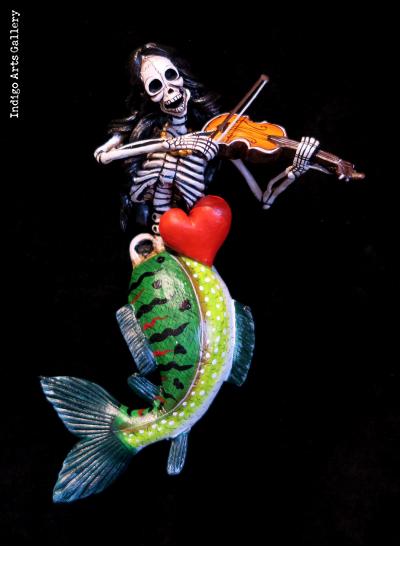

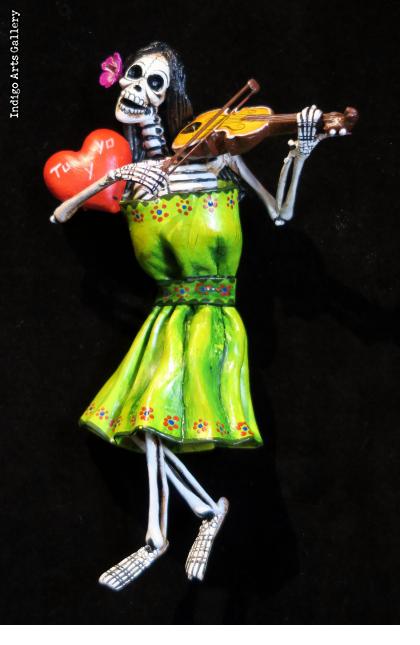

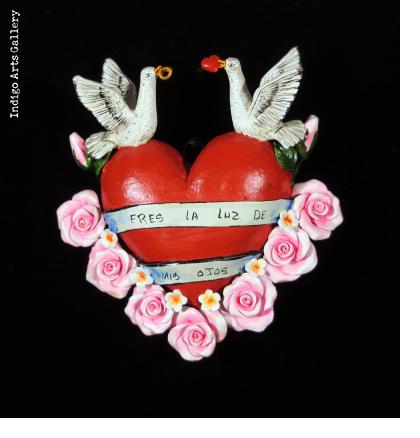

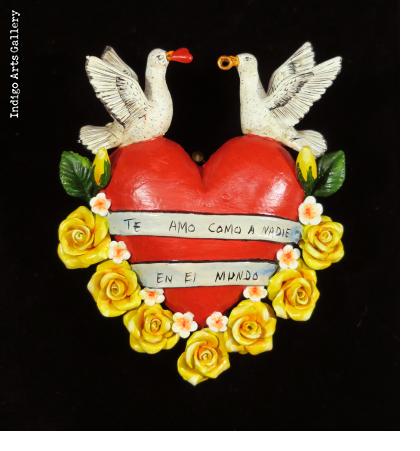

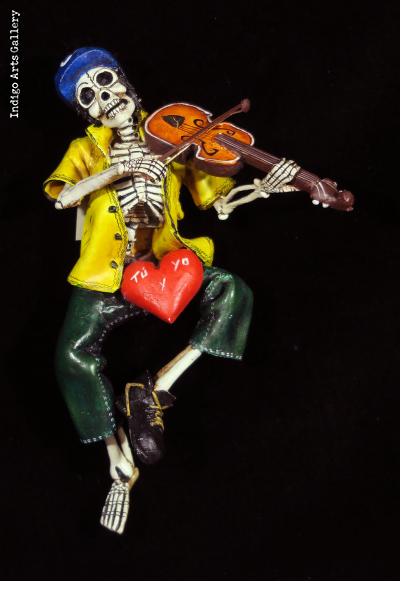

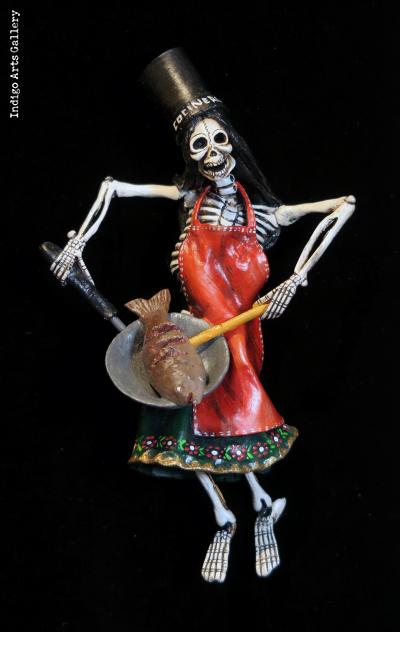

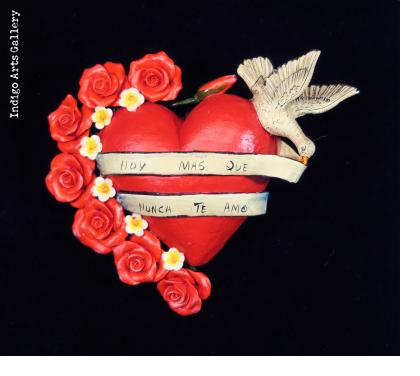

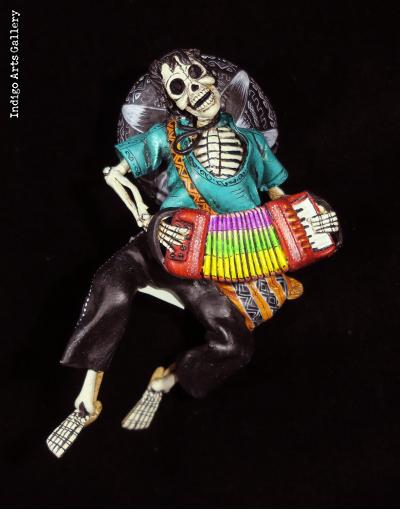

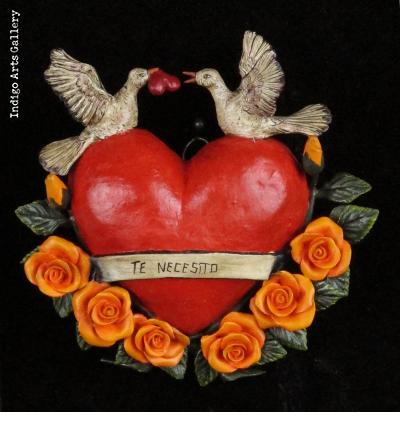

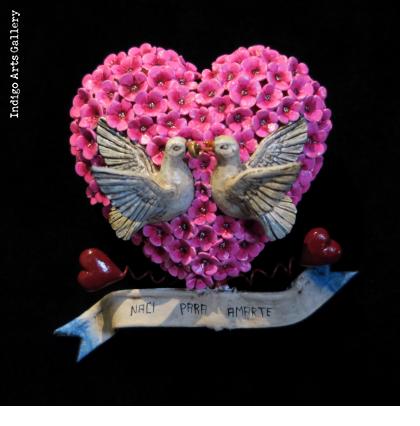

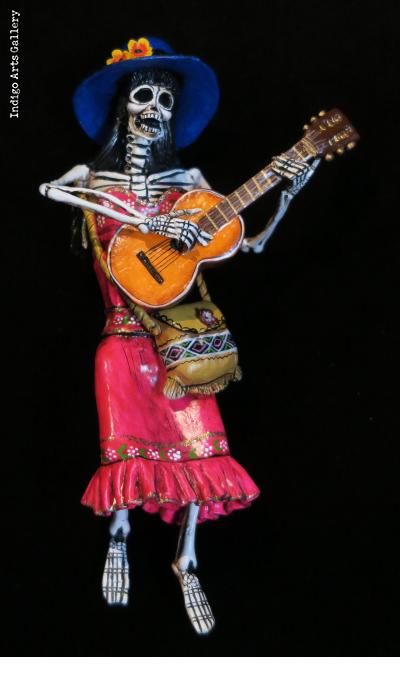

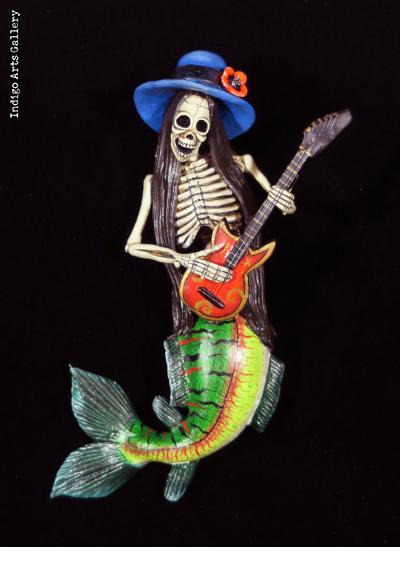

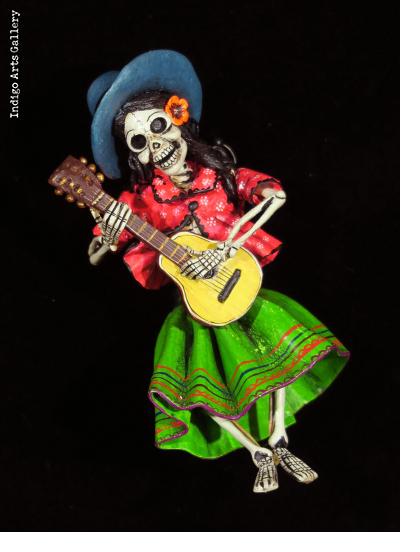

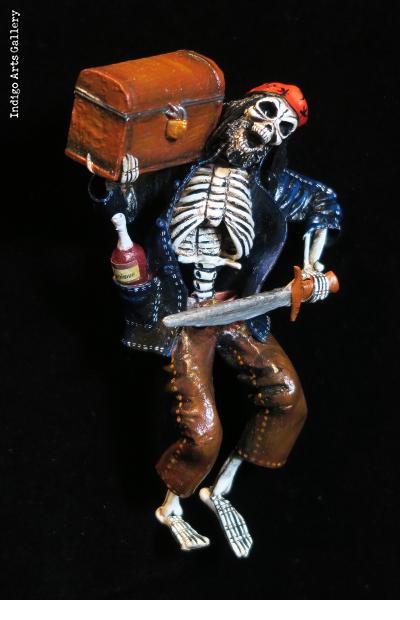

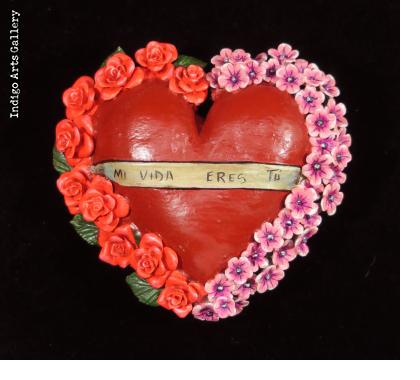

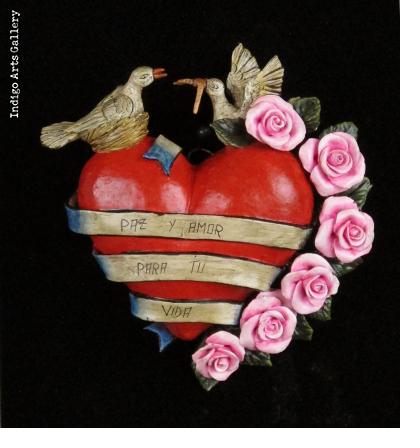

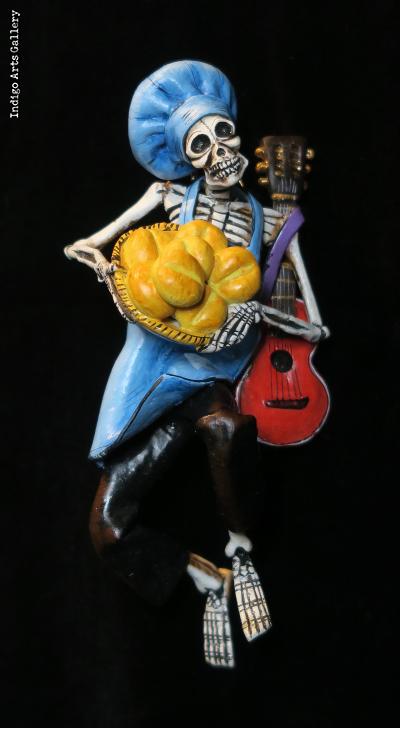

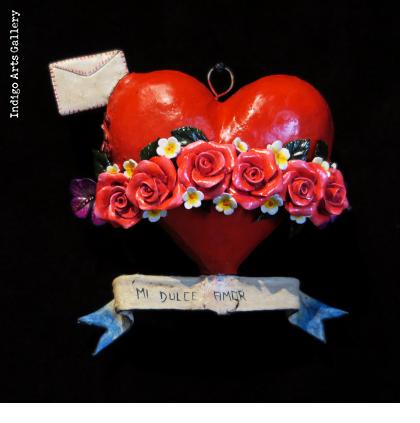

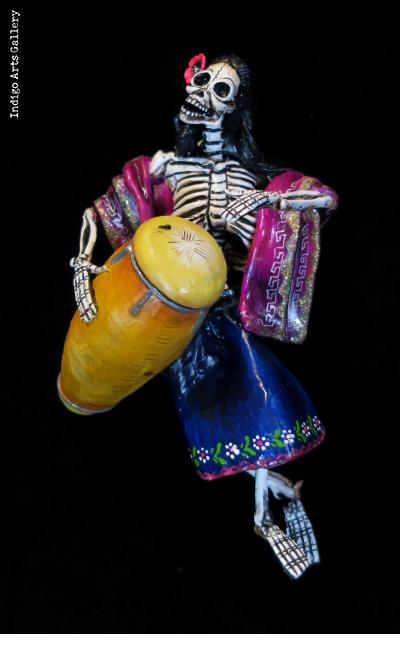

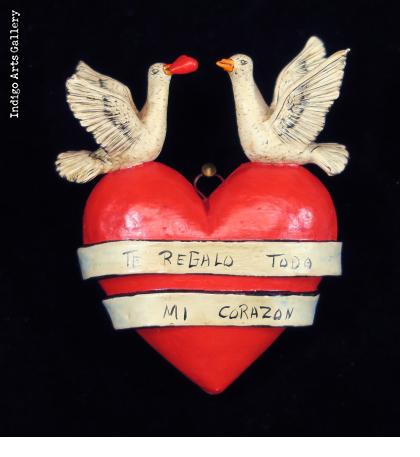

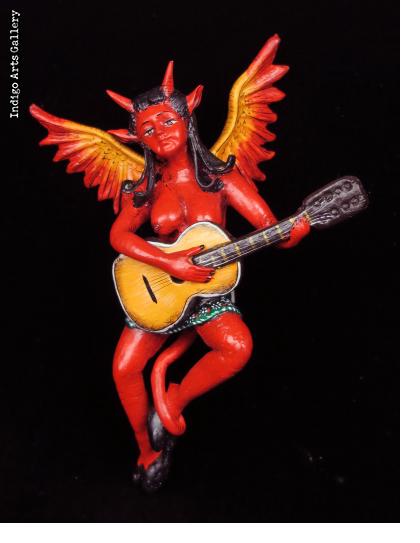

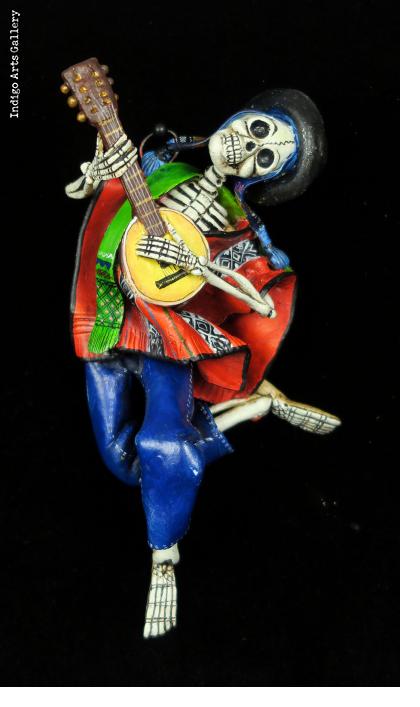

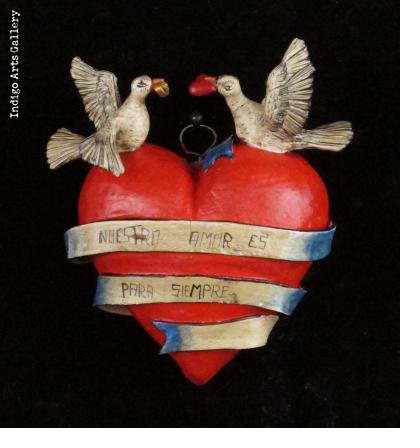

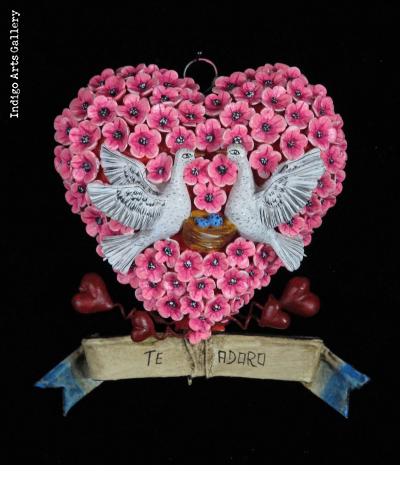

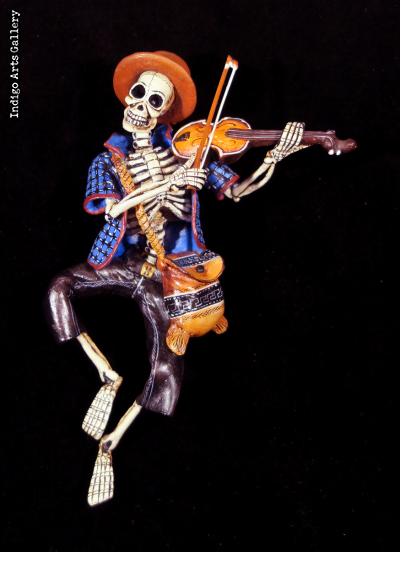

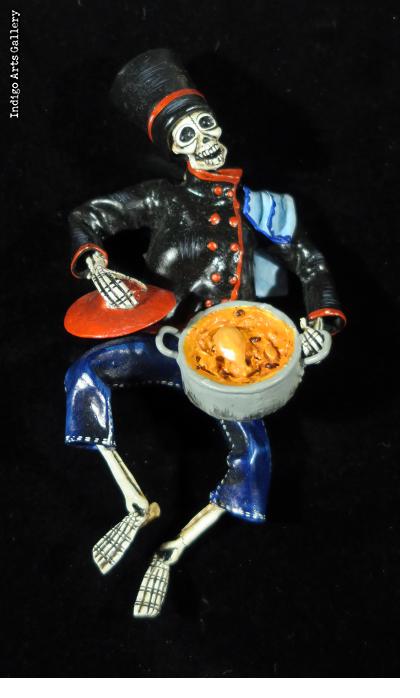

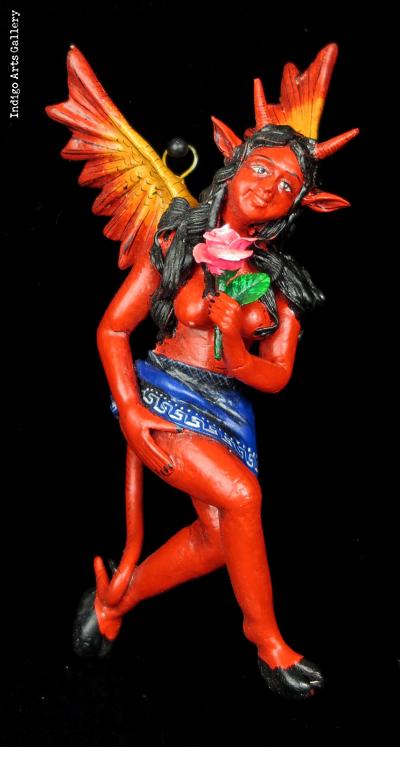

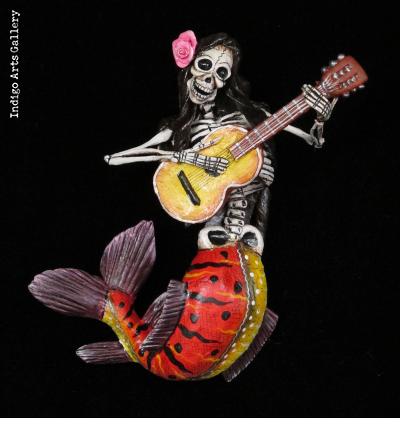

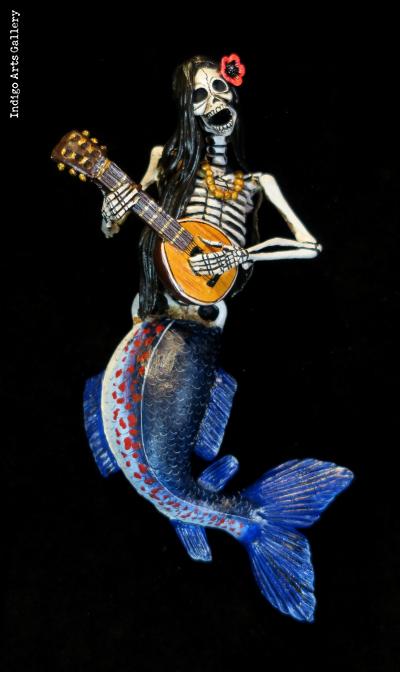

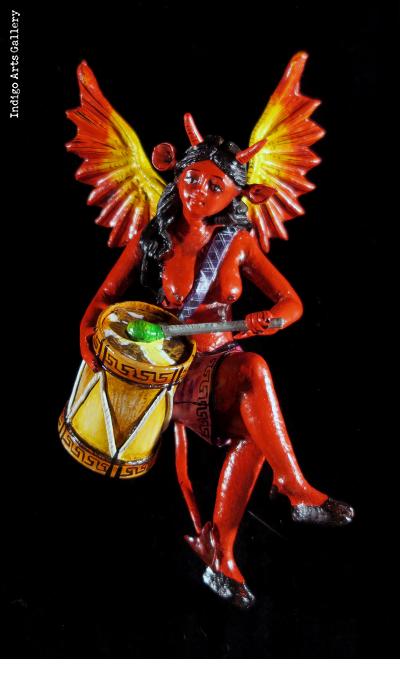

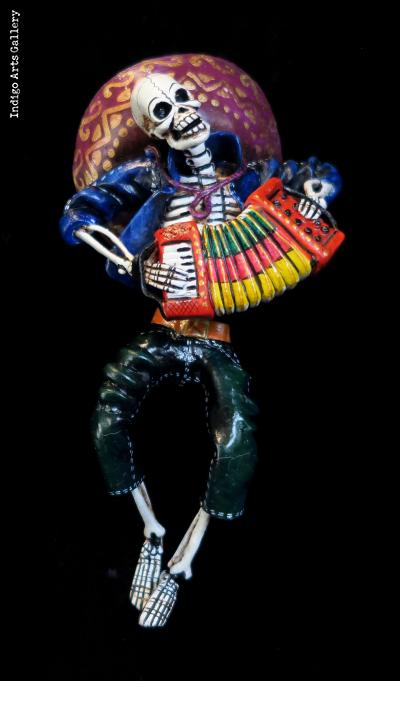

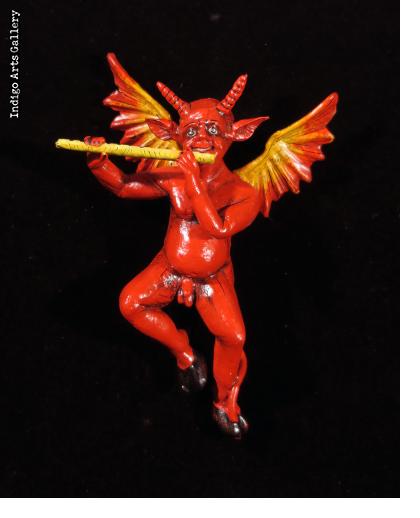

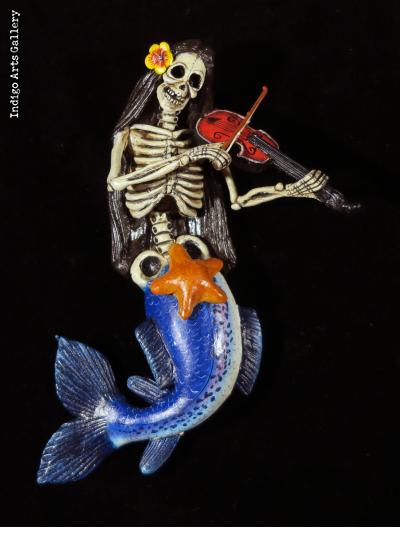

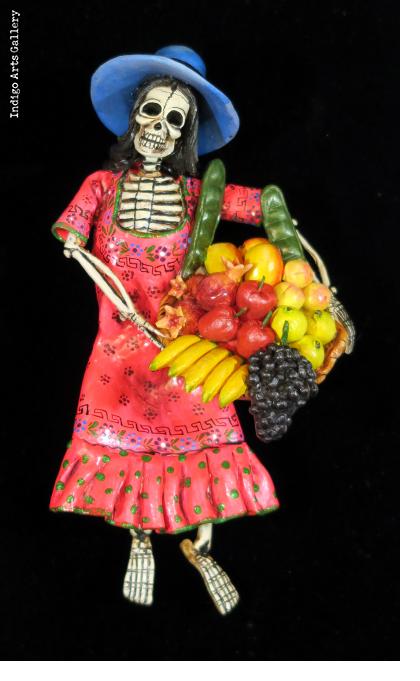

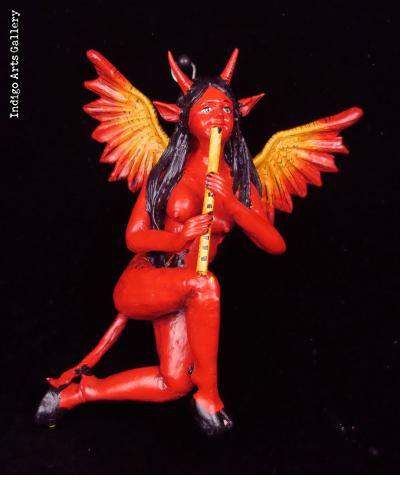

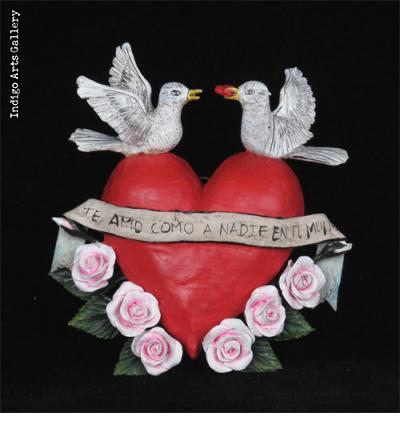

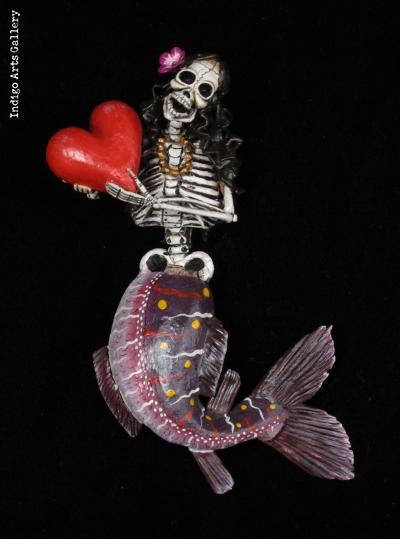

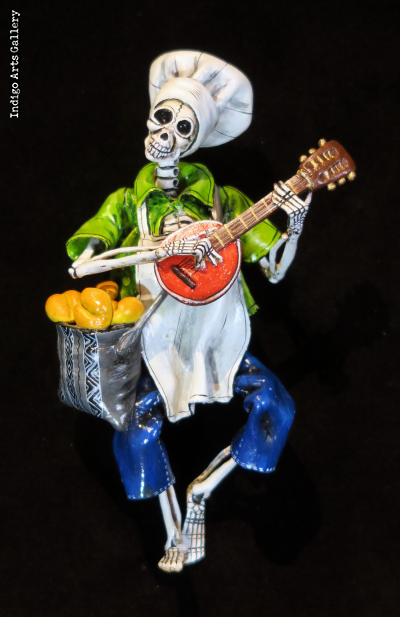

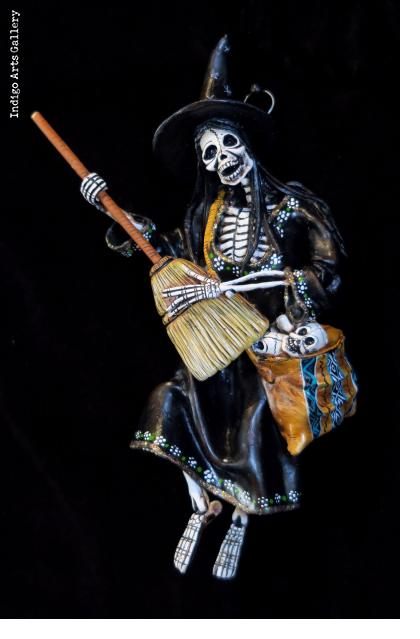

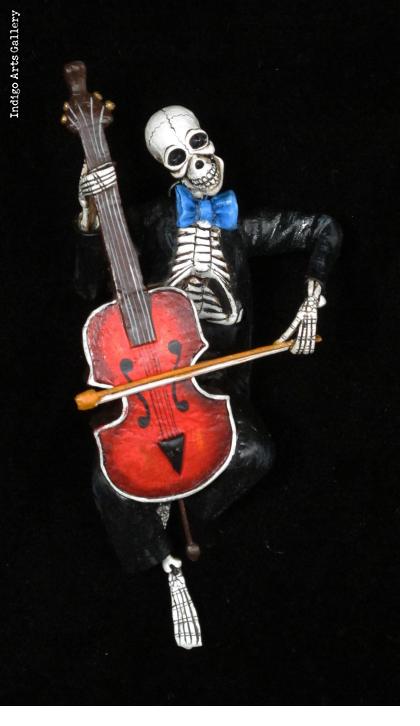

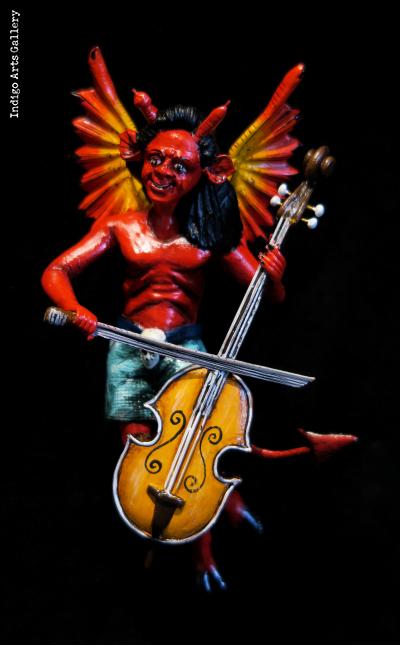

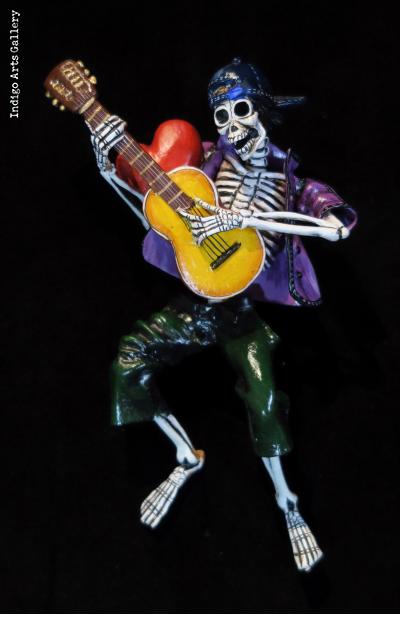

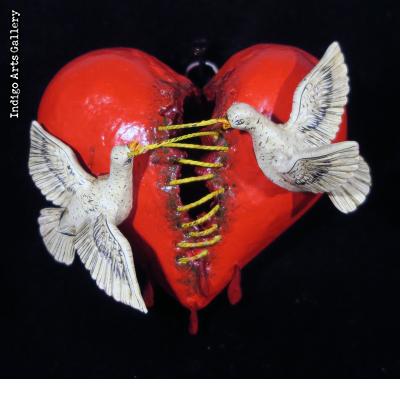

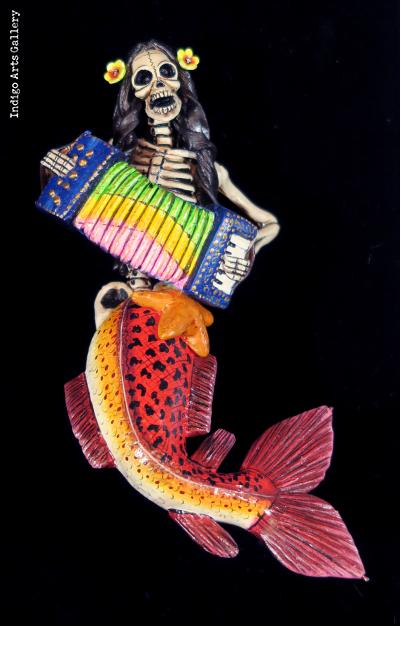

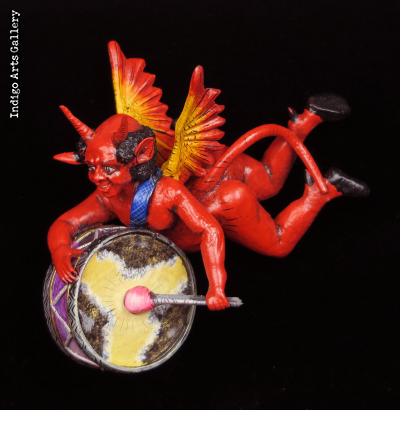

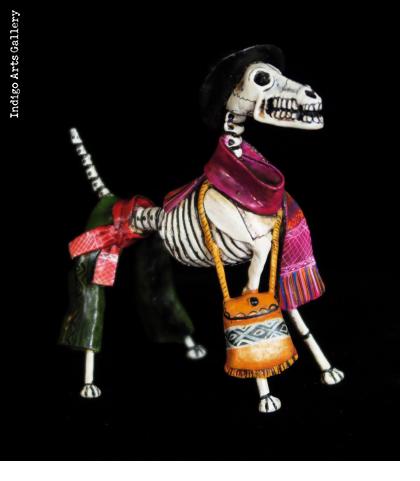

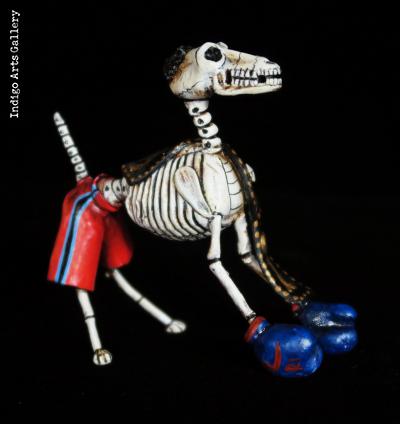

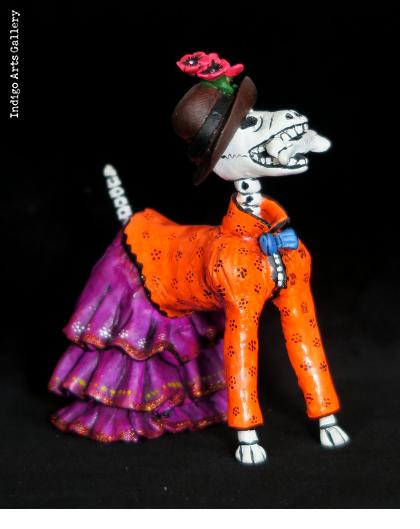

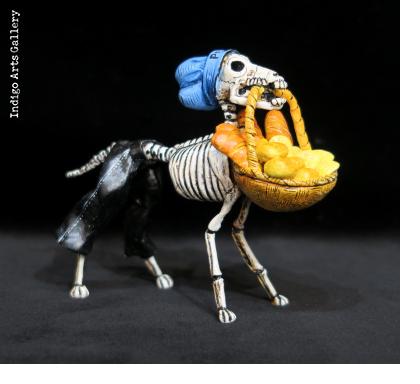

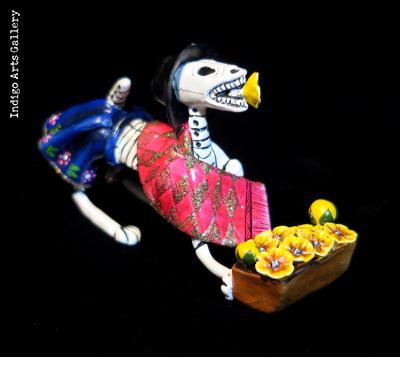

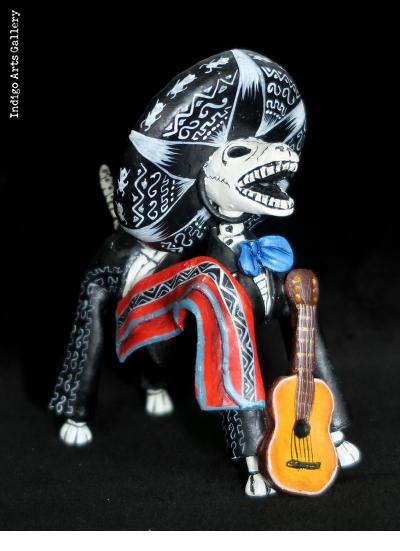

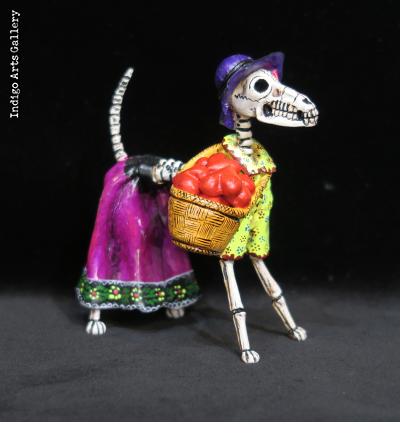

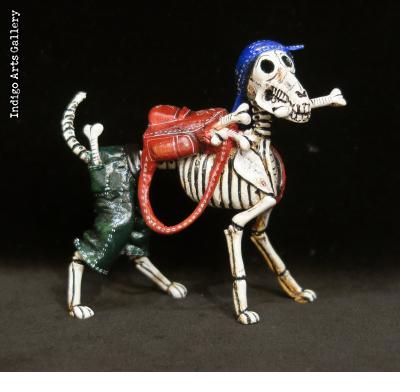

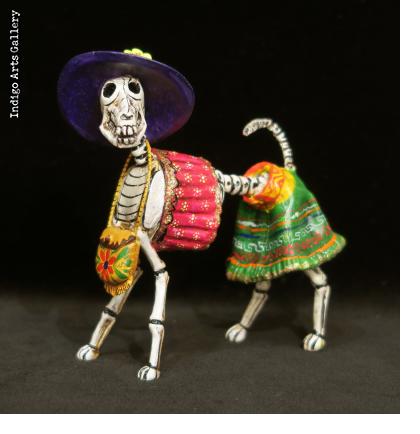

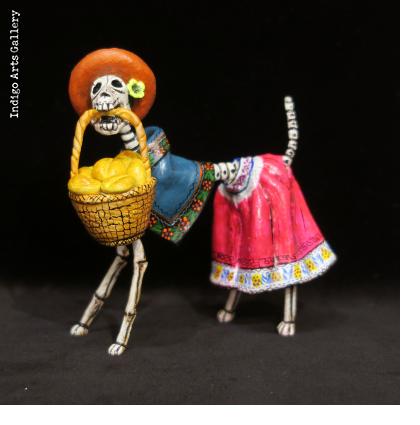

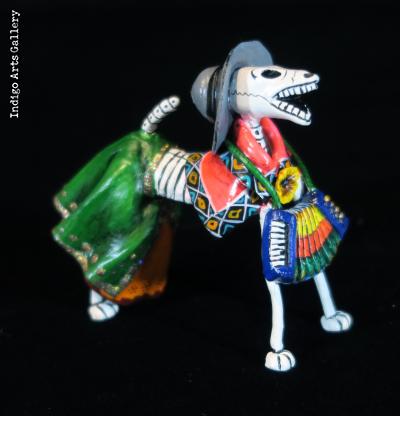

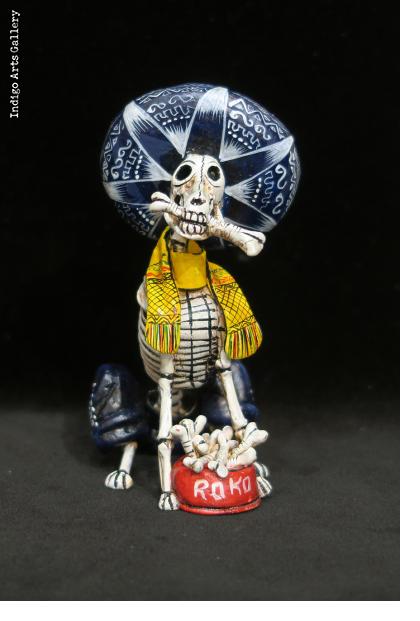

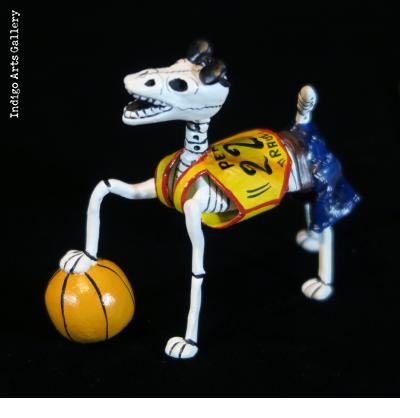

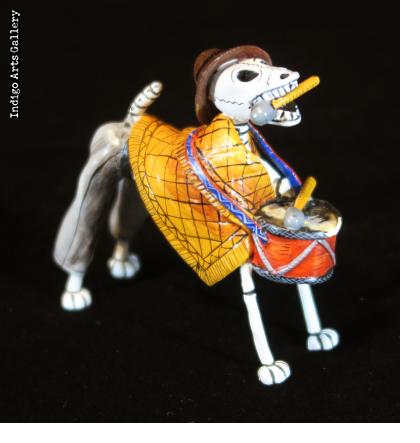

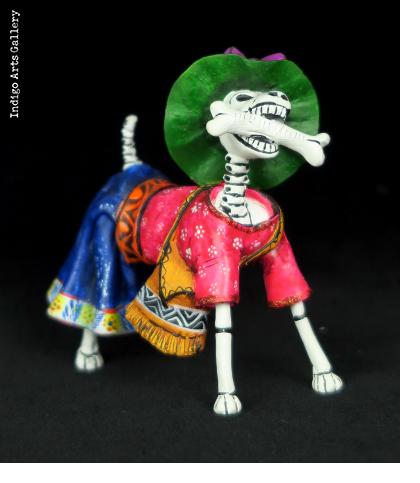

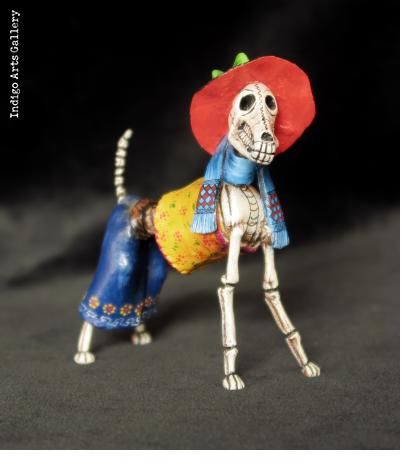

The Sendero Luminoso movement was born in Ayacucho, in the Huamanga region, which was also the most prominent center of retablo making, as well as other indigenous crafts. Many of the best artists, including the renowned Quispé family, fled to safety in Lima. Although the war is now over many of the artists never returned to the countryside. The effect on the retablo art form was profound. New narratives, including scenes of the brutal civil war, entered the repertoire. It also reflected an exposure to urban and even foreign subjects. Works by the master retablista, Claudio Jimenez Quispé, and other members of his extended family, such as Eleudora and Mabilon Jimenez, and Luis and Julia Huamani depict not just saints but scenes of daily life, commerce, romance, political strife and fantasy. Some of their recent work shows strong influences of Mexican folk art as well. In keeping with the season, Shrines of Life includes scenes of death and the underworld to celebrate the upcoming holidays, the Dias de los Muertos (Days of the Dead).

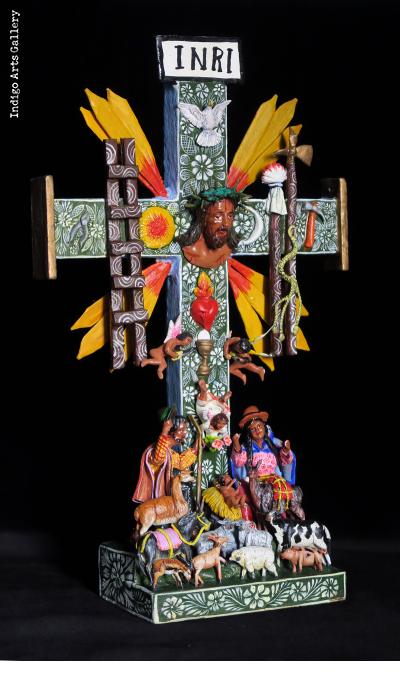

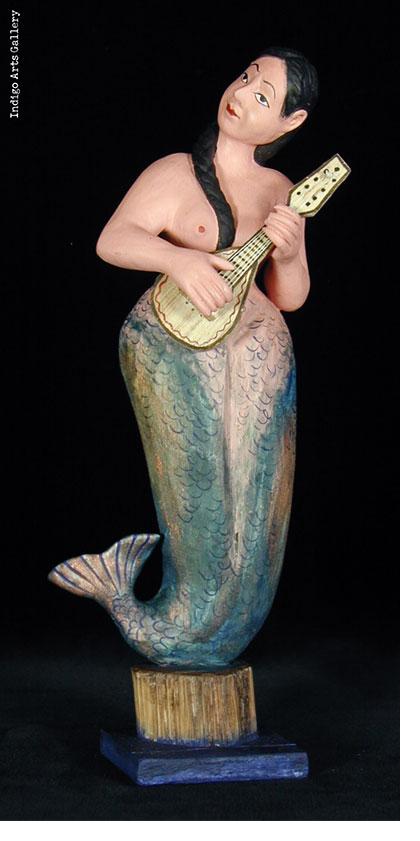

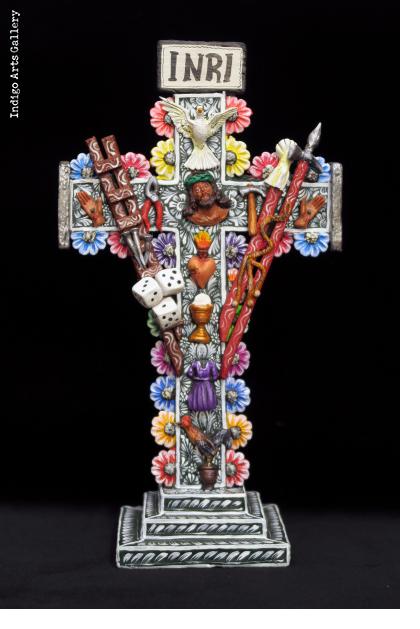

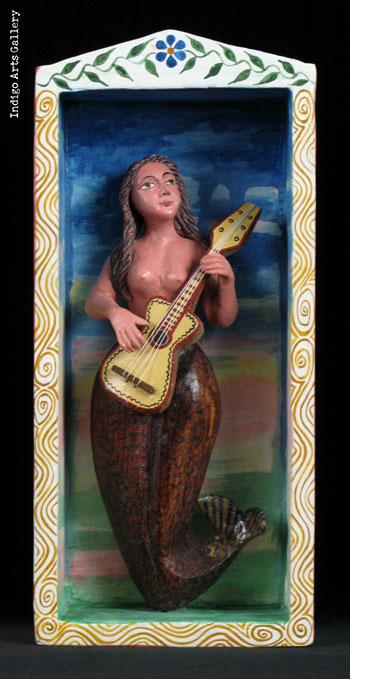

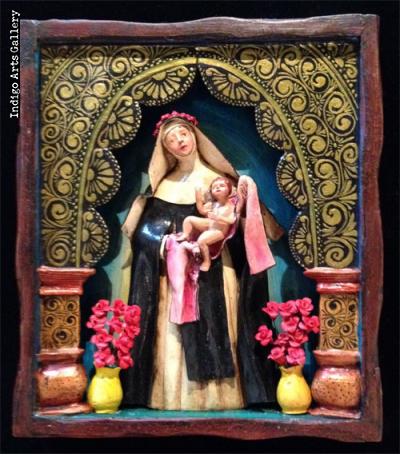

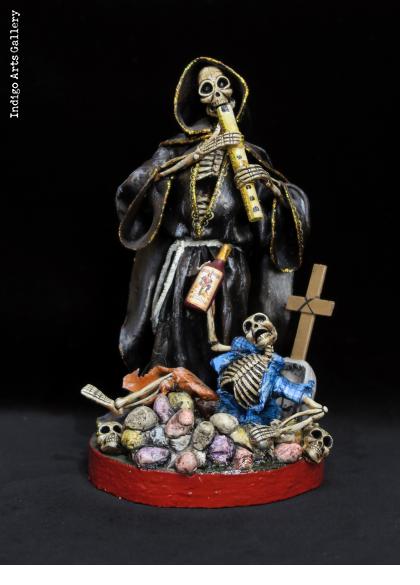

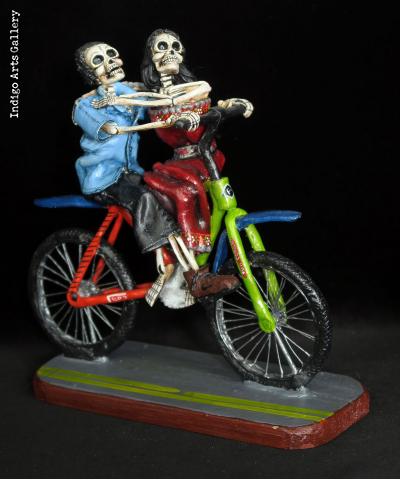

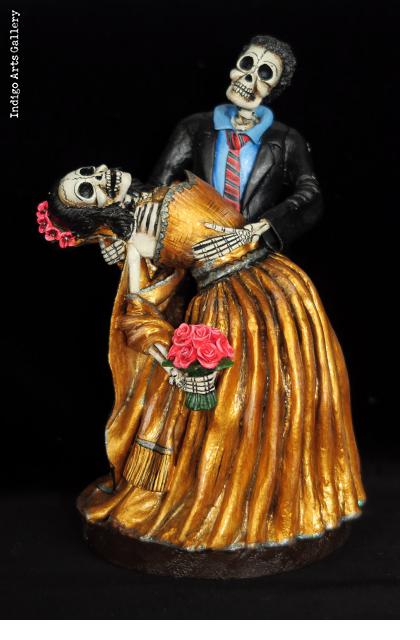

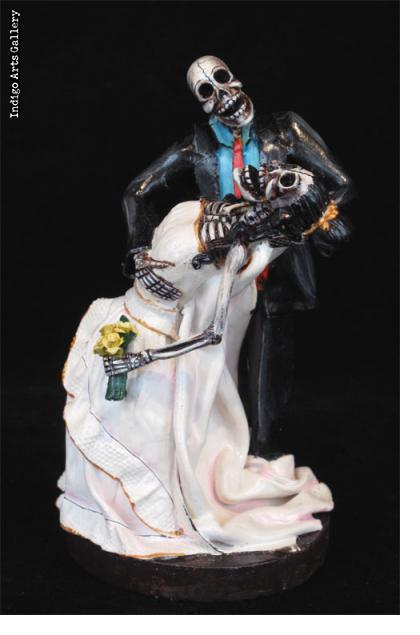

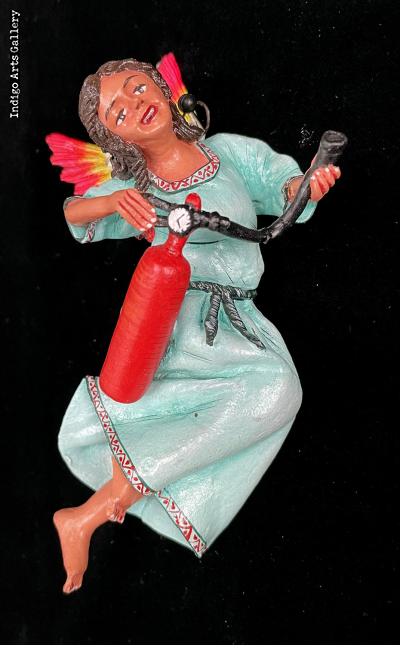

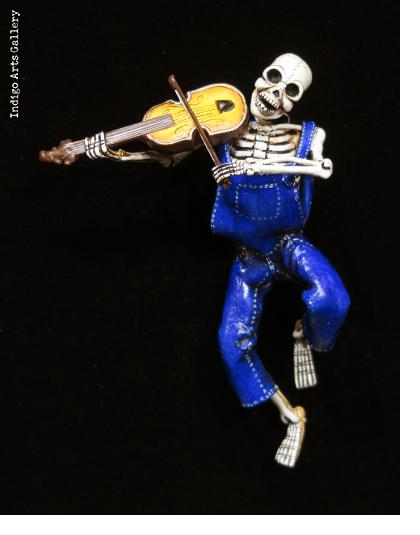

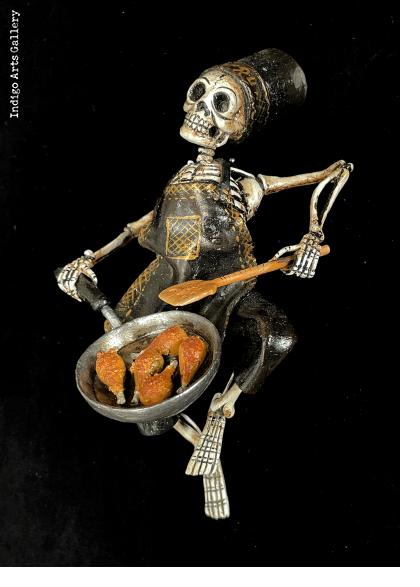

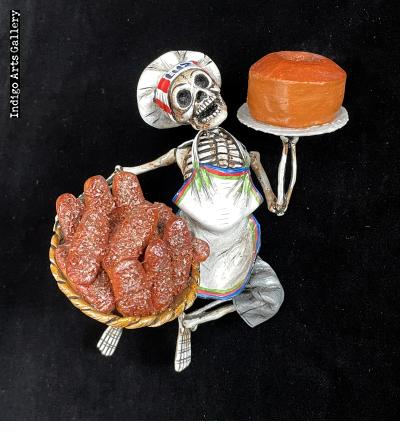

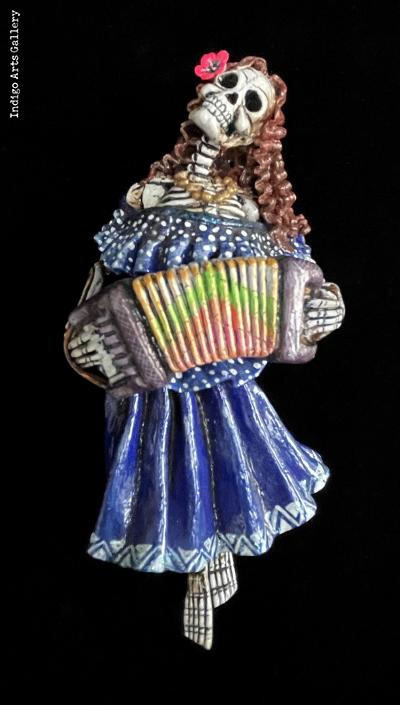

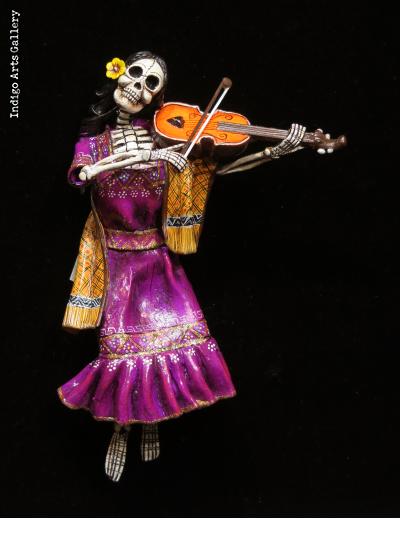

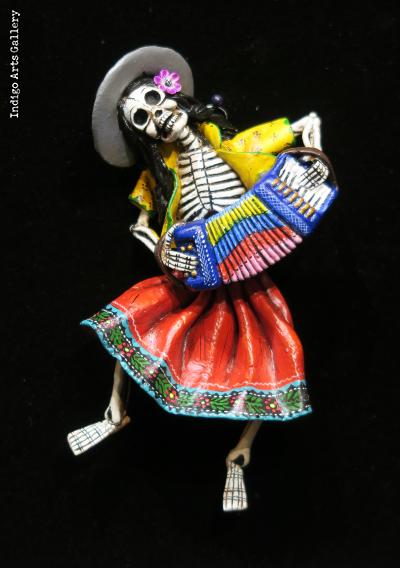

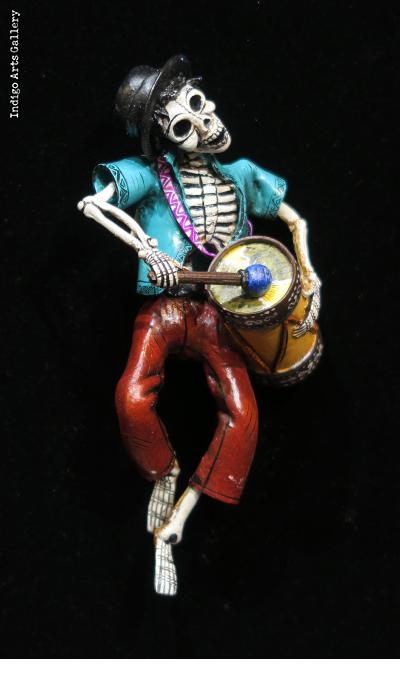

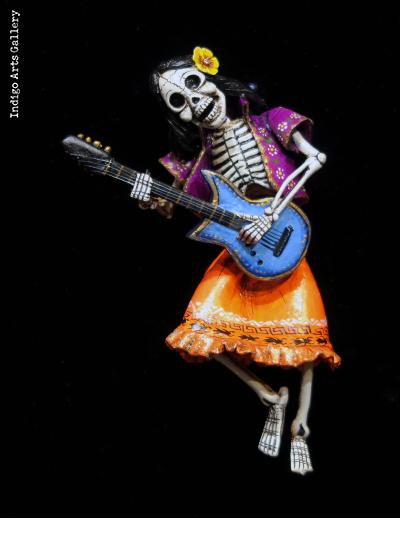

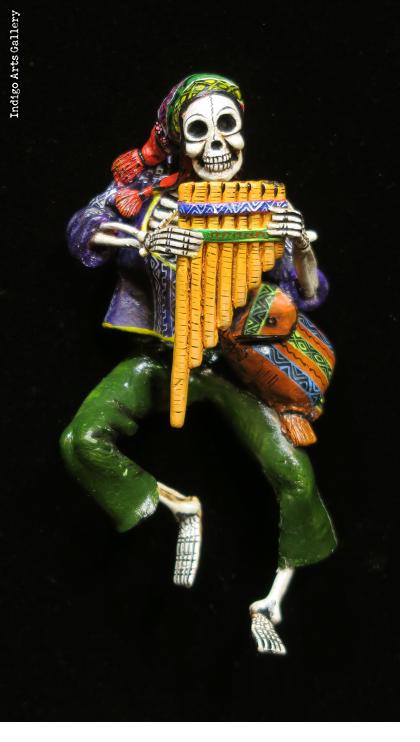

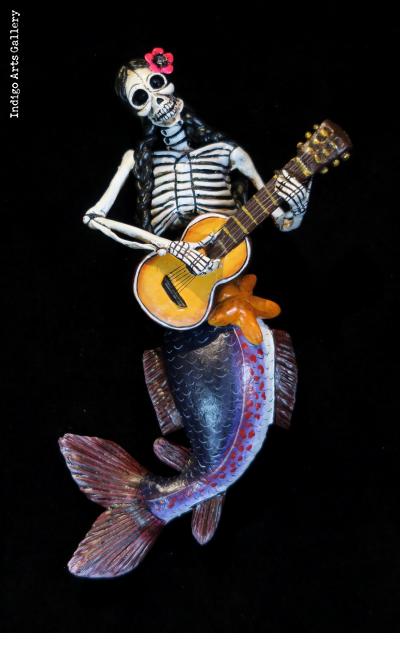

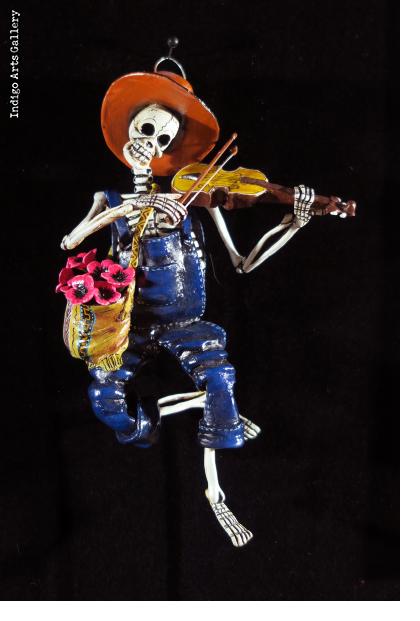

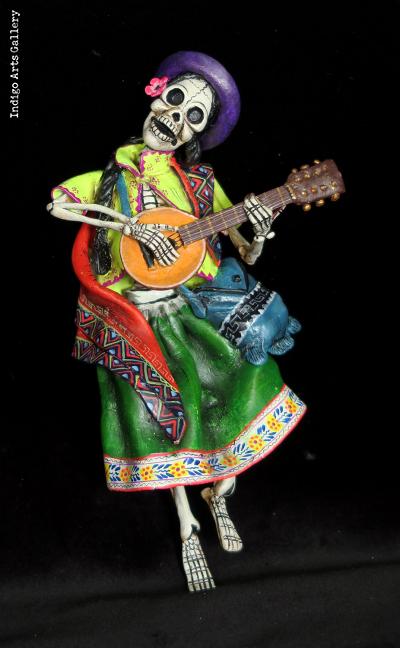

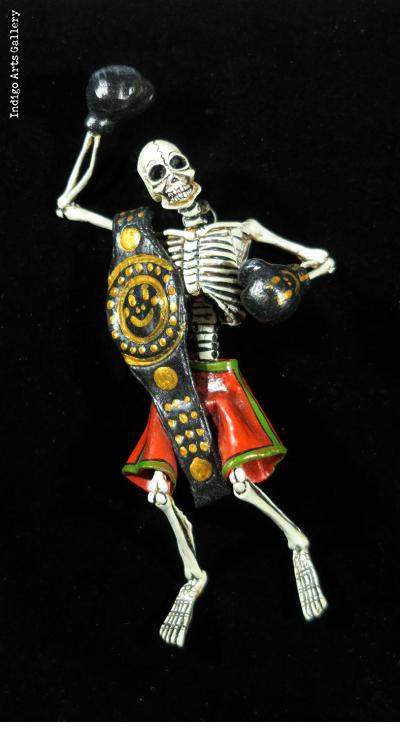

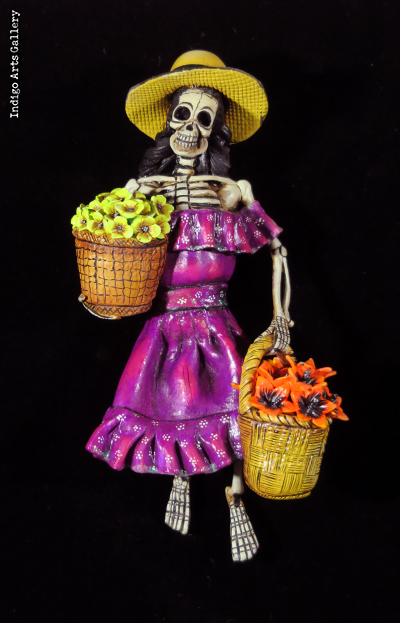

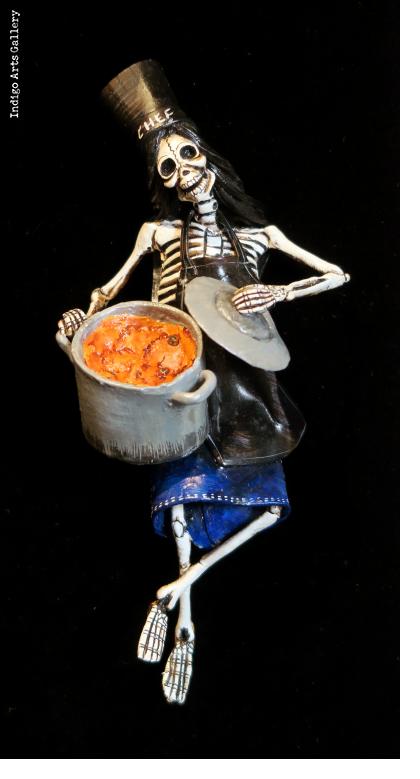

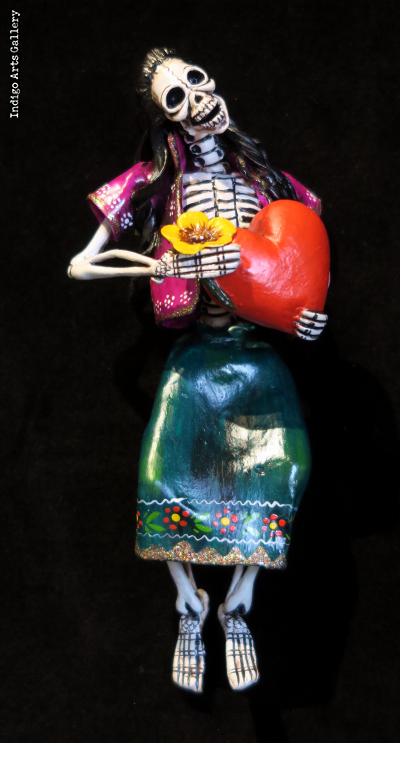

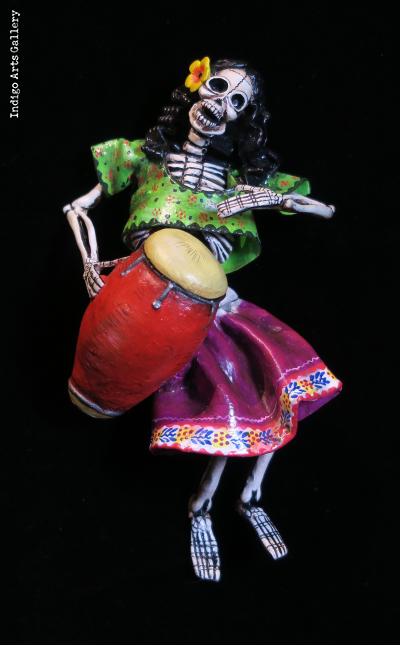

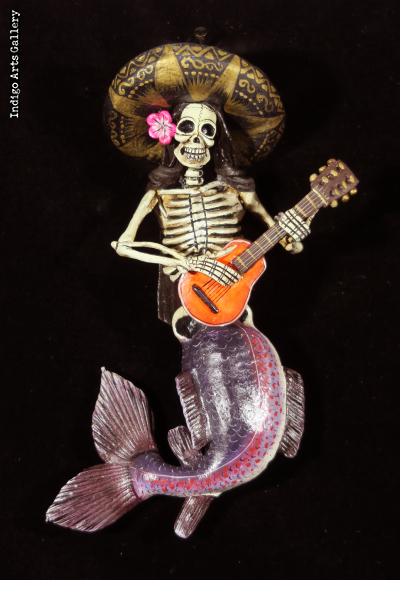

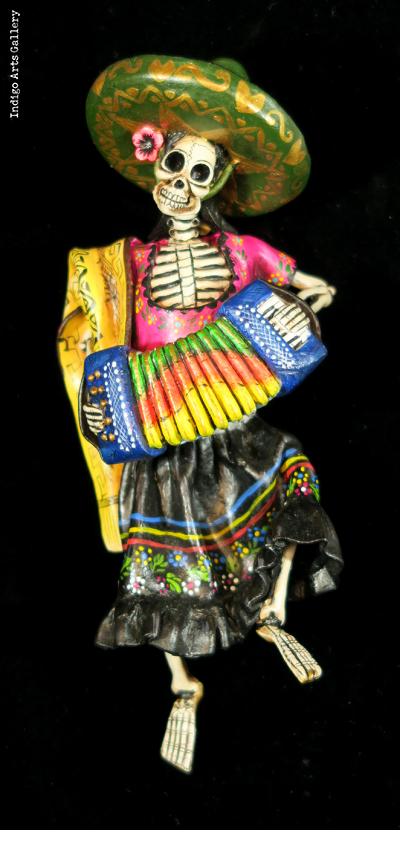

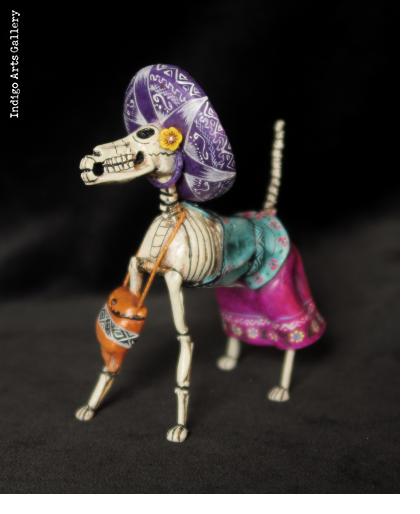

The current exhibit also includes examples of work by retablo artists from other parts of Peru, notably the Gonzalez family of Huanacayo. Javier and Pedro Gonzalez work in the style of retablo-making learned from their grandfather, Don Pedro Abilio Gonzalez Flores. The figures in the Gonzalez's retablos, as well as freestanding figures of saints and crosses, are carved of maguey cactus wood, which is then finished with a plaster gesso. Working in the tradition of Peruvian santeros, who carved saint figures for both churches and home altars, the Gonzalez brothers are known for the exquisite detail and sensitivity of their faces. like the Jimenez family of Ayacucho, they sculpt many figures of calaveras - skeletons - as well as more traditional subjects.